A History of Marketing / Episode 37

This week, I’m sharing a special conversation with Scott Reames. Scott spent three decades at Nike and for 16 years was Nike’s official corporate historian, a role he invented. He even helped Phil Knight with research and fact-checking for Shoe Dog, the only business memoir I’ve read more than once.

Nike is the first brand I remember embracing as a kid. I suspect this might be true for a lot of marketers.

Growing up in the 1990s, I played basketball, I watched Michael Jordan win six NBA championships, and my favorite movie was Space Jam (which, as we’ll discuss in this episode, originated as a Nike ad).

Nike is the gold standard for branding. They set the bar for iconic advertising, bold messaging, and culture-defining sponsorships.

But how did they build their marketing empire? Who were the marketers responsible?

In our conversation, Scott shares the stories of Nike’s most important marketing milestones and the people behind the brand.

Nike’s brand wasn’t built by seasoned marketing experts, but by a group of self-taught mavericks in Portland, Oregon with passion, ambition, and good instincts. Their professions: an accountant, a social worker, a lawyer, and a student.

In this conversation, Scott shares:

How Blue Ribbon Sports (Nike’s original name) established its early reputation in the running community with the help of cofounder Bill Bowerman.

How marketing helped Nike win a legal battle against Onitsuka, allowing it to continue as a brand.

The story of Rob Strasser, Nike’s first head of marketing, who started as the lawyer on that Onitsuka lawsuit.

The real story of the movie Air, and how Hollywood gets so much wrong.

The surprisingly morbid inspiration behind “Just Do It”.

Here’s my conversation with Scott Reames.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts

Thank you to Xiaoying Feng, a Marketing Ph.D. Candidate at Syracuse, who volunteers to review and edit transcripts for accuracy and clarity.

Nike’s Secret Sauce: ‘We never sold shoes. We sell dreams.’

Andrew Mitrak: Scott Reames, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Scott Reames: Thank you for having me. I’m excited to talk.

Andrew Mitrak: I’m so excited to talk about the history of marketing at Nike. And as I was preparing for this interview, I was thinking, is the history of marketing at Nike just the same as the history of Nike?

Scott Reames: It’s funny, I was thinking about a quote I have from Jeff Johnson, who was the first full-time employee hired in 1965, right? So, Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman, the co-founders, were working full-time at their own jobs, and they hired Jeff to essentially be boots on the ground and really do everything: start the marketing, start the advertising, start the product development, everything.

And he told me years ago, he said, “The secret sauce for Nike, Scott, is we’ve never sold shoes. We sell dreams.” And to me, that is like the epitome of marketing. I mean, that literally is marketing. It’s marketing a product by going well beyond just, “Here’s what it does for you, here’s how it wears, here’s why it’s good for your foot,” that kind of stuff.

So yeah, I would say if that was the mindset in 1965, then it certainly was a part of the fabric of what developed later into the company of Nike.

The Bold Early Days of “Blue Ribbon Sports”

Scott Reames: I mean, Phil Knight, there are some early letters that Phil Knight wrote to early retailers and coaches as well, but mostly retailers. And at the time, Nike started—or Blue Ribbon Sports started—as an Onitsuka Tiger distributor, not it didn’t have its own brand yet. And Tiger is now ASICS for those who aren’t as familiar. So we were the distributors of the Tiger brand running shoe in the United States.

And Phil created a letter, I think it was also in 1965, might have been ‘66, where he didn’t name the runner, didn’t name the athlete, but said that there was a runner, a high-profile runner who had been running in Tiger shoes and felt that they were one of the greatest shoes ever. And he said something along the lines of, “The only people who won’t be running in the shoe are either uninformed or idiots.” And then Phil at the bottom wrote, “And now you are no longer uninformed.”

I was like, wow. I mean, talk about a not-too-subtle dig at coaches and retailers. So from the beginning, there’s been that understanding that Nike, or Blue Ribbon Sports then Nike, maybe looks at things a little differently.

Andrew Mitrak: That’s a bold line. There’s so much there. So, Jeff Johnson, who I’ll ask more about, he said Nike doesn’t sell shoes, they sell dreams. But in the early days, and you mentioned this, they weren’t Nike at all. They were Blue Ribbon Sports, and they were selling Tigers, Onitsuka Tigers. I actually, Onitsuka has re-released these, and I wear Tigers a lot.

Scott Reames: Nice.

Andrew Mitrak: Like they’re actually pretty good shoes. They’re kind of that old, I don’t know how much they actually match the original style of it, but I like Nikes of course, but I do also like my Tigers as well, those branded ones. And so, do you think that Nike in 1965, were they making marketing decisions? Or what was sort of the original Blue Ribbon Sports approach to marketing?

Scott Reames: I think in the earliest days—‘64 was when the partnership started and the shoes started getting delivered from Tiger. ‘65 was when the first outreach really began. So the original, early marketing was really mostly done by Tiger because Nike was just… I keep calling it Nike, it’ll be interchangeable, but Blue Ribbon Sports, because Nike didn’t exist yet, was just the distributor of the Tiger brand shoes. They didn’t do a lot of their own marketing. They mostly sent out the flyers that that Tiger had sent to them.

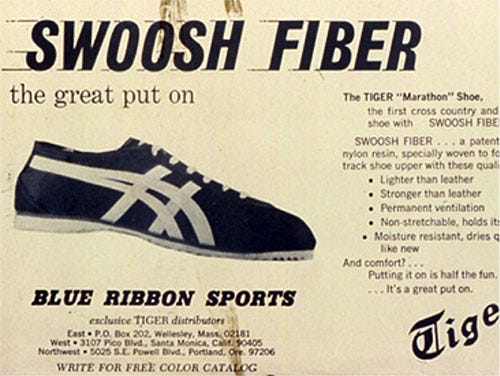

That started to change as the ‘60s progressed. Jeff Johnson started to be more involved in creating the flyers that would be used in the US. By the end of the ‘60s, Phil Knight is actually writing some copy. He actually coined the term “Swoosh fiber” that was used to describe basically nylon, the nylon uppers, in a 1969 print ad. So that was the first place that we can see the word Swoosh being used, and obviously becomes important later.

