A History of Marketing / Episode 34

Today we’re talking about a phenomenon my guest, Kerry Cunningham, calls the “MQL Industrial Complex.”

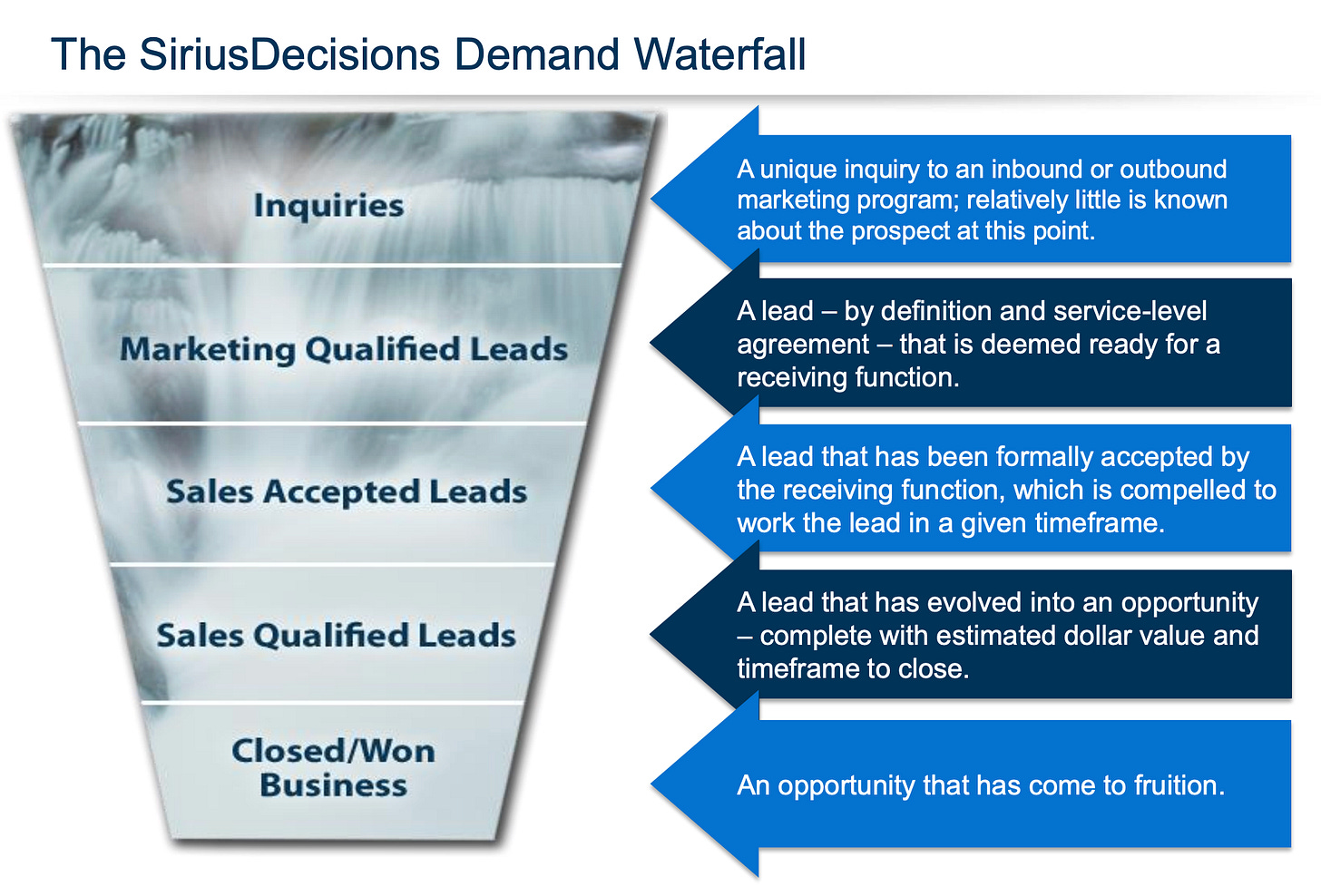

If you’re not in B2B marketing, that term might be new. It refers to the Demand Waterfall, a framework introduced has dominated business-to-business marketing for two decades.

It’s shaped how companies organize their teams, spend their budgets, and ultimately, measure success. It introduced the phrase MQL (marketing qualified lead) and standardized SQL (Sales Qualified Lead).

Kerry Cunningham is among the world’s foremost experts on this topic. He was a Senior Research Director at SiriusDecisions, the company that invented the Demand Waterfall in 2006. He was also a VP at Forrester, the company that owns it now.

And here’s the twist: Kerry is now one of the Demand Waterfall’s staunchest critics, arguing it was misguided from the beginning. He’s now Head of Research and Thought Leadership at 6Sense and is exploring what comes after the MQL.

As a B2B marketer who’s spent a lot of time working within this model, I tend to agree with Cunningham’s arguments. This conversation gets to the heart of some of the bad incentives and flawed assumptions I’ve seen firsthand, so you might hear me get more fired up than usual in this one.

Even if you’re not in the world of B2B marketing, this episode is a great case study in how marketing theory, practice, and technology all intersect to shape the industry.

Now, here’s my conversation with Kerry Cunningham.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Thank you to Xiaoying Feng, a Marketing Ph.D. Candidate at Syracuse, who volunteers to review and edit transcripts for accuracy and clarity.

Andrew Mitrak: Kerry Cunningham, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Kerry Cunningham: Thanks, Andrew. I’m glad to be here.

Andrew Mitrak: I’m excited to have you because I first encountered your work from The Anti-MQL Manifesto and your description of The MQL Industrial Complex. MQLs have existed as long as I’ve been in B2B marketing, and they’re something I kind of live with, for better or for worse—probably mostly for worse—throughout my day. And so, transparently, I think they’re the wrong metric and lead to a massive waste of time and effort. So your content around this resonated with me.

But part of this podcast, since it’s a history podcast, I’m always curious about, “How did we come up with these ideas? Where did MQLs come from? How did we start living in this MQL industrial complex?” So, can you describe for listeners, where did this MQL industrial complex come from?

