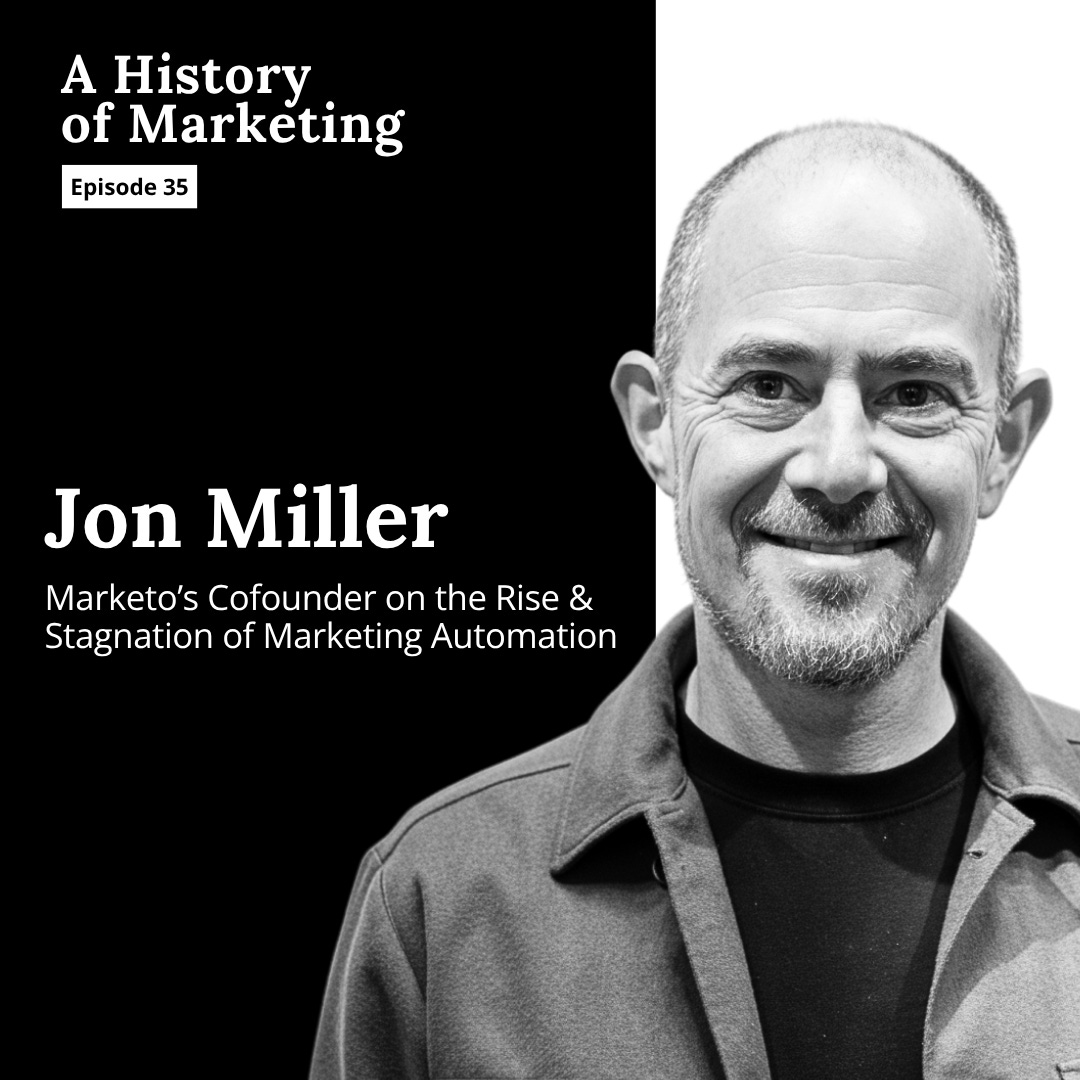

A History of Marketing / Episode 35

This week, I’m joined by Jon Miller, a Harvard-trained physicist turned marketing tech pioneer. Jon is best known as the cofounder of Marketo, and he helped define the playbook for B2B demand generation over the past 2 decades.

A serial entrepreneur, Jon founded Engagio and was CMO of Demandbase. He’s busy building his next venture (which he not-so-subtly hints at during our chat).

Jon pulls back the curtain on the rise of marketing automation. He shares the inside story of Marketo’s creation, the explosion of the “MQL-chasing playbook,” and how that playbook eventually led to the category’s stagnation.