How Marketing Won a Landmark Legal Battle

Scott Reames: But throughout the ‘60s, what Nike, Blue Ribbon Sports, did was increasingly taking over the marketing of Tiger, at least in the United States. To the point that when the two brands did part ways in the ‘70s, and they each sued each other for breach of contract, the judge ruled in Blue Ribbon Sports’ favor in terms of who owned the names like the Nike Cortez, the other shoe brand names, that we—they said Nike owned them because they had done the marketing of those products. And so it’s like Bill Bowerman designed the Cortez, and they ruled, the judge ruled that neither Tiger nor Blue Ribbon Sports owned the design of the Cortez, but that Blue Ribbon Sports owned the name of the Cortez because of the marketing they’d done of it.

So those are anecdotal, but those are indications that the company was starting to realize the benefit and the power of marketing and advertising.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, so marketing helped give them a legal win early on.

Scott Reames: Which was critical because if you lose that, if we lost that case, I wouldn’t be talking to you today.

Andrew Mitrak: Exactly. There are so many places where the Nike story seems like it could have just flipped a coin and could have gone either way. One of those, really early on, Phil Knight, I think he’s in Japan, and he comes up with the name Blue Ribbon Sports because he needs a company name. I’ve heard a few versions of the inspiration for that name. What do you think is the real story?

Scott Reames: Well, one of the versions I bet you’ve heard is that it was his favorite beer, Pabst Blue Ribbon. That was lore and/or myth that was spread mostly by his contemporaries and others of that era who just liked to tease him. And he never really went out of his way to correct them. He just thought it was funny.

But when we were working on Shoe Dog, he obviously wanted to really tell the story correctly. And he admitted there that no, he didn’t… while he did kind of BS his way into a meeting with the Onitsuka—well, with the president of Onitsuka—that when they said, “Who do you represent?” he was prepared that that question might be asked, and he answered “Blue Ribbon Sports,” because as a track athlete himself and just in general, a blue ribbon signifies first place or it’s a great thing to earn when you’re in Little League or sports in general. So he felt “Blue Ribbon Sports” telegraphed the message that this was a quality company, even though it didn’t exist.

Andrew Mitrak: It’s so funny just to contrast the name Blue Ribbon Sports to Nike. Like one just kind of seems so generic, vanilla, it’s a distributor, right? And the other is so branded and is kind of abstract and all that. And you have to kind of create new meaning into it. It’s not obvious what Nike is until the brand exists. So it’s just funny to contrast the two.

Scott Reames: That’s correct.

Bill Bowerman’s Credibility and the Birth of an Empire

Andrew Mitrak: So, Phil Knight’s early partner was Bill Bowerman, the co-founder of Nike. And Bill Bowerman, he gives all of this credibility and reputation to Nike as a brand. So do you almost think of this partnership somewhat as a marketing decision to work with Bowerman, or how do you think Bowerman improved Blue Ribbon Sports’ marketing presence?

Scott Reames: Well, certainly his name, the gravitas of his… I mean, literally the University of Oregon had won its first track and field title, NCAA title, in 1962. So he was certainly a rising star in track and field coaching. And the university also was starting to register some A-level runners. There was a man named Otis Davis that ran in the Olympics in 1960 who was a Duck. So it was basically a program on the rise.

And obviously Phil Knight, having run for Bill Bowerman, also had a personal affinity for it. But I do think it was a little bit of mercenary, a little bit of certainly wanting to make a sale, obviously. I mean, Phil’s trying to get his fledgling company off the ground and making a sale to the University of Oregon would not be a negative thing in any way. And then also being able to say that the Tiger brand running shoes are the shoes worn by the NCAA title, you know, NCAA champion, University of Oregon, certainly had its own cachet.

Whether that was done completely with forethought as to the marketing side of it, or it was just literally, where else would you start as a Duck alum? You know, Phil’s not going to go to the University of Washington, right? He’s not going to go contact USC. I mean, maybe eventually, but he’s going to start at home. So I don’t know if it was overtly a marketing thing like, “This will be amazing.” I think he didn’t have any idea that Bill Bowerman would ask to be cut in as a partner. He was just looking for a sale.

And the main reason for that is the reason why he didn’t expect him to cut in as a partner was that he, Phil, did not have any knowledge of the fact that since at least 1954, Bill Bowerman had been contacting Adi Dassler, Horst Dassler, other members of the footwear cartel at the time, trying to get somebody to sell him shoes directly instead of through wholesale so he could get them less expensively. But more importantly, he also had design ideas that he wanted to impart and have put into a running shoe. And all he would get back from Adidas and others was, “Thank you for your interest. You can get our shoes at through such and such distributor.” And they made no mention at all about any interest in his design ideas.

So Phil is just reaching out to Bill to get a product endorsement and a sale. Bill sees now an opportunity to have a connection, a direct connection to a footwear manufacturer who might take his ideas and actually turn them into something. So it was a very serendipitous exchange of letters that led to the partnership that led to Blue Ribbon Sports, which led to Nike, which led to you and me being here today.

Andrew Mitrak: Right, yeah. And then so for listeners, Adi Dassler, obviously Adidas, and then the other brother, is it Rudolf Dassler?

Scott Reames: Oh, sorry, Rudy, yeah. Horst was the son. I forgot about that, sorry.

Andrew Mitrak: Rudy was Puma. Which is its own really fascinating history there that we won’t go into...

Scott Reames: I mean, there’s a great book called Sneaker Wars. It’s absolutely fascinating about the two brothers and how much they didn’t like each other.

Andrew Mitrak: Totally. Yeah.

“If You Have a Body, You Are an Athlete.”

Andrew Mitrak: So one of Bill Bowerman’s lines is, “If you have a body, then you are an athlete.” And I love this line, and it’s just like, what a great turn of phrase, and also really expands your addressable market as well.

Scott Reames: Yes.

Andrew Mitrak: Did Nike or Blue Ribbon Sports ever use this line publicly? Or how was this used?

Scott Reames: No, not in the earliest days. It didn’t really… he may have used it to his own, in speaking to his own people or in his own communications with others, but Nike didn’t start using it until 2001. There was the Nike mission statement in the earliest days was essentially to be the world’s leading sports and fitness company. Right? Okay, well, it’s a good goal. We don’t want to be number four, you know? It’s like we want to be the world’s leading.

So by 2001, check. They’d done that. So it was kind of like saying, well, we want to be what we already are. So Mark Parker, the co-brand president, or co-president at the time, decided that it was time to change the mission statement. And they went around and around, and basically they decided to be more aspirational instead of literally achieving a specific goal. And so it was like, to bring innovation, innovation, inspiration, and innovation to every athlete in the world. And the athlete had an asterisk. And then if you look at the asterisk, it said, “If you have a body, you’re an athlete.”