The Genesis of “The MQL Industrial Complex”

Kerry Cunningham: Totally, yeah, I’m happy to talk about that. And I think it’s important to understand the history because one of the things that I’ve been doing really constantly over the last seven or eight years is telling everybody we’ve been doing it wrong. And that message is not always well-received, curiously enough. But what I find is if there’s an understanding of how we got here, then it can help ease the pain of realizing that we got to move on.

So how we got here, I think, is kind of just a fluke of technology in a way. My friend Jon Miller, who started Marketo, or one of the founders of Marketo, and a few other folks—the founder of Eloqua. I almost started working for one of the very first marketing automation platforms back in the late 90s also.

Those systems were designed primarily with the idea of the buyer as a person in mind. And certainly, the simplest way to have a system that is going to try to engage people and then try to collect and do something with that information is one based on individual people.

The buyer in B2B has never been an individual person, except on the very low end of the scale. But, you know, we find even now, if the deal is a $50,000 annual value or more, which is not a particularly big deal in B2B, there’s five or six people involved in that not just the decision-making process, but all the researching process.

So anyway, the first technology that came around was built around the person because that was the easiest object to focus on. And what happens over time is you get these systems, it was widely adopted and very rapidly. And then once that happens, then things come along like—I worked at SiriusDecisions for a long time. SiriusDecisions developed the really canonical framework for measuring how you’re doing in this world where you’re producing leads.

And so, SiriusDecisions developed the framework, it became a standard, and so you’ve got these practices: “Oh, let’s go out and get some leads, that seems like a thing that we do. Okay, great.” Now we’ve got a framework for saying, “Here’s how we should measure it.” Then you get standards, you get benchmarks are developed, and everybody wants to know, how am I doing? What are the best practices for improving that?

And before long—and this is why I call it a complex, because it isn’t just the technology. It’s the technology plus you get these measurement frameworks, you get standards, you get benchmarks. And all of those things get an entire industry focused on how to improve their execution of the process, rather than asking the question, should we be doing this at all? Because if anybody had been asking the question, “Should we be doing this this way at all?” 20 years ago, the answer would have been, “No, this doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

But instead, what happens is you get some technology, it’s the first thing everybody has. You want to use it. How does it work? Well, we send emails to people and they respond. They come to our website, they fill out a form, and we go after them. Okay, well, we can do that. Who’s doing that well? What’s the best process for doing that, right? So it all just goes down that path of, how do we do it well, or how do we execute best against this, instead of really thinking about whether we should be doing it.

And the curious thing is, in those same organizations, and I was in some of them back in the day, you have people in product marketing, content marketing, even when it was new, thinking about buyer personas and understanding that each account that they might want to sell to has multiple buyer personas. But nobody ever connected the dots between, “Well, what happens if we get multiple buyer personas who happen to respond to this stuff we’re putting out there?” Is that a thing we should notice? Should we care about that? Does it matter? Is it good? Is it bad? That question, I mean, like literally never got asked. And when you look back, it’s like, well, that’s the simplest, dumbest thing in the world we should have been doing.

So that’s really kind of how it goes. It’s kind of this first-through-the-gate with the technology, and then everybody went after it.

How Marketing Automation Software Shaped the MQL

Andrew Mitrak: That’s a great high-level overview and framework for how it developed. You know, just kind of diving deeper into that, when that technology developed—it sounds like the technology developing, the first marketing automation platforms that were adopted—that kind of helped set some of the groundwork for this industrial complex to be built upon. What were those technologies specifically, and around what years did they come out and start to get adopted?

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, so the marketing automation platforms. And so, Marketo wasn’t the first, but it was certainly the first really widely adopted, really well-marketed. And it functioned very well for what it did. Eloqua came along more or less at the same time. So this is the mid-2000s, 2005, 6, I think, in that time frame when these things come around.

A lucky coincidence for me, in a sense, is that—and actually, I think I would take that back and say it’s probably more like 2007, 8, 9 when it really started taking hold. The technologies were around since 2004 or 5. I dropped out of B2B. So I was part of a company, and we had a liquidity event, and I just dropped out of B2B for about four years. The four years when marketing automation was really coming in and taking over. So I left B2B, I did other things, I came back, and I was able to look around because I wasn’t part of the implementations of all of this. I didn’t get caught up in the “how do we do it better?” I came around and I looked at it and I was like, “What the hell is this? This doesn’t make any sense.” The buyer is this big group of people, and all you’re doing is looking at individuals and not even noticing if we have buying committees, whatever, paying attention.

So that’s really when it happened and also why I was just fortunate. Like, if I had been working in the space in that time, I’m sure I would have fallen into the same trap as everybody else. I’m not any smarter than anybody else in that respect.

Andrew Mitrak: And so these technologies come out, and they look at leads as an individual person versus being structured to look at somebody as like a team—that teams or groups of people purchase products. Was that a technology limitation at the time as to how these were built? Or was it more of just the initial idea? Because if there were some flaws to them, I’m wondering why they got adopted. Was it a technical reason at the time? Was it just that, “This is better than before, and don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good”? What do you think it was that led them to get so adopted at this point?

Kerry Cunningham: A little bit of a mix of those things. So I think one, the technology is easier if you don’t have to connect disparate individuals from the same organization. That’s a complex problem to solve. And you’ve got examples from B2C where they already have systems like this where we’re tracking individual people in B2C contexts. So you can just port that idea over, which is really what happened, to B2B. So it was kind of a borrowing from B2C, where the buyer really is an individual most of the time, into the B2B context.

And then, frankly, I think just what we do as humans, which is we fall in love with the technology, and we’ve got a new toy, and we’ve got a new thing, and we don’t think that deeply about whether it really is the right fit all the time. It’s just, it’s exciting to have it.

And I was around at the time before this happened. And before this happened, you’ve got outbound prospecting, and you’ve really got no inbound marketing the way we came to think about it. You get very few leads of any kind. Mostly, it’s just you have to find companies and go out and prospect into them. So I wouldn’t want to underestimate how exciting it is as, one, as a marketer to finally be involved in revenue, because frankly, before that, you’re not. Right? If you’re a marketer prior to the time that there’s marketing automation, you’re pretty far removed from anything to do with producing revenue. You do branding. The closest you get is you put on events, you do field marketing things. Right? But you’re not producing, you’re not delivering leads in some old way most of the time.