This is a great companion piece to my last podcast episode with Kerry Cunningham. Together, they tell the story of the symbiotic relationship between advisory firms like SiriusDecisions and tech companies like Marketo. They created a powerful cycle: They sold B2B firms on new marketing frameworks, the software to manage them, and the consulting to implement it all, spiraling into what Cunningham describes as the “MQL industrial complex.”

Jon explains why he now believes the very system he helped build is flawed, leading to a focus on short-term metrics that “causes us to do wrong by the customer”. We discuss why he thinks innovation in the category “fell off a cliff” and what it will take to build a new playbook for the age of AI.

Jon is super insightful and a great storyteller, and he’s candid about the ups and downs of working with startups, so this one is entertaining and informative throughout.

Now here’s my conversation with Jon Miller.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Shoutout to Kerry Cunningham for introducing me to Jon Miller.

Thank you to Xiaoying Feng, a Marketing Ph.D. Candidate at Syracuse, who volunteers to review and edit transcripts for accuracy and clarity.

Andrew Mitrak: Jon Miller, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Jon Miller: Thank you for having me. Hello, hello.

Andrew Mitrak: I’m so excited for this conversation. I want to start with one of your LinkedIn posts. Quote: “The metrics-obsessed, MQL-chasing playbook that I helped create at Marketo is steering us away from marketing’s fundamental truth. Do right by the customer.”

And so, this quote encapsulates the story I’m hoping to unpack through this conversation with you: the creation of Marketo, how B2B marketing became obsessed with MQLs, and what sort of downstream impacts this had on marketing today. So, does that sound good to you?

Jon Miller: That sounds great. This is a topic near and dear to my heart.

Riding the Dot-Com Wave: MarTech in the Internet Bubble

Andrew Mitrak: Well, let’s start at the beginning. I saw that you started by studying physics at Harvard. So I’m wondering, how did you go from there to a career in marketing and MarTech?

Jon Miller: It’s one of those things that makes sense when you look at it retroactively, but you wouldn’t have necessarily thought it going in. I always thought I would be an academic when I studied physics, and I actually applied and got into MIT for a PhD program.

But at the same time, being at a place like Harvard, there’s a lot of recruiting, and consulting firms and banking firms who come to campus. I couldn’t help thinking that that life seemed kind of glamorous, potentially, compared to the life of the academic researcher. And so I decided to apply and give it a shot. MIT was kind enough to let me defer my admission for a year, and so I ended up taking a job in a management consulting firm. And it turns out I really liked it.

The quantitative background from physics actually applied to the consulting world, especially the kind of projects I was working on, which ended up being projects around topics like: there’s all this information about my customers, how can I use that information to make better decisions about how to interact with them and how to create the best value exchanges with them.

So, I decided to go to business school. And so I found myself at Stanford, from 1997 to 1999, which if you recall is like the peak of the internet bubble.

Andrew Mitrak: It’s an exciting place to be.

Jon Miller: If you were at Stanford and not thinking about starting a company at the time, you were doing something wrong. Almost by just momentum, I ended up getting a job at a company called Epiphany, which was literally down the street from Stanford. I started working there in my second year of my MBA, and I could literally walk there. That’s how close this was.

And I had no business getting a job in a high-tech company at that point. I had no high-tech experience or anything like that. But Epiphany was just entering the marketing technology space. Turns out, the consulting firm that I’d worked at before was a company called Exchange Partners, and we’d had a sister company called Exchange Applications. That company ended up building a marketing technology product that actually had an IPO and was probably the top marketing technology of the mid-90s.

So, Epiphany was entering that space. They knew about Exchange Applications as the competitor, and the fact that I had even any connection at all through this sister company was enough for them to give me a job. So I find myself at Epiphany at the peak of the internet bubble, building marketing technology.

The State of Marketing Technology in the Dot-Com Era

Andrew Mitrak: What did marketing technology look like at this time?

Jon Miller: It’s a great question. First off, it was on-premise. So, you know, half a million to a million-dollar software investment and another million-plus of implementation fees. And you were typically connecting this technology to a data warehouse. And it was mostly technology to build and extract lists. Right? So, The Gap would use Epiphany to query their data warehouse to pull this list for the direct mail catalog A versus this list for direct mail catalog B. And then email just started to come on board. So now they’re going to also use this to pull the list for email one and email two.

Andrew Mitrak: Who’s buying the technology? Is this an IT buyer? Is this a CMO who’s buying it? What’s who’s on the buying committee for something like this?