Which is about the most inclusive way you could… I mean, there can’t be a more inclusive slogan, as you were saying earlier. I mean, literally, we all have a body. We can all be athletes. We can all, you know, we can’t all be Michael Jordan or Serena Williams, but we can certainly be more athletic or we can do something that is athletic in our own way. So that was when it really took a high profile within the company. Again, how it was used before that, I don’t know. That was the first time, and since then it is a key part of the mission statement.

Phil Knight’s Skepticism and the Ad that Changed Everything

Andrew Mitrak: So back to Phil Knight and the early Blue Ribbon Sports story, I read that somewhat ironically, Phil Knight was skeptical of advertising. So when did they really start advertising beyond just sort of republishing Onitsuka’s brochures? What were their first early forays into advertising?

Scott Reames: Really, beyond just the one-offs that were done like Carolyn Davidson, who designed the Swoosh, she also did some early advertising, but those were very one-offy. There wasn’t really a program put together, per se. That really came about in the mid-70s when we started to have a series of products coming out on a fairly regular basis. So there was, it was all print, there was no television, certainly by this point at this point. But roughly once a month, there would be a new shoe in the pipeline that we would advertise.

The advertising was done first again by Carolyn, and then it became too much for her. She was just a freelancer, and we weren’t her only client. So she basically said she’d like to be replaced. So we brought in a couple of agencies. One only lasted for about a year, but the second one was John Brown and Partners. They were based in Seattle, and they started really doing the series of ads, a series of print ads.

And usually it was a fairly technical: “Shoe X is coming out and it does this, and here’s why you would want to run in it,” and blah, blah, blah. So they were informative, but they certainly didn’t have the Nike oomph, whatever you want to call it, yet.

And then that all changed in 1977. So one month in 1977, we didn’t have any new product in the pipeline. But we were particularly committed to running the ad. It was always in Runner’s World, I believe. And so we had a space there that we’d purchased. So Patsy Mest, who was the ad director at the time, or ad manager for Nike, told John Brown, “Just write something that makes a runner feel good about themselves.” That was I think the entire brief, at least that’s what John told me.

So he’s kicking around like, okay, okay, what would you do? What would you do? So he came upon a very simple, five-word: “There is no finish line.”

And then Denny Strickland, the art director for John Brown, and Bob Peterson, the photographer, had the brilliant idea to essentially create an atmosphere where you see a long way, a distance, in the distance there’s a runner running down a country road. So you can’t see the product. You wouldn’t know it’s Nike, literally, until you saw the bottom of the print ad. And that really became the first brand ad that Nike did. And it was mostly by the luck of the fact that we didn’t have product that month, and that John Brown had an inspiration, which is even more amazing because he told me he’s by far not a runner. Right? But he just felt like this was something that was like, to make them feel good, but it also meant like there is no finish line. So you ran a great race today, but tomorrow I bet you could do a little bit better because there is no finish line.

And it just hit. Right? I mean, people really, it resonated with them. We got letters, Nike got a bunch of letters from people saying how much they appreciated the fact that we see them, that Nike gets them as runners. And so it actually spawned such a demand that people started wanting us to make a poster of the print ad, which was not part of our plan at all. We didn’t have a poster business. But within three or four years, we had a multi-million dollar poster business because of that print ad that spawned other posters like “Iceman” and some of the iconic, “Supreme Court,” that are now super, super iconic. All came about because of responding to the consumer saying, “We really like that ad. It hits for us. Can you reprint it for us?”

Andrew Mitrak: So that ad, “There is no finish line,” great line, because there was no product that month. Most of the advertisements had been, “Here’s this shoe and technical specs,” and more advertising a product line versus advertising Nike as a brand and selling the dream. Did that, leading to things like the poster business, do you think that’s when it clicked for Phil Knight that advertising was really powerful? Or do you think that’s when he sort of went from being a skeptic to fully embracing advertising?

Scott Reames: Well, it’s funny because when I interviewed John Brown, he told me that he had introduced, Phil Knight introduced himself to John by saying not necessarily what he told Dan Wieden, “I’m Phil Knight and I don’t like advertising, I hate advertising,” but he said something along those lines, that he was skeptical. He felt that word-of-mouth or, as we used to say, “word-of-foot” advertising was best. An athlete, a runner, say, “Hey Andrew, I think you’d like this shoe.” And then that’s why you would run in it, not because you picked up a print ad or saw something on TV and you’re like, “I’m going to wear that shoe.”

So that was his mindset. And John believes that “There is no finish line” and the reaction to it was one of the first moments where Phil saw, literally firsthand, that there is a power to good advertising, to persuasive or not in-your-face advertising. But it was funny because that’s 1977, and then in 1980 or ‘81 is when Phil, I guess it was ‘82 when Phil first met Dan, and he said essentially the same thing, “I don’t like advertising.” So Phil was clearly reluctant or slow to embrace the power of advertising, which of course now is the ultimate irony, that it’s synonymous with Nike now.

But he needed to see it because in his mind, he’s an accountant by trade, he’s a runner himself. So for him, it was Steve Prefontaine wearing Nike running shoes that he felt was the power, the endorsement of that kind, as opposed to just a clever turn of a phrase or a funny, you know, words on a paper.

The Legend of Steve Prefontaine: Nike’s First Icon

Andrew Mitrak: Let’s talk about Steve Prefontaine, because it seems like he was one of the first Nike iconic sponsorships. Nike’s so well-known for partnering with athletes and having long-standing partnerships. Can you tell the story about their initial relationship with Pre and how this kind of became an early template for their sponsorships?

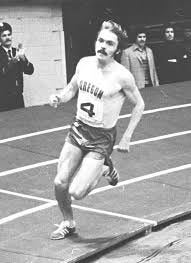

Scott Reames: Steve Prefontaine followed in the footsteps, literally, of other Oregon runners like Phil Knight of course earlier, but Geoff Hollister and Kenny Moore and some of the early 1960s runners, all of whom played important roles both either in the launch of Blue Ribbon Sports then Nike or in the University of Oregon’s ascension into essentially the elite of track and field programs.