Andrew Mitrak: Most of the time. Yeah, maybe there’s some direct response type things, but those are usually consumer-oriented and not for big-ticket B2B products, right?

Kerry Cunningham: Right. And they’re really small scale. So, you know, way back in the beginning of my career, I worked at some trade publications, and so you can get—you had direct response literally postcards from magazines and things. But it’s really small scale and not—it didn’t occupy an important space in anybody’s mind about how a B2B company was going to generate revenue. So it really was exciting, and I don’t think we should underplay that in thinking about the history of this because I think that’s a huge piece of it. It’s like, now marketing can be really close to sales. Marketing can participate in the production of revenue. For sellers now to be able to get these names of people who’ve come to your website that you have now, and they’ve filled out forms and looked at your content. I mean, this was very exciting, right? This is fun. This is a lot better than cold calling.

Andrew Mitrak: And if I think of that mid-2000s timeframe, the dot-com bubble bursting was not that far in the rearview mirror. There was still some skepticism around the value of the internet in some ways. Mobile and the whole world being online in the way that it is now still hadn’t quite happened yet. So there’s probably some—and then there’s a continuous pressure for marketing to show its value. What is the ROI of marketing and beyond things like brand equity and such. So it seems like a very appealing thing to adopt.

Standardizing the Demand Waterfall: How SiriusDecisions Solidified the MQL Framework

Andrew Mitrak: So you were a research director at SiriusDecisions, and they developed this Demand Waterfall. It introduced these popular B2B terms like Marketing Qualified Lead (MQL), and Sales Qualified Lead (SQL). So you joined after these had already been developed? Do you know how these were developed and what it was like, what did SiriusDecisions do to develop this?

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, so I can talk about that. I got there right after the last lead-based version of it was developed. My job for a couple of years was mostly to help marketers improve their execution within that framework. And what we discovered—not discovered, but a realization my buddy Terry Flaherty and I came to after a couple of years of doing that is like, there is no better that’s any good. You can just keep getting better at this, really, but it doesn’t change the outcomes at all. And so we changed it.

But the way that it came about was really smart people thinking really hard about what the process should be. And this is, I think, the thing that’s dangerous, and we always have to be on the lookout for. Right? So we’ve got this machine, marketing automation, that’s connected to our website, names come in. And so we think, “All right, what should we be doing to optimize the throughput of this system?”

And really smart folks at SiriusDecisions sat down and thought through all of that, worked with hundreds and hundreds of B2B marketing organizations, and I think came up with what I think is the absolute best set of things you could be doing if that’s your paradigm, right? The right checkoffs, the right handoffs, the right nomenclature to distinguish, making sure that at every step in the process when marketing hands this thing off to a BDR (business development representative), say, that we have a date stamp attached to that. We know when it happened, that when they work their process, we know how long that process is, and then we know when the next stage was reached. So working through all of that, and did that for, you know, eight or nine years, I think, building that process out so that you could have industry-standard benchmarks, industry-standard terminology, industry standards for what those handoffs ought to look like.

Along the way, they also introduced the scoring of leads because initially, these are just people who fill out a form, but now, maybe we don’t want them to just fill out a form. And I think, at some point, someone said, “You know, there’s a couple of ways we could go here. We could just look at the individual and say, well, how much content is that individual consuming? And what’s their title? Or we could look at whether we have multiple individuals from the same organization,” and the easiest answer was, “We’ll look at what the individual is doing.” And that’s the way all of the systems were built. And it was just the wrong way for it to be built.

Unintended Consequences: The Tragedy of “Second Lead Syndrome”

Andrew Mitrak: So, just to spell this out as an example, one company could have 10 people all fill out one form to get an asset, which is a signal. Or a company could have one person fill out that form and then click on an email and then do some other things. And that one person would get scored to be a lead, but that company that had 10 people all engaging would get ignored because they didn’t meet the scoring threshold. And so you’re kind of incentivized as a marketer to find more highly engaged individuals like that because then you get to beef up your MQL things, and you kind of ignore the harder challenge of reaching a bunch of different stakeholders in an organization.

Kerry Cunningham:

That’s exactly right. And to me, that’s the tragedy of B2B. What you just described is a massive tragedy. Now, it could be if you get 10 people from an account that come to your website and look at your content, they’re going to get themselves to be your buyer anyway. But you’re not doing anything to capture that or promote that.

So the thing that happens with that 10-person buying committee who comes to your website and looks at one piece of content each is, one, none of them become MQLs. Sales ends up talking to that account because eventually they come and say, “Hey, look, I’d like a demo.” And sales ends up talking to them. Sales puts it in Salesforce CRM or whatever as something that they found or something that came over the wire or whatever it is. But in the meantime, marketing has done all of this work to get these people to come and engage with content. It worked, and there’s no record of it. Like, no record that gets attached to the sales opportunity that gets produced. Right? So what marketing has done that’s been effective is completely unknown, remains completely in the dark. And it never gets connected to the sales opportunities that get produced and moved. So you lose an opportunity to understand what’s working.

It gets worse. We had this term we developed at SiriusDecisions when we were figuring all this stuff out called “second lead syndrome.” So most B2B organizations were structured such that if that first lead from an account comes across, goes to the business development rep who makes the calls, that’s great. If a second lead comes in the next day from that same organization, the BDR pay structures are typically that they can only produce one sales-qualified lead per account. So they look at the second one that comes in, and they say, “That’s no good,” and they mark it as a duplicate lead.

Andrew Mitrak: Right (shaking head) and it still happens!

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, I know it does. Yeah, that’s another tragedy, right? And one that you think, if you just thought about that for a couple of minutes, you would never do that, right? I mean, I’ve said—I’ve talked about this to like, literally thousands of people, and everybody goes, “Oh, you know of course, you know?” And yet...