Jon Miller: Back then, with what I just described, it was like a million-dollar-plus investment. So it was complex capital investments that were very IT-driven. That was hard. The marketing department didn’t necessarily always have the political capital to drive their agenda into the IT department. And that was something that really, I think at the time, held marketing technology back.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, and I imagine that it’s just a brand new thing. That marketing technology is sort of a new category and that there must have been some customer education on your part for them to just buy a product and use a product and implement it through their org like that.

Jon Miller: To a degree. I think people had been doing—remember, especially before email, the main channel was direct mail, whether you’re sending postcards or coupon discounts or catalogs or things like that. And people had been doing direct mail and list pulls for a long time. It’s just they were doing it with handcrafted SQL code. And so, the innovation, the thing that was “new,” was the ability for a non-SQL database coder person to be able to go in and slice and dice the data to sort of start pulling some of their own lists. So it wasn’t a completely new thing, but it was a better, more efficient process.

Andrew Mitrak: So you’re at Epiphany in the dot-com era. Were they impacted by the dot-com bubble?

Jon Miller: Absolutely. I mean, I still remember the day that we announced that we had sold Amazon as one of our customers. And the stock went up literally, I’m not exaggerating, $70 per share that day. So I mean, that was literally hundreds of thousands of dollars of value on paper for me personally from that announcement. You can imagine that was a good day.

And then the internet bubble... we peaked at a market capitalization of $8 billion, which is just insane to think about. And then the internet bubble popped and everything came crashing down. The stock went from $300 a share down to $60 a share. That was still worth a fair amount of money on paper, but you can imagine psychologically, when it was just at $300, it’s pretty hard to sell it at $60.

And so, a lesson I learned is if you ever have the ability to take profit off the table, sell your stock when you can.

Founding Marketo and the Shift from On-Prem to SaaS

Andrew Mitrak: Can you tell me the story of founding Marketo? What was the problem you were hoping to solve with Marketo? This is sometime after the dot-com bubble bursting, I think it’s around the 2005 era. So what was going on then?

Jon Miller: I stuck with Epiphany until 2005 when we finally sold Epiphany to an ERP firm called SSA Global. And I didn’t have interest in working there. And so when I was offered a package to leave, I took the package, came home, told my wife this. She thought I was insane because we had just bought our first house and we had a mortgage and she was pregnant with our first kid.

So I was out kind of looking for a job, but I remember I had lunch one day with Phil Fernandez. Phil had been the president and chief operating officer of Epiphany. So I was like, “So what are you thinking of doing?” He’s like, “Oh, I want to be CEO of a company and I’m interviewing at a couple places, but I’m also thinking about starting something.” He asks me what am I thinking about doing. I was like, “Well, I want to be CMO or VP of Marketing and I’m interviewing a couple places, but it really does seem like there ought to be a company.” And we realized that the vision that we both sort of had for the company was pretty similar.

So what was that vision? To your question, like, what was the idea and what was it for Marketo? And I’ve already alluded to this slightly. So before Marketo, there was on-premise software, which was a complicated capital investment to buy. The problem is that most executives looked at marketing as a cost center, and it’s very hard to justify a capital investment into a cost center. People want to make it cheaper; they don’t want to make it better.

Andrew Mitrak: Right.

Jon Miller: And that really had always held marketing technology backward. And at the same time, in 2005, you had Google AdWords really starting to take off. Google AdWords only got up and running in 2002. And here was a thing that a marketer could buy programmatically on their credit card. And what we realized is that marketers have lots of discretionary budget, whether it’s to spend money on Google ads or a trade show or printing brochures. But the key idea is it’s all Opex, not Capex.

So the big idea from Marketo was that software as a service (SaaS), which was just becoming mainstream, could allow us to deliver complicated, serious marketing software as a subscription that a marketer could buy out of Opex and not Capex. So we had to make the software as easy to buy so they could make the decision of, “Do I do more Google ads, or do I buy Marketo?” And that’s what we really tried to build. Our mantra was “make it easy to buy, easy to own, and easy to use,” so that it would feel like that kind of Opex program investment. So that was the big idea.

Marketo vs. Eloqua: The Battle for a New Category

Andrew Mitrak: What were you kind of going up against with Marketo? You mentioned sort of on-prem technologies. If you were going to a big account that you were trying to land, what were you the alternative to?

Jon Miller: So there was this other company at the time called Eloqua. Eloqua started in 1999 as a chat solution, and I think in the 2003-2004 time frame, they started delivering what now became known as marketing automation. And it was technically SaaS, but it was sort of like a weird semi-SaaS solution, if you will.