So when Pre comes along in 1969, the Tiger Cortez had already been created, the Tiger Boston, I mean, we’re really starting to… we being both Tiger and Blue Ribbon Sports are really starting to get some, no pun intended, traction in the industry. Sorry, footwear jokes, what can you do?

And then serendipitously, this kid from Coos Bay, Oregon, a little tiny little town on the Oregon coast, shows up at the University of Oregon and he just instantly captures everyone’s… he was so magnetizing. I mean, people were just drawn to him. And he performed so well at Hayward Field. Right? That he drew from the crowd, and the crowd fed off him. It was just an amazing symbiotic relationship.

And he was also brash, but he backed it up. Right? He had swagger, but he was cocky, but he was also really good. So it’s not like he was just like, “God, that guy’s full of himself.” He was good and he knew it, but he then performed. And Phil seemed to really gravitate towards that personality. Maybe that’s Phil… Phil’s a very quiet, kind of introverted person. Maybe if he weren’t so introverted, maybe he would be more Prefontaine-esque, I don’t know. But Phil has referred to Steve Prefontaine as the soul of Nike on many occasions, which is all the more remarkable when you really look at that Steve had a very, had a very short life, unfortunately. He came to Oregon in ‘69 and he was killed in a car accident in 1975. So, and that was only two years after he graduated from U of O. And of course, back then, before NIL and all the other things we have today, Steve couldn’t accept any money from Blue Ribbon Sports. He was basically living on food stamps and surfing off couches for a while because he was training all the time. He couldn’t find a job.

So by the time he graduated, then he was able to, Blue Ribbon Sports could hire him to be an employee, if you will, but mostly to let him train. But it was only a two-year window where he was essentially affiliated officially with Blue Ribbon Sports. And yet he is so impactful that more than 50 years after his death, he’s still considered one of the triangle legs. I mean, Phil Knight, Bill Bowerman, and Steve Prefontaine are essentially considered the initial trinity of the company.

Andrew Mitrak: It’s a really remarkable story and a really sad ending to it. And I think when he died, he held like pretty much every record he could hold at the time. Is that right?

Scott Reames: He held, I believe, eight American records. And this was back when they were doing both mile and multiple miles, like one mile, two mile, three mile, but also the metric races too. And he held pretty much all of them from within about a mile to three miles, and then the metric equivalents, at the time of his death, which is remarkable.

Nike’s Pattern of Picking Rebels and Upsetters

Andrew Mitrak: It seems like a pattern is Nike, either deliberately or with a lot of luck, just finding the right talent to identify and pick the right talent early on and get their brand associated with them. And Pre is just one example, and of course, they’d have a lot of other examples of doing that as well.

Scott Reames: Well, theoretically, if a guy doesn’t or a woman doesn’t pan out, you kind of forget about them, right?

Andrew Mitrak: I guess that’s right. Yes, it’s survivorship bias. Exactly.

Scott Reames: Right. But so Steve Prefontaine passes in ‘75 and the mantle moves from—it doesn’t stay with running, it moves to tennis with a young John McEnroe, right? Well, look at McEnroe: rebel, brash, cocky, backs it up, you know, but not establishment, you know. And then the transfer is over to Andre Agassi: rebel, brash, you know, all the way up through Serena, Kobe. I mean, it’s just been the MO.

And this isn’t always true. I mean, Pete Sampras was a very successful Nike athlete and he’s pretty buttoned down. You know, he’s not, I don’t think you’d call him brash by any stretch of the imagination, but so I think part of it is Phil seems to just have a gift for identifying, especially when they’re young, right? Because it’s really easy to sign somebody after they’ve, you know, been with another brand for five years and you kind of know who they are.

Scott Reames: But to take a chance on a Tiger Woods, who, okay, yeah, obviously he was turned out to be great, but you don’t know that for sure when he’s 20 years old. I mean, there’s been a number of players that are can’t-miss who missed, right? And so, Phil does have—I don’t want to call it the Midas touch because he’s certainly not perfect. We’ve certainly had some people we picked that didn’t exactly pan out, but usually the ones that are, again, the status quo upsetters, the people that have a different point of view, the people that give zero F’s about, you know, how you feel about them. I mean, that kind of appeals I think to Phil, and it certainly has been some of the more successful Nike athletes over the years.

Andrew Mitrak: So we jumped a little in history.

Scott Reames: I tend to do that.

Andrew Mitrak: No, no, it’s great because it’s all—all these ideas are related.

The Serendipitous Origins of the Nike Name and Swoosh

Andrew Mitrak: And so, back to Blue Ribbon Sports becoming Nike. There are these stories that have been told a lot, and I don’t want to dwell on them too long. So there’s the story of Jeff Johnson coming up with the name Nike, and Carolyn Davidson designing the Swoosh logo for $35. And you can read about these in Shoe Dog, you can—they’re very well-documented online. I’ve also listened to several of your interviews to prep for this and I’ve heard you talk about it so much, so I don’t want to spend too much time on this part of the story.

But the thing that strikes me about this period of time is that it’s like lightning strikes twice in the same place at the same time. That that name, Nike, and that Swoosh that Carolyn designed, it’s like peanut butter and chocolate or something like that. It’s just like, wow, those go together so perfectly. And what do you attribute it to? How did luck happen like just like that, right there? Was it luck? Was it some marketing instincts? Was there something in the water in Beaverton, Oregon? Like, what happened?

Scott Reames: Well, Jeff has told the story multiple times, so I—and I don’t want to rehash what you said is already pretty much out there. But in terms of Nike was a chosen—it came to him for several reasons. Marketing was related to a big part of it. I mean, just the fact that it’s the Nike goddess of victory, the Greek goddess of victory. Well, certainly, again, like a blue ribbon, that’s kind of what you’d want to associate with, you know, victory. Duh.

The Marketing Logic Behind the ‘Nike’ Name

Scott Reames: But Jeff had also read quite a bit about the successful brands and what they share often. And usually it’s a one or two-syllable name. It’s a hard or exotic letter like a K or a Q or an X, you know. And I mean a couple of other factors, and he just was like, Nike, when he thought of it, it was just like, it’s like check, check, check, check. All those things seem to work. So he was really adamant that that that was the name.

And the funny thing was, just like with the Swoosh, all the people who were involved at the time with finally selecting the name Nike and the Swoosh logo agreed that they didn’t like either one of them that much. Both of them they considered to be the least gross, the least, you know, eh, you know. And that’s why that quote about Phil Knight saying, “It’s the one I, you know, I don’t love it, but maybe it’ll grow on me.”