And that’s why I think that this MQL industrial complex is a real thing. Because normal people under normal circumstances, it would occur to them that that’s dumb.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, it’s like, it reminds me—it’s like if there’s an open house and you’re a realtor, and a wife comes in to look at it, and then you engage her, and then the husband comes in afterwards, and you just ignore that person. Or whatever order it is, or another family member. Oh, that’s a lot of high intent, but it’s as if they’re ignoring that second person like, “Oh, I already talked to that family once, I don’t need to talk to them again.”

It would never happen in the real world, but somehow in these digitized systems and the incentives that get construed around it, it kind of makes everything sort of wacky, for whatever reason.

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, it completely distorts everything because everybody gets focused on this process that is in place and “How do I optimize that? How do I get my credit in that system, in that process?” And everybody was smart enough to think, “Well, that doesn’t make sense. Let’s do something else,” but nobody did because they’re just trying to optimize their particular outcomes in that process.

The Ripple Effect: How MQLs Reshaped Org Charts and GTM Strategy

Andrew Mitrak: We talked about the marketing automation platforms—the technology. There’s the SiriusDecisions of the world and the strategy and sort of the structures around it, it’s kind of a consulting complex on how to optimize this. And then also, it filters out into both marketing team org charts and how marketing teams go to market, or and even sales orgs also, and BDR orgs, go to market as well. Just like what tactics they prioritize, how they incentivize their teams. Do you want to speak to any of the other sort of marketing or GTM(Go-To-Market) org chart effects of adopting this complex in this time?

Kerry Cunningham: Well, it’s hard to remember, but 25 years ago, there really wasn’t a demand generation function. And now it occupies most of the budget for B2B organizations. And so, one, it introduced this whole new function whose job was really just to produce leads, because demand was recognized really only as the leads that you produce, the MQLs that you produce. That’s the output from that function.

And then you’ve got all of these functions that really do need to be there even without leads now, like RevOps (Revenue Operations) and those kinds of things. But all of those things are built on the back of, “Now we have to have this machine that really efficiently moves things from place to place.” And so you’ve got not just org charts, but industries built up around measuring these processes, attribution models, the measurement models.

And frankly, that’s the stuff that—that’s the real industrial complex stuff for me. Because once those measurement practices are put in place, once a person has a job of measuring how this process goes—I’m in marketing ops now, and I have this job and I measure that—you get software built to help do that. You educate CFOs on why this is the right thing. And now you’ve got other parts of the organization holding you accountable for how well you do that.

And so, in fact, today, I think one of the biggest reasons the MQL industrial complex hangs on is that people who built their careers in the last 20 years are now the leaders of organizations. And what they’ve known is an MQL industrial complex is, “How do we produce and optimize the production of MQLs?” And so they’re insisting that we have these objects, these MQLs, and all of the metrics associated with them when they’re no longer—I think most of the people close to the action already know that they’re not the right things, but they can’t get away with changing it.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, there’s sort of both the leadership problem, kind of a collective action problem of, depending on how large your organization is, you got a lot of different people who are invested in this system aligned with that. And then also it could make certain marketing tactics just not look very good. Or it could make a lot of that leader’s decisions look like, “Oh, you’re telling me that all that stuff I was celebrating over the last five years is actually just wasted?” “I don’t actually want to say that to my boss.” So it’s kind of a tough thing to wind up changing.

Kerry Cunningham: It is. Yeah.

Gated Content and the Rise of the BDR

Andrew Mitrak: You mentioned BDR, business development representatives, also sales development representatives—I think those are mostly interchangeable, SDR, BDR. Did that function also kind of emerge during this time of the MQL industrial complex? Because it seems like, did that org, did that exist more than 20 years ago, or is that kind of a new function as well?

Kerry Cunningham: It did, but it was all outbound. So, in fact, for a big chunk of my career, I ran a third-party teleservices organization, and what we did was find prospects for tech companies. But it was almost entirely outbound, 99% outbound.

Andrew Mitrak: And phone call at the time as well, probably was a more so than email, just because of the time frame. If it’s more than 20 years ago, not everybody had email in the same way or having cold emails wasn’t quite… There weren’t the ZoomInfos of the world or whatever other data providers there were.

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah. That’s right.

Andrew Mitrak: It seems to me like the thing that also sort of happens as a result of this is that there becomes this playbook of the marketing team creates content, and instead of just getting that content to as many people as possible, you put it behind a form because that form is how you measure something. And then what happens with that form is you start sending people a bunch of emails. And there kind of becomes this exchange where, “I’m going to give you something, but in exchange, you’re going to give me your email, and in exchange for that, I’m going to send you a bunch of emails you probably don’t want.” And that just becomes a whole mechanism that we all kind of have, there’s sort of like an invisible handshake that we all kind of agree to as a thing, which just sort of always struck me as kind of odd, is that that’s part of it.

When Buyers Got Wise: The Decline of the Form Fill

Kerry Cunningham: It is very odd. Yeah. It is. Yeah. So again, I mean, looking at it from the outside, you go, “Well, that’s kind of weird.” It’s kind of like the vendor is charging for the content about their solutions. And, you know, you could do well to ask the question, “Are they getting away with that?” I mean, you know. (Does that work?) And the answer is no, they’re not. Like, because we do this research now. We ask buyers, “Do you fill in forms?” And literally, we’re talking about one purchase you made in the recent past. “Did you fill in a form with the vendors you were looking at?” Two out of 10 people say yes. “Did you fill in a form to look at content with the vendor that you actually bought something from?” Three out of 10 people say yes.

So, you know, I mean, that’s horrible, right?

Andrew Mitrak: It’s a lot of folks that you’re like leaving off the table.

Kerry Cunningham: It is. And it’s almost certainly the people that you really want to talk to, right? Nobody who understands what’s going to happen would choose to do that. You know, so nobody wants to be chased, you don’t like it, we don’t respond to it. And so, if I’m a senior leader in an organization and my company is looking at vendors, what we know from the research talking to buyers is that they absolutely will go to the vendor websites. And if you think about it, even the CFO for a reasonably sized company, if they have to sign off on a deal, if it’s like a big enough deal for them to have to sign off on it, they’re going to come to your website and look around, you know? And they probably already know you anyway, that’s a different story, but they’re going to come poke the tires. They’re certainly not going to fill out a form.