Eloqua did a great job of convincing high-tech companies in Silicon Valley that they needed a solution like this. And we’ll talk about that more in just a second. But they also had a reputation of being complicated and expensive. And so it made for a really easy positioning for Marketo in the early days. Well, it’s like Eloqua, which you heard of, but that’s expensive and hard to use. We’re affordable and easy to use. That was the main thing we were positioning against.

Andrew Mitrak: The other thing that strikes me about Marketo compared with Eloqua is “Marketo” is a much better name.

Eloqua is kind of hard to spell, hard to pronounce, hard to know what it means, whereas if you’re selling to marketing and Marketo... it makes a lot of sense.

Do you remember coming up with that name, Marketo? Because it’s a pretty great name.

Jon Miller: Oh gosh, we tried all sorts of names and ideas. Even back then in 2005, 2006, getting a good domain was hard. So we would come up with ideas and I’d type it in, and nope, that one’s taken. Nope, that one’s taken.

Specifically, the story is, one day I was playing with anagrams of marketing and what not. I tried Marketo, and it was like, no, that’s taken. And then I tried Ramketo, where I just played with the letters a little bit, and I was like, “Ramketo.com, it’s available!” And I remember emailing Phil and saying, “Hey, what do you think of Ramketo?”

And he said, “Well, that’s terrible.”

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, it is. (laughs)

Jon Miller: He said, “What about Marketo?” And I was like, “It’s not available.” So then he just went to the browser and typed Marketo.com. And there it was taken, but the website said, “If you want to buy this domain, email me here.”

Andrew Mitrak: All right.

Jon Miller: So Phil emailed the guy and said, “I want to buy Marketo,” and $4,000 later, he bought Marketo.

Andrew Mitrak: Oh, man. Yeah, $4,000 in this day and age, that’s a steal. That’s great.

Jon Miller: Yeah, exactly. So that was how we ended up being Marketo.com.

Andrew Mitrak: I always love company naming stories and getting domain stories because there’s always some little hustle to getting the domain.

Jon Miller: Yeah, exactly.

How Marketing Tech + Marketing Consultants Sold “The Demand Waterfall”

Andrew Mitrak: So, one of the things that is associated with Marketo is this idea of the marketing qualified lead, or the MQL. Do you remember the first time you ever heard the phrase “marketing qualified lead?”

Jon Miller: I think so. So the term was coined and popularized by SiriusDecisions, which was an analyst firm. And they published what they called the Demand Waterfall. And so what they had was MQL, they also had the SQL (Sales Qualified Lead) and the SAL (Sales Accepted Lead). I believe they debuted that formally in 2006, which was the year that Marketo got up and running.

I think in the early days, a couple of things kind of came together. One, Eloqua and SiriusDecisions kind of had a little bit of a symbiotic relationship, where SiriusDecisions was saying, “Hey, you should follow the Demand Waterfall.” Well, people would be like, “How do you do it?” They’re like, “Well, you need Eloqua to do it.” And Eloqua would be on the reverse side of that thing, like, “Hey, you should follow the SiriusDecisions model.” And so that synergy behind the MQL and the Demand Waterfall is part of what drove that Eloqua success, especially in those venture-backed tech companies.

Andrew Mitrak: Right.

Jon Miller: And that’s what we were able to glom onto with Marketo, as like, “Oh, you want to do this MQL thing that you’re hearing about from SiriusDecisions? Well, we’ll make it easier and more affordable for you to do that.”

It was related to the core ideas of lead nurturing and lead scoring. Because the other thing you have to remember that was happening at this time is Google AdWords and other digital marketing channels were just beginning to take off. It was literally still early days where somebody might click on an ad and come to your website and fill out a form. And you needed a place to put that lead, if you will. But people realized that just because that person filled out the form, they weren’t necessarily ready to talk to a salesperson. It was a waste of time for both sides. So you needed technology to help you keep in touch with that lead and nurture it and develop it till it was ready. And you needed some ability to score them to know when they might be ready and it’s time to pass them.

So by 2008, 2009, people were basically like, “I gotta get me some lead nurturing!” Like literally, that’s what people would say on their first call with us. They’re like, “Apparently, I have to do lead nurturing and you can sell me lead nurturing, so how fast can I get started?” And that’s kind of what drove a lot of the success in the early days.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, it’s funny because I had spoken with Kerry Cunningham, who was at SiriusDecisions at one point in time. And when I was asking him about the origins of MQL, he was kind of blaming the marketing tech. He was saying the marketing tech came first, but it wasn’t totally clear to me. It seemed like a little bit of a chicken-or-the-egg-type thing.