So it wasn’t like, again, they were like the clouds parting and the angels singing and they were all like, “Ah, that’s the mark.” You know, it was more of, “Okay, well this will do for now.” So part of it was blood, sweat, and tears of developing the brand and developing the fact that Nike—the Swoosh was now standing for and being associated with quality and successful athletes. You know, so if it had been a circle or a—I mean, there’s a bunch of other drawings out there that may or may not be legit that Carolyn came up with. She didn’t unfortunately save the rest of them, I wish she would have.

So if it had been if it had been an X, let’s say, you know, then that today might be an X on a pair of shoes. You’d be like, “Oh, that’s the Nike Swoosh,” you know, or the Nike whatever, you know. And so we sort of again, retroactively look at now the Swoosh and say it was a genius move, or the name Nike was a genius move. But there were a lot of folks, when we first introduced the logo, especially the lowercase n-i-k-e, the italic lowercase Nike, a lot of people were like, “Who’s Mike?” Because the N looked like an M. And so there wasn’t that brand recognition.

And even again, Jeff Johnson, when he was at the first trade show in 1972 where we’re actually debuting the new Nike line of shoes like the Nike Cortez now. They they actually brought the Tiger Cortez and the Nike Cortez to Chicago to the NSGA show to sell them to retail clients. And Jeff Johnson basically said, “You don’t need this shoe. You’ve already got the Tiger, but we think it’s a good one.” And retailers actually said, “Well, we’re not sure what’s going on,” because we couldn’t talk about it. “We’re not sure what’s going on between you and Tiger that you would have your own brand. But you’ve always been straight with us, so we’ll buy some of your shoes too.”

You know, so it was literally, it was relationships, honestly, more than just explaining to them that, well, this Nike Cortez, it has, you know, Swoosh fiber, you know, or whatever. It was the relationships of it. And so if that’s—I don’t know if that’s marketing or if that’s just, that’s just building on your reputation and building on people trusting you.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, that’s right. So I framed the question in such a way that it’s as if lightning all struck in 1973 and everything came out perfectly and that everybody embraced this as an iconic brand from day one. And the truth, of course, is no, it takes time. Right? You build—by the way, did I have the year right? Is it 1973?

Scott Reames: ‘71.

Andrew Mitrak: ‘71. Okay, thanks for correcting me. Yeah. So those happened in 1971, but people are mispronouncing the name, calling it Mike. And it takes years and years of building the brand and identifying with that Swoosh that it becomes sort of ingrained with all this meaning. So it wasn’t that it was like a home run right off the bat. It did take a lot of time to build.

Scott Reames: It was unique enough, and it did look different, right? I mean, you got Adidas with three stripes, you’ve got Tiger with the sort of two-stripey, you know. And so stripes were kind of the look. And you could call the Swoosh—I mean the Swoosh originally was just called “the stripe,” right? It didn’t—nobody said, “This is the Swoosh.” In fact, we never have been able to fully find a paper trail or any sort of trail that went from “Swoosh fiber” for a shoe in ‘69 to “the Swoosh.” There was no memo saying, “Henceforth, this shall be called the Swoosh.” You know, it just sort of organically was referred to that over time, and then later trademarked.

So it was a different enough logo. And there was also other efforts to—I mean, so the Nike boxes were orange, right? The shoeboxes were orange, very bright orange to contrast with the blue boxes of Adidas, right? So you again, very different—we’re trying to find different ways to differentiate that this brand is clearly not that brand, you know, or the other brands. And that was done with some forethought. Jeff Johnson has told me that that was specifically done, the orange boxes and some motions, some movements were made to make us look and be remembered as different from the establishment.

Rob Strasser: From Lawyer to Nike’s Head of Marketing

Andrew Mitrak: I want to ask about another major figure in Nike’s marketing history, and that’s Rob Strasser. And Strasser, he joins as a lawyer initially, then he became Nike’s head of marketing. And this just seems like an odd transition. I can’t think of many great marketers that started as lawyers. So can you tell me about this early part of Rob Strasser at Nike?

Scott Reames: Yes, so he was one of—he was on the legal team. I mentioned earlier the lawsuit between Onitsuka and Blue Ribbon Sports. And he was on the working for the company, the law firm that Nike hired to represent them. And so he did such a great job and he just bonded. He bonded with Phil and some of the other Nike executives at the time. And so when the dust settled and the case had been won, at some point, I don’t know if he approached Phil or if Phil invited him, but he joined the company.

And I think he did join originally to do some partly legal work, but you know, again, in the 1970s, it was pretty much all hands on deck. And I don’t know, I don’t know if I’ve ever really heard the story of how he specifically was asked to become the marketing director. I know that it was with—they had what was called the Buttface meetings. And again, if you’ve read Shoe Dog, you know the Buttface meetings. So it was fairly common every six or nine months for the senior leaders to get together at an offsite and walk in as the marketing director or the apparel VP and walk out as the footwear VP or the, you know, so they they would basically do almost a carousel. So it could be that Rob walked in as the legal rep and walked out as the marketing director. I don’t know.

But whatever, however that came about, it was genius because he had an affinity for it. And that was what led to, you know, many, many—I mean, we talked about the poster program. I mean, that was essentially Rob’s realizing that this is a—that people want posters. Let’s make them posters. It’s not part of our business plan, but we can figure this out. Air Jordan. I mean, the whole signing of Jordan, that was Rob Strasser. And just the marketing in general, creating the Pro Club, you know, where people where NBA and ABA players got a percentage of some of the footwear that was sold that they wore. That was that was not done in the industry. And Rob created that. You know, so he was very much ahead of his time in a lot of things. Or maybe he just was a guy who could just analyze stuff. Maybe that was his legal brain that he could just say, “Well, this would make sense. Why don’t we do it this way?” And there’s a lot of more Wild Wild West back then.