So what message do you want to deliver to that person? What level of comfort do you want the CFO to have or the head of purchasing to have when they come to your website? What experience do you want that to be? If you were thinking about that, you would never put a form in front of it, right?

Andrew Mitrak: Do you think that the consumer behavior changed over the years? Like, I wonder if there was the—so there’s, there’s the tech, there is the, um, you know, demand waterfalls kind of created and this concept of an MQL. There’s marketers changing their behavior and starting to put things behind forms instead of just making it available. And then do you think at some point a hypothesis I might have is, maybe early on, maybe for the first few years of this being a thing, CIOs (Chief Information Officer) and important decision-makers might fill out a form, but by now they’ve all caught on to the game. They know at this point, since this is so saturated and it’s become such an abundant practice, that, “Okay, I fill out the form, I get a bunch of emails I don’t want. I’m not going to do that anymore because I’ve been bait-and-switched too many times. I’ve had too many instances where the content wasn’t actually that great and those emails I got were kind of annoying.” Like, do you think that they changed their behavior over time, or do you feel like it was always kind of the case that CIOs and other important decision-makers just wouldn’t bother with a form?

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, I would, I think there probably were a few years back in the beginning of this, but I think you only need to go through a cycle of being hounded to decide you’re not going to do that again. I don’t think it took long. And when we look at the, I think the earliest research I could find on form-fill rates just looked at the number of form fills against the number of web visitors, and that was about 3% 12 years ago. It’s 3% today, overall. So, you know, that has a lot of junk and it has bots and all of that stuff. So the real relevant numbers are how many members of a buying group, our actual, you know, legitimate one will fill in a form. And that’s the more two out of 10, three out of 10. And I bet that hasn’t changed very much.

And again, it’s a thing, you know, so think about content marketing is a huge part of this MQL industrial complex, right? Because it was built—content marketing exists, so that’s another, that’s part of the organization that really, that’s part of the org chart that is built to buttress this MQL industrial complex. And it’s a trick, right? It’s just a trick to get people to fill in the forms. That’s all it is. It’s a trick. But the better you get at that trick, the more likely it is that you are going to bring people to your website to look at your content who are actually not in-market. Like, if you have crappy content, the only people who are going to be coming to look at it are the people who want to buy your stuff, or they’re looking at you and your competitors. But the better you get at it, the more traffic that you get that isn’t going to be in-market right away. And that’s going to make everything that you’re doing look worse within the complex of the kinds of measurements and things that we have. So your conversion rates will go down. Your number of visitors, traffic, and all of that will go up, conversion rates go down.

Now, that’s great if you actually are just worried about selling stuff. Right? If I just, if I just care about whether we’re going to build buyers who are engaged with us and like our content and all of that stuff, then I don’t care about conversion rates as form fills. I care about conversion rates of accounts to whether they become customers. So if I’ve got great content and people are loving our brand and learning about our solutions, does it matter that they filled in the forms? Well, it matters to you because you get measured on whether they fill in the forms. It does not matter to them, the buyer.

And that’s the, that’s the disconnect that happened, and where it just, we became blind to the fact that we’re just focused on our own goals and trying to, you know, the process is really about us trying to get what we want. The buyer is kind of getting what they want. I mean, even if they do fill in a form or they get a junior person to go fill in the form, they get the content, they get it from somebody else, they get what they need. They’re going to get what they need. But you’re not going to get what you need, and it’s going to look worse all the time. And that doesn’t make any sense.

And so if you’re a marketer and you’re trying to justify your existence, your ability to justify your existence is continually declining. The ROI numbers based on leads that end up on opportunities continue to go down because, as you said, people are wise to the trick, and they’re not going to engage in that trick. And you can chase them all you want, they’re still not going to respond. We’ve got a lot of stats on that from our buyer research. So buyers, if you ask them when do they talk to BDRs or sellers for the first time, it’s 70% of the way through their buying journey. And if you ask them, “Did you initiate contact, or did the vendor initiate contact?” buyers say that they initiated contact more than 80% of the time. And again, if you ask them, “But were you being called and emailed?” the answer is yes, almost all the time. But buyers choose the timing of when they’re going to engage, and that timing does not change simply because you’re calling and emailing them.

And, you know, when I talk to marketers, I just think, “Well, just think about yourself. Does a BDR emailing and calling you ever change your behavior at all?” Right? Do you change, do you do anything differently because people are calling and emailing you? Of course not. You know? I mean, you’d never even would dream of it. You know, if you like the vendor, you put the email in the folder and you hang on to it for when you want it. You’re not going to respond. I mean, you know how that’s going to go if you do. All right? So, no, of course you don’t.

Was the MQL flawed from the start? Or have we just outgrown it?

Andrew Mitrak: Reflecting on this system as a whole is your overall take that it was misguided from day one and was like a mistake that was like fundamentally flawed? Or is your take more that it was appropriate for its time to some extent, but we can do better now because we have better technology and better insights now? Or what’s your overall kind of assessment of sort of the whole era?

Kerry Cunningham: I would say it was fundamentally flawed from the beginning. There, it would have been complicated to fix from the beginning. It would not have been complicated to know that it needed to be fixed. That’s really what got lost in, and that’s why I focus on this complex idea, because it’s not just the technology, right? The technology got there, but the technology and the process and the measurement and all of that, it has an enormous weight to it that squelches the very simple thinking that would have said, “You know what? Okay, this is what we can do today, but by three years from now, we’ve got to notice when we have three members of the buying group that show up and fill out our forms.” Or, maybe since marketing has known that, say, the form-fill rate is about 3% to 5% for the last 20 years, marketing could have said to themselves, “Well, you know, all of those people that are coming to our website, we’re paying for all of that. And I wonder if there’s anything we can do to understand what’s in the rest of that web traffic.” And the answer has been yes for a really long time, right? Because it’s practically all, you know, I tell folks, look, if you’re paying to bring people to your website, the outcome from that is almost all anonymous traffic. That, I mean, almost every penny you spend results in anonymous traffic. So if you’re not doing everything that you can to legally understand what’s going on there and and which accounts are on your website, that seems like malpractice, you know? And but you’ve got a whole industry engaging in malpractice. It doesn’t really hurt you.