Jon Miller: I think it was very much a symbiotic thing going on.

Andrew Mitrak: They’re working together in cahoots with each other.

How Marketo Built the MQL-Chasing Playbook

Andrew Mitrak: You alluded to this right at the start: “the MQL-chasing playbook that steers us away from marketing’s fundamental truth: do right by the customer.” And you mentioned that Marketo is partially responsible for this MQL-chasing playbook, and people were coming to you saying, “I want to nurture some leads.” Why is that? What was Marketo’s share and responsibility in popularizing this sort of MQL-chasing playbook?

Jon Miller: I literally wrote a book at Marketo called The Definitive Guide to Lead Nurturing. I wrote another one called The Definitive Guide to Lead Scoring. And so I went on teaching people, “This is how you do these things.”

Over time, we became known as this successful, fast-growing company. And people would ask me to come give presentations about how you do it. Like, “Tell me, how do you do it? What is your secret sauce for your fast growth?” Right? And so I would give presentations on how I generated my leads and how I would nurture them and how I would score them and create the MQLs and pass them along. And it just almost created... it became this playbook that if you’re a tech company looking to grow, this is kind of how you did it. And again, it wasn’t just me. It was also SiriusDecisions preaching things, and it was also Eloqua preaching things and the rest of the category. But collectively, we created a movement where the MQL became the holy grail that everybody was trying to achieve. It became the standard of success for marketing.

Andrew Mitrak: The MQL industrial complex is what Kerry had called it.

Jon Miller: Yeah.

Finding Traction and Product-Market Fit

Andrew Mitrak: So, you’re talking about Marketo gaining traction, and I want to dive into this story because it was founded, you said it launched in 2006, you co-founded it in 2005. Was it immediate overnight success, or when did you feel like, “Hey, this is a company here?”

Jon Miller: I skipped a little part of the history of Marketo, which was the very first product we built was to help manage your Google AdWords. So it could set your bids and it could make your ads for you and A/B test the ads and also host landing pages to capture the leads. And it was easy to buy it. Come to the website, free trial, give me your credit card, start using it. And that product did not have great traction for a variety of reasons that we probably don’t have time to totally get into. It was too easy to buy, if I sort of oversimplify it.

But we always knew that pay-per-click was just one step along the way, and we were going to add email and automation and these other things. So what’s interesting is we were building the thing that became marketing automation. And that didn’t actually come out till 2008. But as we were beta testing that and approaching it and getting ready to build it, it was clear that people thought there was something special there. Like people who knew Eloqua would look at what we had and they would say, “Wow, that is really cool and easier.”

And Phil made a really interesting decision that was the right decision, but I always wonder if I would have made it myself, which is he decided to kill the pay-per-click product. He was like, it’s just not successful enough, it’s distracting - even though we worked on it for a while - it’s distracting from this other thing that seems like it’s a success. He also changed out our head of sales not long after the launch of the marketing automation product.

These two things kind of made it come together. We had this product that seemed to have product-market fit and traction, and now I had a counterpart in sales who was executing well against the leads I was creating. So by mid-2008, it felt like we were starting to really hum along with traction.

From PPC to a Full Platform: Finding Marketo’s True Calling

Andrew Mitrak: Between these two products, the pay-per-click one and the marketing automation one, was there a different buyer for these products? And I’m also wondering, you were mentioning how with Epiphany, because it was a big upfront Capex versus Opex, that this was a different selling method as well. So were these marketers directly could buy it versus IT? Who was actually buying this at the company?

Jon Miller: The pay-per-click (PPC) product would have been purchased by the digital ad manager. So literally the same person who would otherwise be logging into Google and setting keyword bids, they could just kind of buy our tool. The biggest problem there is, at the end of the day, we were a better UI on top of Google. But it’s really hard to compete against Google’s UI, right? They keep changing and evolving and adding things, and it was a challenging product.

The marketing automation product, because it got wrapped up into this MQL, lead nurturing, lead scoring thing, it started to have more CMO-level visibility. And so the buyer was either the CMO or the head of demand gen or something like that. So it was a more senior, more strategic buyer. But in most cases, it was not IT.

Andrew Mitrak: It was not IT. It was a marketer, and it was sort of higher in the org chart. It’s a little more lock-in as well.