The Story Behind Rob Strasser’s Legendary ‘10 Principles’

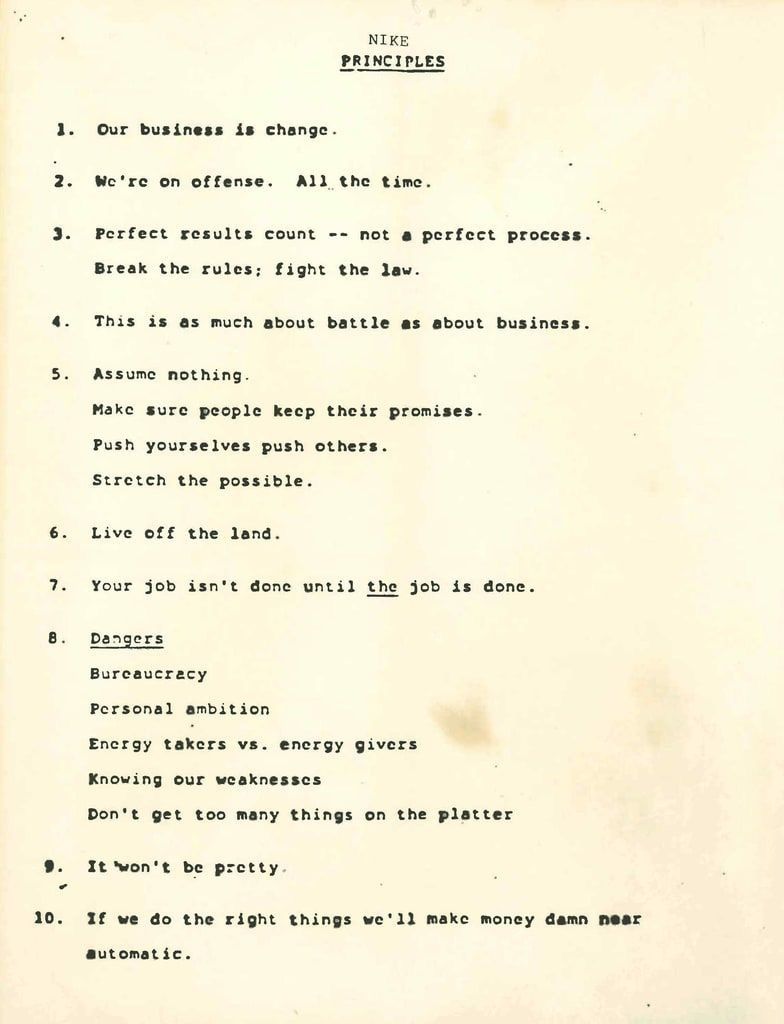

Andrew Mitrak: Rob Strasser, he penned these 10 principles. And we don’t need to read through all 10 of them or anything like that, but when did this happen? When did he write these principles? And what was sort of the context for that?

Scott Reames: It was 1977. And from what I’ve been told, because Rob has passed many, many years ago, so I never got a chance to interview him. But what I’ve been told by his secretary is that she was called at the time, and by others who knew him, was he was just having a bad day. He—I’ve heard different versions of it, but essentially a couple of employees were pushing back on being assigned something that they didn’t really want to do. And Rob, that was like the last straw for him, that the people were no longer fully embracing that we, you know, you give all for the company and you just do whatever’s asked.

So he went to his typewriter, sat down at his desk, just started quickly, quickly, quickly, you know, pounding out what became these 10 principles. Showed them to his secretary. She kind of looked at it like, “Oh, you sure you want to do this?” you know. And so they she made or they made a bunch of copies and he taped it or left it on people’s chairs or taped it on their doors if they weren’t there. Didn’t run it by Phil Knight, didn’t run it by anybody. It was just there the next morning when people showed up.

And even though—I don’t know if we want to go down that whole Air rabbit hole, but in the movie Air, they they play those up as if they were like on every wall and they were like the guiding principles that everybody quoted all the time. And that doesn’t seem to be accurate at all. But I can tell you that almost everybody I interviewed had their original copy. They never got rid of it, right? So it had an impact. Not an overt daily, you know, it wasn’t like, “Well, as principle number four says...” You know, there was not that kind of quotation of it.

But I think people appreciated that somebody, first off, clearly has a passion for it. And secondly, there’s the first effort to really try to figure out, well, what is it about our company that does make us different? And we’ve been, I mean, all the way through the maxims in 2001 and all the way to today with the five maxims now that there are, there’s been that desire to try to boil down to its essence what makes Nike Nike. And Rob’s was purely organic, purely hellfire and brimstone, you know, just and then they’ve done HR has tried to do a much more of a measured thing. And that’s to me, that was a little bit too shaved and polished, you know. So there’s but every time they do that, whoever does it, it comes down to performance, teamwork, authenticity, innovation. I mean, I’m pleased in a way that over 50, you know, 50-some-odd years almost later, the core values are roughly the same. However you want to articulate them, they’re really the same.

Breaking Down the ‘Break the Rules, Fight the Law’ Ethos

Andrew Mitrak: I’ll read through a few of them just to give listeners context. And I’ll also post a link to them in the blog that accompanies this show. But it’s:

Our business is change.

We’re on offense all the time.

Perfect results count, not a perfect process. Break the rules, fight the law.

And I’ll jump to number 10, which is: “If we do the right things, we’ll make money damn near automatic.”

And I do think, like you were saying how like when HR writes it, HR wouldn’t say “damn near automatic” or things like “break the rules.” They can’t say that. Break the law, like, oh, we can’t do that. Yeah. So, but it’s funny though, like you need to have a little edge to be inspiring, otherwise you kind of like roll your eyes at it. So, it sounds like they weren’t completely formalized, but they definitely landed and there were things people would remember and keep as well. So is that kind of how they were how they were used?

Scott Reames: I believe so. From the number of people I’ve talked to about it. And the hard thing or the thing that people need to be reminded of is the context of it. This is 1977. There was no guarantee that Nike was going to be Nike, right? I mean, we’d been only a company for five years as Nike. We didn’t have our own real basketball shoes at this point yet. We were mostly selling off-the-rack Blazers and Bruins that we got from, you know, different Japanese companies. So there wasn’t, other than the Waffle, the Waffle outsole, which was the one innovation that Bill Bowerman had brought in the mid-70s, when people, you know, people sometimes they laugh like, “Live off the land.” Like, yeah, like Nike has to live off the land or or, you know, “Break the rules,” you know, or it’s like they’re making it sound like we’re just, you know, we’re just kind of like completely just out there just to run roughshod on people. But we weren’t—we didn’t even know if we’re going to survive. There was some, ironically, since we’re dealing with tariffs today, there was some tariffs that were being imposed that were going to be costing the company like $25 million, which was like $24 million more than we had, right? And so it was going to potentially shut the entire company down.