Beyond the Waterfall: The Shift to Buying Groups and What Comes Next

Andrew Mitrak: I think the natural next question is, “What comes next?” What takes its place? Also, do you have any examples of companies or individuals who sort of bypassed this complex entirely and sort of just operated outside of it? Do you have any ideas or successful stories of who’s marketed outside of the MQL industrial complex?

Kerry Cunningham: We do. A little bit of this may seem self-serving, but I can talk about some of the, some of the things that we that have been done. So one, you know, back at SiriusDecisions, we ditched the old lead-based waterfalls and built a completely new one that was based around this concept of buying groups and noticing that there were buying groups. So that was back in 2017. And, you know, hundreds of companies have adopted that way of looking at the world. And some of the biggest companies in the world are still doing it. My friends back at Forrester, which bought SiriusDecisions, are still working with companies and getting them to adopt that. And and some of the really big companies are doing that.

The reason I came to 6sense is because they’ve got a machine that’s built for identifying buying group-level signals. So, do you have multiple leads? We can show you that. Do you have anonymous traffic from those same accounts? We can show you that. Is there third-party signals outside of your website? Right? We can show you that and bring those things all together. So we’re not the only ones, there are others as well, but that’s the, that’s the answer. And the technology for doing that is actually really mature. It’s been around for quite a while, it’s been around for 10 years, but it’s mature now. It’s, it’s attainable by everybody. And so, I mean, there are, there are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of companies that are doing this the right way, at least for part of their go-to-market practices. So, you know, we, part of this, the weight of the MQL industrial complex led people to do some really bad things like saying you should have both a lead-based and a buying group-based waterfall at the same time. No, that’s stupid. Unless you sell to individuals and you sell to big companies. As long as you sell to companies, you should be focused on buying groups, buying groups alone.

PLG: Reconciling Individual Users with Buying Group Intent

Andrew Mitrak: There are a lot of companies that do both. They have some freemium model, they have some land-and-expand model, they have some, but I guess that is a little more of like a product-led growth type thing where if you have a user signing up for a product or some trial or or some lighter weight account, it is a little bit different than them filling out a form for a PDF or something and becoming like an MQL. So I guess what, what is, how do those things kind of coexist?

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, so I think of the product-led growth lead, somebody who signs up and does an individual user of your license, as a slightly better MQL. If what your aim is to sell enterprise licenses, the fact that one person in a 10,000-person company is using your thing is better than if no people are using it. How much better is it? If you don’t see any other interest, it’s not any better. You know, it’s just like, you’re not going to go sell them anything just because one person downloaded and is using your thing, right?

Andrew Mitrak: It kind of depends on the type of product someone. I think Figma, it’s like, oh, it’s, it’s kind of had virality sort of embedded in the product where one user uses it and they share it with somebody or, “Oh, and to see this design, you have to create an account.” And then, then all of a sudden you kind of have a buying group because you have a number of users who are using it, similar with Zoom, you know, because you have to have multiple people to communicate. It’s a better MQL in that, and it really becomes impactful when multiple people use it within an organization, which leads you right back to the buying group framework.

Kerry Cunningham: Well, exactly right. So I think, you know, it’s a great signal to have if your product allows you to have that kind of delivery mechanism. That’s great. Now we want to look at all of the signals that would tell us whether the rest of that organization is in-market. And, you know, the key is just being able to to spend your resources in the place where it’s likely to do the most good. If you’ve got a potential 500-user account and there’s one user there and no other signals, it’s just not a good, it’s not a good bet right now. If it’s a great account for you, good fit, I wouldn’t, I’m not saying ignore it, but I’m, they’re not in market now. But if you have another account with no downloaded users because their policies don’t allow it, but they’ve got 50 people on your website, you should be paying attention to that one first.

Beyond the MQL Industrial Complex: Are “Signals” the Future?

Andrew Mitrak: On this topic of what comes next for marketers, what is your sort of vision for replacing the industrial complex? What are the big things that sort of need to fall into place to have sort of a new paradigm adopted?

Kerry Cunningham: The concept of signals is a really important one. Back at Forrester in 2020, a colleague and I did a report called the Buyer Signal Framework. And that was our way of saying, here’s how we step above the level of the lead. We know that there’s the lead, there’s anonymous traffic signals on your website—far more valuable than whatever leads you have—and then there’s all that third-party intent signal, plus there are other kinds of signals as well.

So, I think, first of all, we need to adopt a signal-based approach to understanding the market. And I don’t think that has an expiration date on it. You know, we have to have a pretty expansive view of what those signals can and should be and be continually updating that perspective.

The thing that we struggle with still in B2B, in marketing, is we have had, through this lead-based process, a very top-down view of how we understand which buyer is good. Because, you know, we’ve said going to this web page is worth 10 points and going to this one is worth 20 points or whatever. We’ve controlled that. And I still see a lot of marketers want to look at big data the same way. So, we’ve got literally—we process, 6sense processes, a trillion signals a day at this point.

So marketers need to leave behind this idea that they should start with and have a top-down control over how they understand which buyers are in-market. That’s not the way it works in the world today. It’s a signal-based view. We use AI to understand the patterns, and that’s what we should be looking at, is all the signal we can, use AI to understand the patterns that betray a buyer that is or is not in-market, and then where are they. And you don’t need to be an expert in AI or in big data for that. What you need to do is really understand a little bit of just what’s possible. And what’s possible is we can know a lot.