Jon Miller: Yeah.

The Marketo IPO Experience: Marketing Automation Goes Public

Andrew Mitrak: So Marketo IPO’d in 2013, and there aren’t that many marketing technology companies that I can think of that are publicly traded.

Jon Miller: There aren’t that many.

Andrew Mitrak: There just aren’t. It seems like this is just an exciting experience to have co-founded a company and to IPO, and I’m just wondering if you have any sort of favorite stories from this IPO era.

Jon Miller: We IPO’d on Nasdaq. Nasdaq doesn’t have an official trading floor like the New York Stock Exchange. So at the New York Stock Exchange, if you IPO, you get up on the big podium, you literally ring the bell, and that opens up the trading. But in Nasdaq, they have this fake studio where you press a button and confetti drops down, but it’s just a digital exchange. So, besides the confetti dropping, nothing actually happens.

And the other thing about Nasdaq is they don’t immediately start trading the stock. Instead, there’s this whole process where they kind of clear the buy and the sell offers to figure out what the opening price is going to be, and then the stock starts to trade digitally. And that can take like an hour, an hour and a half.

So we go to the IPO ceremony, we have our picture up on Times Square, there’s the big celebration, the button, the confetti. But you remember this is all like 9:30 AM, which is 6:30 AM my body time. And we’ve been going out the night before. And then we go to another room where they give you a glass of champagne. And then all of a sudden, all the adrenaline just leaves your system. Right? Because you’re exciting and champagne, and now you’re just sitting there for an hour and a half waiting for things to happen. And I literally fell asleep on the table from the adrenaline drop.

Andrew Mitrak: Wouldn’t you be so... have a lot of adrenaline just to see what happens? In that hour and a half, wouldn’t you have a ton of anticipation? Like, is it going to go up? Is it going to go down? Like what’s going to happen? Did I leave money on the table? Is it going to pop?

Jon Miller: I very much wanted to see it, but nothing’s happening. You’re just literally sitting there waiting in a room. And so the buzzkill and the energy drop of it is what I’m sharing, for what it’s worth. It’s a first-class problem, I understand.

A Cautionary Tale: The Post-IPO “Why”

Jon Miller: The other story I’ll share is more of a cautionary tale, which is, as we approached the IPO, that in some ways almost became the reason why we existed. Right? Like, “We’re successful, we’re going to IPO,” and “Why should you join Marketo? Because we’re going to IPO.” Culturally, that became our “why,” in the Simon Sinek viewpoint. And that’s a terrible why, because then once we IPO’d, everyone was like, “Okay, now what? Now, why do we exist?”

And I don’t think Phil and I did a very good job defining the culture to be something more meaningful post that. So, you know, it’s a lesson that the IPO is just a financing event at the end of the day, and you need to have a “why” that’s deeper than just, “We’re successful.”

Andrew Mitrak: You left Marketo a couple of years after the IPO.

Jon Miller: Yeah, I left in 2015.

Andrew Mitrak: In 2015. And then a couple of years, a few years later, Adobe acquired Marketo. Do you have any reflections on what this meant at a high level for marketing automation to be acquired by Adobe? Was it a significant milestone?

Jon Miller: Yeah, I think the trend was very significant because there were really four major players that ended up making up the marketing automation space. You had Eloqua, which by this point had been acquired by Oracle. You had Pardot, which had been acquired by ExactTarget, which got acquired by Salesforce. Right? And now you had Marketo being acquired by Adobe.

So three of the four major players were now acquired, with HubSpot being the only real standalone player. But even then, HubSpot, you know, pivoted away from just marketing automation to be CRM and kind of this full platform suite. So if you look at it across the board, I think starting in around 2018, you saw innovation in the category fall off a cliff. You can go look at Marketo today, and it looks like it did in 2018. Right? Yeah, there’s been a couple of bells and whistles added, but it’s still fundamentally pretty much the same product. And so I think that that has been a major disservice to the category, that there’s been so little innovation in the last six, seven years.

And yet, buying has completely transformed in that time frame. And then AI comes along and it’s changing it even again. I personally think the current marketing automation category is incredibly stagnant, and there needs to be a new modern alternative, and somebody needs to build that. Hint, hint.

Unpacking the Anti-MQL Manifesto

Andrew Mitrak: Right, right. So let’s just also reflect on some of the things we sort of alluded to as well, is that you’d co-signed this Anti-MQL Manifesto with Kerry Cunningham, who I mentioned I’d also interviewed for this podcast. And you’re not a fan of MQLs today. And I’m wondering, when did you first get an inkling that something was off with this model? Was it while you were at Marketo? Was it some time after?