This is all in the late 70s. So yeah, we’re Nike now and Nike’s, you know, multi-kajillion dollar business, but not in 1977. So this was this was very heartfelt and there was a real concern that if people did start to put themselves first or start to push back on being asked to what they do, that the company may not survive. So with that context, these 10 principles, I think, resonate more.

Andrew Mitrak: So you joined Nike in the early ‘90s, and this was after Strasser left, but shortly before he passed away.

Scott Reames: Correct.

Andrew Mitrak: Did you encounter these more like just in your role, or was it more later as a historian that you encountered them? What was when did you first come across these principles?

Scott Reames: I don’t remember specifically, but I don’t recall them being—I definitely would say it was probably after I created the historian role in 2005. If I had come across them, it might have been like, “Oh, that’s interesting.” But I didn’t really know the story behind it. Again, partly because there hadn’t been a me before me, right? There wasn’t a historian who was capturing this stuff and publishing it. So maybe the people who were around from ‘77 on who did keep them in their drawer or kept them on their wall or whatever, they may have known the story, but it was not like you could just go to the website or go, you know, it’s like, it was just like, “Oh, wow, okay. What was the context of this?” “Oh, yeah, Rob Strasser.” “Who?” “Well, he died last year.” You know, it’s like it was definitely not a cohesively told story. It was more of if you knew, you knew.

Setting the Record Straight on the Movie ‘Air’

Andrew Mitrak: Okay, going down the Air rabbit hole a little bit.

Scott Reames: Be careful.

Andrew Mitrak: I know, I know. So you had mentioned Strasser being instrumental in signing Michael Jordan and the Air Jordan and the Jordan brand. And the story is well-documented. Unfortunately, like the best-known documentation of it is the movie Air. And when I first saw the movie, I did like it. I thought it was like a very entertaining movie and all that. But of course, like later on, you realize, oh, it’s it’s like almost entirely a work of fiction aside from like a few, you know, yes, Michael Jordan and Nike worked together kind of stuff. So, but as a historian, are you are you just sick of being asked about this movie, or what’s your relation to it now?

Scott Reames: So I’ve had a little bit of a bell curve reaction to Air. Initially, I was like charged up. I’m like, I’m going to get the story straight. I’m going to tell the story the correct way. And I went on LinkedIn and, you know, posted a couple of links and stories. And then the next thing I know, I’m getting media inquiries. People are, you know, the Portland Monthly and Sports Business Journal want to talk to me about it. I was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, I wasn’t really planning to go that big.” But it was good because I was setting the record straight.

And then it became like, okay, now I’m telling this for like the 40th time. So I was getting a little tired of it. But now, I still feel that it’s important that the actual story be told because there are people in the movie who played a much larger role—Rob Strasser, Peter Moore—in the signing of Michael Jordan than did Sonny Vaccaro, who was played by Matt Damon. Part of that’s storytelling, I get it. I get creative license. But I know Rob Strasser’s daughter, right? I’ve worked with her. She works at Nike. I’ve met Peter Moore’s kids, his sons, you know. So it’s like, I want them, I want their families to get their due.

And you know, again, I just present what actually happened. If you—I thought the movie was actually pretty entertaining, too. Phil Knight actually told me he thought the movie was entertaining. When I asked him, because he had seen it before I had, and I said, “Well,” he said, “I thought they captured Nike in the 1984 time period perfectly.” And I said, “Oh, good.” I said, “How about accurately?” He goes, “Oh no, it wasn’t accurate at all.” I’m like... you know. So it’s just, that’s the hard part, is there are other people who were instrumental in signing Michael Jordan, and if you see the movie, you would have no idea.

The ‘Cringey’ Portrayal of Phil Knight in ‘Air’

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, for sure. So I’m kind of surprised that Phil Knight was able to enjoy it because from, you know, reading his book, seeing some of his his speeches, and, you know, you were describing him as a pretty introverted person, the Ben Affleck portrayal of him, he kind of comes off as a—I don’t know, not a great look. Not that I know Phil Knight at all, and you only get so much from watching interviews or watching a speech of his, but it didn’t seem to be anything like him whatsoever.

Scott Reames: The word that I was told and heard most often from people who know him and know the story was “cringey.”

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah.

Scott Reames: Right? That Ben played him kind of cringey or cringily because he’s not... I mean, again, in 1984, he was certainly younger, obviously, but yeah, there was just, it was a lot of license taken there. And again, I, my concern or my issue there is they could have reached out to Phil Knight, they could have reached out to me, they could have reached out to anybody, and they didn’t. You know, and again, as as people kept reminding me, it’s not a documentary, right? So it’s Hollywood.

But the hard part though, Andrew, after the movie was how many people treated it like it was a documentary and said things like, “Oh my gosh, Deloris Jordan, Michael’s mom, I love her. She’s tough as nails. The way she negotiated Michael’s contract...” and I’m like, “That never happened.” So that’s to me is like, you’re you’re basically taking David Falk, the agent, and basically minimalizing him and saying that it was Jordan’s mom that did it all. I’m like, well, that would be interesting and it’d be a great story if it were true, but it isn’t. So why would you write it that way?

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, for sure. And also, reading a bit about Rob Strasser, he seems like such a larger-than-life character.

Scott Reames: Literally.

Andrew Mitrak: Blustery and… yeah, exactly. And couldn’t be any more different than the Jason Bateman character. And it’s like, I kind of would like to… it seems like the real person would actually be a pretty cinematic character. Like, just would have a big screen presence. So I just wonder if you were to rewrite it or do a story like this, would he and Peter be among the main characters for you?

Scott Reames: Oh, absolutely. No, Rob Strasser—again, I didn’t meet him, but I’ve seen plenty of photos of him, I know plenty… I mean, his nickname was “Rolling Thunder.” He’s been described as a “walking HR violation,” right? I mean, the stuff that he would do in the ‘70s and ‘80s and the things he would say and the stuff he would throw at people, I mean, would get him written up by HR on almost a daily basis today. He was over three bills, right? So he was over 300 pounds, but I mean, it was a big man. It wasn’t like fat, he was just big. Very intimidating, very imposing.