Because buyers now have so many resources. There have been so many tricks set up across B2B, across the digital universe, and all of those tricks are selling their data. And so when people go anywhere, whether anonymously or known, to look at data and content or whatever, they turn into a signal. So it’s kind of, you know, the bad news about the industrial complex is we were looking at the wrong, we were looking at it through the wrong lens. But if we broaden the lens and step back and say, “All right, instead of looking at the individual, we’re going to look at the buying group or the broader organization to understand what they’re interested in,” we’re looking at much of the same data, but we’re looking at it in a different way that is much more diagnostic of the thing that we’re trying to find and to engage with. And so I think that’s the, that’s the perspective that everybody has to have. It’s like, you know, the data is out there, the technology is out there. What we have to do—and even if you’ve got your leads, okay, great—but we have to look at them differently.

Avoiding the “Signal Industrial Complex”

Andrew Mitrak: The thing that I’m completely on board with is getting rid of the forms and you know, don’t try to trick people behind a form and all that. I agree a lot of the MQL stuff is wrong.

The thing that I would worry about with a signal-based approach is that you develop a signal industrial complex that eventually people learn how to game. And then also there’s not all, not all signals are created equal, not all people who collect signals or sell signal intent data are of equal value. That there’s, there’s sort of folks... I’m not going to name names, but folks who I’ve evaluated or purchased from where, “I think that signal stuff that I paid for was mostly snake oil, and I didn’t see any benefit to it,” right? And, and, um, and I wonder how do you set it up? But I, intuitively, I think it’s the right thing, though. Like, it’s like, okay, obviously this is much better and that there are people who visit websites, there are people who engage with content, there’s data everywhere. And if you can make use of that data, you’re going to have a much, you know, better success at understanding the effectiveness of and what marketing is working.

It’s just like, how do you, how do you set it up in such a way that you’re not 20 years from now talking about, “Oh gosh, that signal, that signal-based marketing industrial complex was a bad idea.” How do you kind of set it up with the right guardrails in place so it sort of is indeed an improvement?

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, so I think the process has to be set up to collect or use as much signal as possible to make zero assumptions about what any of it means and to apply math on top of it to identify patterns and not try to outsmart the patterns. And so there’s two places, I think, where we get in trouble. One is we try to decide what signals we think should matter instead of just getting them, you know, bring them all in, put them in the bucket, and let the AI, which, you know, really, predictive modeling, which has been around for a long time, is a form of AI. And it’s really all we’re doing is we’re looking at the signal and trying to identify. So what we want to do is just avoid making any assumptions. That’s, and it’s difficult, right? It’s difficult to do that because we want to say, “Hey, I know, we’ve done this before,” but no, you have to just let the data and the math do its job, build that model. And then the model will tweak and adjust as you move. The times change, what happened last month may not predict what happens next year very well. So, you know, those things have to be—we have to adapt to those things. But what we can’t do is panic the first time it doesn’t seem to be working and say, “Okay, shut it off, let’s go do, let’s, you know, go do leads again or something like that.” It’s just, you know, and that’s a difficult thing for us.

Andrew Mitrak: That’s right. There has to be some understanding that, hey, those dashboards that we used to have, we expected those to all drop down significantly. And you have to kind of go to a new paradigm and mindset shift, which could be a little scary, but it’s overall, it’s it could be a much better outcome.

Kerry Cunningham: One of the big fears that happens that prevents organizations from really scaling this approach is if you take away the forms from in front of the content, you don’t have all of these names coming in. All of these names made you feel comfortable and like you had some control over what was going to happen next. The truth is you didn’t. You know, there was an illusion of control.

Kerry Cunningham: But I use this analogy, probably makes some people angry, but, you know, in psychology when they do the experiments and they teach pigeons to press the button to get the pellet, other forms of that experiment are they drop a pellet at random times, right? And does a pigeon just say, “Hey, every now and then a pellet drops in, I’ll just wait for it to happen?” No, they do not. They develop behaviors that are highly personal to each pigeon that they believe are causing the pellet. So if they were just spinning around and pecking the ground before the pellet dropped in, the pigeon, in whatever ways pigeons think, think, “Huh, okay, spin around, peck the ground. If I need another pellet, that’s what I’m going to do.” And that’s what they do, right? And if it doesn’t work, which it won’t, then they’ll think, “Ah, okay, maybe I wasn’t doing it right.” They don’t think, “All right, never mind, I’ll just wait.” They think, “I’m not doing it right,” and they spin around twice, and maybe that works next time, right?

So you get, you could have cages of pigeons on a bench in a lab, each with their own superstitious behavior about what causes that pellet to drop. And that’s exactly what we’ve been doing in B2B when we have these leads and we call out. We have all of these superstitious behaviors. “Oh, maybe if we call them 12 times, maybe if we call them 15 times.” But there’s like no canonical—you would think, you know, in B2B, across all of this time, with the billions of dollars that have been spent, the smartest people on the planet have been working in B2B, and nobody has come up with the right sequence to run to qualify a lead or to do something else or to do—there’s like nobody who can, you could point to and say, “That’s it.” In all this time, we figured it out, that’s how you do it. Why? Because there isn’t a figured-it-out. You know, it just doesn’t exist.

Andrew Mitrak: That’s great. I love those analogies. The other one, I read this in a book somewhere, I don’t know which one, but it’s an analogy that I’ve used, and it’s a little bit of a joke, so here it goes:

A man walks out of a bar, and there’s a drunk down the street under a street lamp, and he’s looking around. And the man walks up to the drunk person and says, “What’s what’s going on, sir?” He says, “I’m looking for my keys. I dropped them as I was leaving the bar.” He’s like, “Well, the bar’s down there. Why are you looking over here?”

And the drunk man replies, “Well… this is where the light is.”

And he’s looking in the spot where the light is, where the signal is. And I feel like that’s sometimes what we do as marketers, too. We are able to measure this one thing, and so that’s what we search for as well, where there’s this whole universe of other things to look for but we ignore because they’re harder to find and inconvenience us.

So it’s like we’re attracted to this one little small area instead of seeing the bigger picture.

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, it’s a big part of it, right? Because there are lots of forces that keep us kind of doing the wrong things collectively over time, and that certainly is one of them, you know, the ease with which that has been looked at and tracked.