Jon Miller: I mean, it started when I was at Engagio, which was the company I started after Marketo. And Engagio was what’s known as an account-based marketing platform. The whole idea of account-based anything is that in B2B, leads don’t buy things, companies buy things. And just because a person from a company comes to your website and fills out a form doesn’t necessarily show any indication that that company is looking to make a purchase. Similarly, you could have 10 people from a company show up on your website to do some research, but none of them fills out a form. That wouldn’t generate a single MQL, but it would certainly show that there’s something happening at that company that’s maybe worth identifying and following up on. So the problem with the lead-centric view started back in my Engagio days.

But fast forward to say 2023 or so, this is when I really started writing about it more. As a marketer—I mean, at that time I was the CMO of Demandbase. Demandbase had acquired Engagio, I was running marketing for Demandbase. And I’m doing marketing, I’m doing the same secret sauce playbook that I did back at Marketo, the exact same stuff that worked so well at Marketo, and it’s just not working as well. It got me thinking, like, what’s going on here?

And I started realizing that the buyer has gotten really frustrated with a lot of the tactics that we’re doing. I started thinking about the fact that the MQL model ends up being a very, I think, transactional way of thinking about marketing. It teaches us, or it makes us think, if I need more MQLs, I just need to run more campaigns. But as I like to say, marketing is not a gumball machine. That’s not how buying works, where you can just put more quarters in and get more stuff out.

In fact, I think a better model for buying is a complex nonlinear system, which I studied back in physics. Like the weather is a complex nonlinear system, the stock market is a complex nonlinear system. And if you’ve ever heard of chaos theory, that’s all about studying complex nonlinear systems. Most people have heard of the butterfly effect, which is the sensitive dependence upon initial conditions that comes out of chaos theory on nonlinear systems, which is one small change here can have unpredictable effects there. That applies to buying. And if you embrace the fact that that’s how buying is working, trying to ever say, “Oh, well, I ran this one campaign which caused them to fill out that one form, which became a lead, which became a deal,” is just naive thinking.

And then second, I think that the MQL way of thinking causes what I call the tragedy of the commons. Which is, anytime a tactic works, people will just keep doing more of that tactic until that tactic no longer works.

Andrew Mitrak: Right.

Jon Miller: And we see that in social, we see that in content, we see that in email marketing, and GenAI is only making that problem worse because it’s easier than ever to create more of all these things.

But I think the worst thing about the MQL mindset is that it encourages short-term thinking. It’s like, I need this many MQLs to make this many deals, opportunities to make this much revenue for this quarter. It’s all about, what am I doing this quarter? And if I don’t have enough MQLs this quarter, what am I going to do? I’m going to do more stuff, causing more tragedy of the commons, causing people to tune out even more.

If we need more MQLs, what do you do? You’re like, “Well, let’s gate our... let’s gate things and put stuff behind forms so that way they’ll have to fill it out to get our stuff so we get more MQLs.” But that actually hurts the buyer experience. Increasingly, we need to be thinking about things like brand and how people think about us before they ever fill out our form. But you don’t do those investments if you’re trying to drive MQLs. So all these things work together to sort of come back to that point that I said, which is it causes us to do wrong by the customer. And that’s why I signed the manifesto, because I think we need to change.

Andrew Mitrak: Exactly. Yes. Well, preach. Amen to all of that. Everything rings true. This idea that it’s transactional, and I’m wondering if at some point the transaction kind of worked and then customers kind of caught on. Basically, I make The Ultimate Guide to X, it’s some PDF, it’s behind a form, you fill it out, and we kind of agree transactionally: you fill this out, you get your PDF, and I send you a bunch of emails you don’t really want that much.

And maybe for the marketer, in the aggregate, that download plus their other behaviors indicates some signal that they might actually be interested in our product and might be a sales-accepted lead down the line. At some point though, the buyer catches on, “That ultimate guide to whatever is probably not worth all the emails I have to unsubscribe to, and it’s just not worth the hassle, and I’m not going to click anymore. I’m just not going to do that.”

What I’m wondering is, did it ever work? Is it that it worked at one point and it was novel enough and it was low-cost enough that it wasn’t so saturated that it did work? Or was it doomed to fail from the start?

Jon Miller: Yeah, I think it’s a little bit of both. You know, so, as I said, it did work at Marketo. You know, and people did download The Definitive Guides, and I think they did get value from them because they told me they got value from them. And then you fast forward to my time at Demandbase, and I wrote the best book I’ve ever written there, and it was hard to get people to download it because I think the world had sort of, for lack of a better word, gotten saturated and moved on.

So yes, I do think there was that... there’s an arc to all these kinds of tactics at play. But I think what the MQL model never got right is that it always had this sort of short-term focus and a bias towards doing things that were measurable, even if they weren’t the things that would be the right long-term strategies. Most classically, over-investing in conversion performance marketing and under-investing in brand marketing.

So I think that’s just fundamental to the problem.

The Future Playbook: “True Revenue Marketing” and Shaping Perceptions

Andrew Mitrak: You kind of had hinted at this—you literally said “hint hint” - as far as what you’re working on now, what we can do to sort of find a better path to the future. Can you share more about the work you’re you’re doing now and what you think sort of the vision for the future of marketing is, kind of given this history?

Jon Miller: Not much more than the “hint hint,” I think, because we are kind of still in stealth. But, you know, at the highest level, as I’ve alluded to, the current category is stagnating. It is not evolving for the age of AI, it’s not evolving to the new playbook. And there really ought to be an alternative that people can go to when they’re looking for something that’s easier and more intelligent.

Andrew Mitrak: Well, we all look forward to some announcement or some product or some company in the future that solves all these problems. Also, just reflecting on this conversation, are there any other top-of-mind lessons for listeners that come to mind as far as this history of MQLs, the history of Marketo, and everything that we’ve talked about today? What are some of, like, if you were to sum up some of the top takeaways, what would those be?

Jon Miller: I would start by saying, okay, it’s clear that we need to act differently, and that there is a new playbook that needs to focus on what I would call “true revenue marketing.” Right? Which is not “how many MQLs can I create,” but “am I shaping market perceptions so I’m the first one a buyer contacts when they actually are ready to buy?” That has positioning that’s so compelling that the competition reacts to us. And that has such strong brand preference that we don’t need to discount to win the deals. So these are some of the aspects of the new playbook.

I really do believe that the pendulum in marketing needs to shift back a little bit more towards focusing on some of those fundamentals, if you will. So that’s one of the takeaways, but I don’t want anybody to walk away listening to this podcast thinking any of that’s going to be easy.

Andrew Mitrak: MQL calculations: “I spend this much on this channel and get this many MQLs that convert at this rate,” is kind of easy. There is a formula that’s been figured out. The problem is often, it ends up being ROI negative if you calculate it all the way down, and so you can’t keep doing that.

Jon Miller: Again, the problem with the sort of simple waterfall math is that it’s just... it doesn’t match reality.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, that’s exactly right.

Jon Miller: A model is great to the extent that it’s useful, but if it doesn’t actually reflect the way the world works, it’s going to cause you to make the wrong decisions. But the problem is, I and others spent 15 years teaching CFOs and investors and CEOs that the MQL model is the way that you’re supposed to do things. And so you have PE firms now and VCs who expect MQLs and “how many MQLs are you going to get?” and “what’s your cost per MQL?” and all that kind of stuff. And so as a marketer, if you come in and just say, “Oh, we’re not doing any of that anymore,” it’s not necessarily as easy as saying that.

And so, you know, we could have a whole other podcast on how do we evolve this conversation? Like, how should a marketer evolve the internal organization? How should they position an investment in brand in a way that doesn’t sound squishy-squishy? How do they recruit the head of sales and the head of customer success and other members of the leadership team to tell the story? Because if it’s just the CMO complaining, then it’s marketing complaining. But if the whole revenue team is complaining, then it’s a business problem. That kind of thing. So it’s not easy, but it is also important.

Andrew Mitrak: No, that’s totally right. And if you have any pointers on how to do that, I’m certainly all ears. Maybe we can bring you back for round two of a podcast to have that conversation. In the meantime, Jon Miller, I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. Just as a final question, where can listeners find you online and learn more about your work?

Jon Miller: The best way is to follow me on LinkedIn. I share my thought leadership, my ideas, my best practices there. Also, cocktail recipes for anybody who is interested in trying to see what cocktails can teach us about B2B go-to-market. That’s by far the best way to find me. I also have my website, jonmiller.com.

Andrew Mitrak: I’ll link to both of those on the blog that accompanies this post. So, Jon Miller, thanks so much for joining me. I really enjoyed it.

Jon Miller: Thanks for having me.