Practical Takeaways for the Modern Marketer

Andrew Mitrak: Just reflecting on this conversation and the MQL industrial complex, the anti-MQL manifesto, the benefits of signals, do you have any other takeaways for marketers? I don’t know if any one of us individually can change the whole system, but what can we do if we’re operating within a certain system or we’re, you know or we just want to be better marketers? What could we, how can we make use of this information to be better at our jobs?

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, so there are some things I think everybody can do without really a—well, a little, maybe a little bit of additional tech if you don’t have it right away. But first of all, look in your own—if you have, if you’re producing leads today, look in your own leads data and understand what that looks like. So we started doing this again a long time ago at SiriusDecisions, and this is what brought us to an understanding of buying groups. Because when you look at leads data, what you see is that there’s typically between one and a half and two and a half leads per account. And that’s if you just take all of the leads and you just sort it by domain and and that’s what it looks like. So immediately, if you’re being judged based on conversion rate to opportunity and you know that you’re only going to get one lead at the most on an opportunity, you’re being screwed already by, you know, by half, at least, right? Just looking at that.

And that can be a revelation for people in the organization. Like, “Look, this is what it looks like.” And then at least, at the very least, start doing a report monthly, weekly, that shows how many leads are we getting per account and deliver that to sales leaders and have a conversation with the sales leaders to say, “Hey, look, you know, maybe right now we’re looking at these as duplicate leads, but here’s another way to think about it. You know, this is evidence of interest from this organization, multiple levels of interest.” So start introducing those concepts today, but do it with your own data. You know, take our reports, they’re all free to download and all that from 6sense, but take that, take that data and show, “Here’s what the industry looks like, here’s what B2B looks like in general,” but always look at your data and say, “And here’s what it looks like for us,” because everybody’s going to say, “Yeah, but for us.” So you’ve got to do that homework.

Then, if you have a tool that does any sort of website de-anonymization today, use that. Get in the sales cycle for 6sense, we’ll do it for you, but you’ve got to see the anonymous traffic on your website because that’s the vast majority of all signal you’ll ever see. And what you want to see is, one, if we get multiple leads from an account, that very first thing, is that account likely to end up in a sales cycle, and are they likely to go deep? And you can even do something that says, “All right, so if we get one to two leads in an account, how likely are those guys to become pipeline? If we get three to five, how likely are those accounts? If we get six to 10, how likely are those guys?” Right? So you can start to look at the impact of having buying groups engaging with you and the likelihood of those, of sales getting a better outcome. Because now we can show that to sales and say, “Look, this is how our buyers are already buying, and what we want to do is make sure that our processes reflect what’s happening in the data so that we don’t miss.”

Because what you can also do, and you will see frequently, is that, “Here’s an account where we got three form fills in this two-month period of time, but there was never any action on the account.” That’s probably a lost deal, right? That’s probably a deal that went to somebody else, and we just never did anything with it. Maybe those people all filled out a form, none of them scored up and became your MQL, so nothing happened. That’s the 10-person account. Go look for those. You’ll find them in your data. They’re there, right? Use the anonymous traffic the same way. All of those things can help build the case internally for why we just need to look at this differently. Even if you don’t want to take—like, and I don’t recommend taking all your forms off until you’ve had these conversations internally, until you can see this, and until you’ve built a mechanism where you can say, “Here’s a report that shows we’ve got multiple leads, let’s prioritize that account.” Right? So you’ve got to have a process for doing that.

Same thing with the anonymous traffic. I mean, it’s a mistake to take a report that says, “Hey, we’ve got five people on our website anonymously, sales rep, go call on that account.” Your sales reps are going to hate that and are going to throw up all over that. They’re going to want the name. But if you’re the marketer, what you can and should do is say, “All right, well, here’s a set of accounts that have had an extraordinary number of people on our website this month, and we don’t have any of the names that we would like to have. Sales isn’t taking action on that account. What can we do to drive the kind of engagement that we need in this, what will be a very small set of accounts?” Right? So if you’ve got, you know, pick a threshold, but if we have five or more people from an account on our website anonymously this month, you know, for 6sense, “All right, do we know their CMO? We sponsor a community for CMOs. Is that CMO part of it? If not, that CMO should get an invitation to that right away,” right? And if we have any events coming up that are wine tasting events, dinner events, those kinds of things, you can’t do them for everybody. But if you’ve got five accounts a month that are on your website and deeply engaged, but you don’t have the right people to talk to and sales doesn’t want to go do anything with them yet, then that’s a perfect set of accounts to find another set of much higher-value experiences for those accounts to drive some engagement, to get, you know “You’re looking at us, right? So we’d like to buy you some wine. So let’s get together.” You know, that actually works. You know, it actually, those kinds of things actually do where you’re providing—or maybe it’s something that’s more work-related. “We have subject matter experts that you could talk to about given things. We have other kinds of events that you could go to.” So it’s building much more engaging kinds of experiences for your buyers. And then, you know, you’re not going to be able to deliver those on mass, but what you can do is identify the set of accounts where you should be delivering those, not just the good-fit ones, but the good-fit ones where you’re showing engagement where we’re not really there yet. It’s going to be a very small number of accounts relatively for anybody. But you can do some extraordinary things for those accounts and for the people inside them that you’ll be able to afford to do or more likely be able to afford to do because the number of them by then will be so small.

Read Kerry’s Research Online

Andrew Mitrak: Thanks for all of those insights, those tactics, those tips. Kerry Cunningham, I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. One last question is, where can listeners find you online and read more of your work?

Kerry Cunningham: I’m on LinkedIn all the time. So, Kerry Cunningham on LinkedIn. I think there are a couple, but I’m pretty easy to find related to B2B stuff. And then on the 6sense website, there’s 6sense.com/research. We call it the Science of B2B. And all of our research is there. There’s videos, there’s, you know, dozens of reports, both about buying and about marketing processes.

Andrew Mitrak: I’ve read through some of that research and really enjoyed it and appreciated the thoroughness of the work and the data that backs all of your insights and recommendations. So, Kerry Cunningham, thanks so much for being on A History of Marketing. I really enjoyed the conversation.

Kerry Cunningham: Yeah, thank you.