So yeah, when I heard Jason Bateman, and I love Jason Bateman, he’s one of my favorite actors, but I was like, for what role? And then when I saw him, it’s like he’s witty and urbane and Jason Bateman. And Rob, from everything I’ve heard, was just… let it all just loose. He just was like, didn’t give… he just would be Rob. And so it was like, there’s a disconnect here. That was a little strange. But the movie… again, it does capture some of the great stories, it just credits the wrong people.

The Impact of ‘Air’ on Nike’s History

Andrew Mitrak: Do you think it’s… when it comes to interest in Nike history, do you think it’s a net positive or a net negative? Because on the one hand, you know, you’re… spent a lot of time as a corporate historian at Nike, and it’s near and dear to your heart, and you probably want more people interested in Nike history. So it’s probably good to get people to think about what happens behind the scenes and think more about the ads they see and the shoes they purchase and the brand they’re familiar with. But on the other hand, it’s obviously got so many things wrong that we just talked about. So it has to be super frustrating for you to hear these things repeated. But just on net, do you think it’s been a positive or a negative?

Scott Reames: I don’t think it was a negative thing. I think it could have been more. And again, I think the story is fascinating enough that it didn’t need to have a lot of the manipulation of it. But in terms of, did it redraw and draw in a new generation of people? I think absolutely. So I’m not regretting that it was made. I’m just wishing that they had tried a little harder to stick more towards the actual happenings because they’re just as interesting in my opinion.

But if it spurs other movies, if it spurs other people to become more interested in how Nike came about… I mean, Nike’s story is a fascinating story, right? I mean, to your point, you made a comment earlier about how there were many times that Nike has… you know, if you go left instead of right, you would have come to an end. It’s kind of like a video game, right? You pick the wrong door, game over. And when Phil and I were working, when Phil was writing Shoe Dog—I say Phil and I, but Phil wrote Shoe Dog and I helped to edit and helped with some materials—he was candid about how many times… I mean, we came up with more than 20 or 25 different times where, you know, if it’s left, it’s game over; if it’s right, we continue. And he just kept making the right calls, or the decisions just turned out to be the right ones. And that’s why we’re here today. There are so many other businesses that make that one wrong turn and they disappear, you never hear of them again.

How Wieden+Kennedy Landed Nike as Client #1

Andrew Mitrak: So around the time of signing Michael Jordan, it was in the early ‘80s that Nike formed its relationship with Wieden+Kennedy. Can you tell me about how they were founded and how Nike came to be their first client?

Scott Reames: Sure, that’s a great story. So we had, as I said earlier, bounced around. We had John Brown and Partners, before that we had the Morton agency—I forgot them. So we had Morton for like a year, John Brown and Partners for like three or four years. And there was another agency called the William Cain agency here in Portland. And they had a young copywriter named Dan Wieden. Dan Wieden had worked with Peter Moore at Georgia-Pacific before that. And as Dan said, “Peter left Georgia-Pacific, I got fired.” So they kind of went their separate way. Dan ends up at the William Cain agency, and Peter ends up at Nike.

So Peter is starting to need some more advertising help, and he contacts his old guy from the agency, Dan Wieden, or from Georgia-Pacific, and Dan starts writing some copy. And then Peter at some point decides he’s got too much on his own plate to do all the art direction, so he says, “Can we find somebody to do the art direction?” Well, David Kennedy was also an alum of Georgia-Pacific, and as Dave told me, he said, “I got tired of working on plywood advertising and decided it’d be more fun to work on footwear.”

So Dan and Dave individually—Wieden and Kennedy, not Wieden+Kennedy—started working on the Nike account to the point where they realized that they wanted to do this full-time on their own and not be working for another agency. So they made a pitch on St. Patrick’s Day, 1982. They made a pitch to Tom Carmody and Patsy Mest, who were the advertising people at Nike, that they would start their own agency and they wanted Nike to come along as their first client.

Again, this was one of those times where I just loved my job so much, because Dan, being a tremendous storyteller that he is, of course, can’t just say, “And so they signed us.” He’s giving me the whole thing about how he’d had a tooth pulled or he was about to have a tooth pulled, so he’s on painkillers. He’s already nervous about the meeting, so he’s having a drink or two. And he just said the whole thing is like this surreal circus going on in his head, and they’re pitching this idea of becoming the agency. And I said to him later, “What if they had said no?” And he goes, “Well, I probably would have quit and moved to Chicago or moved away.” But thankfully, Tom and Patsy decided that they would go with these two.

And on April 1st, like two weeks later, they officially opened up their doors, if you will, although the door was like a hotel, and they were using… they borrowed a card table and a typewriter from Patsy at Nike. And that was essentially the launch of Wieden+Kennedy on April 1st, April Fool’s Day, which I adore, 1982, with Nike as its only client. They had never done a national TV ad, Nike had never done a national TV ad, and by October, they did their first couple of ads, and then, well, you know the rest. It worked out pretty well.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, for sure. The rest is that, yeah, 40 years on, they’re still an agency partner for Nike. So it seems like amazing.

Scott Reames: Winning Emmy awards and doing all these cutting-edge, amazing things.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah. It’s funny also that Georgia-Pacific was like the common thread of so much talent because I don’t know, I guess I don’t mean to be offensive to any Georgia-Pacific fans out there, but it’s kind of the most boring company possible. It’s like, what, it makes like cardboard boxes or something like that, or like tissue paper or something. It’s kind of a funny… just a funny place for all this talent to spring from that would do such creative, iconic ads out of that company.

The Darkly Inspiring Origin of ‘Just Do It.’

Andrew Mitrak: I have to ask about the inspiration for “Just Do It.” It famously is… Dan Wieden credits this to Gary Gilmore’s last words, which… it’s sort of a dark story. There had been this moratorium on the death penalty, and then that gets overturned, and Gary Gilmore was the first to be executed in 10 years, and his last words were “Let’s do it.” His last words are “Let’s do it” in front of a firing squad.

And then 11 years later, Dan Wieden comes up with “Just do it” as a slogan for Nike, and he kind of recalls that it was Gary Gilmore’s “Let’s do it” that was the inspiration. And it just seems like a really odd connection. One that it’s not one-to-one, it’s “Let’s do it” versus “Just do it.” But also just that this odd little thing that’s a little footnote in history that’s kind of a morbid piece of history inspires, you know, probably among the best-known slogans in history, certainly in the top few. And it just seems like an odd connection. So what do you think about this story and what… is this truly how it happened or what’s your take on that?

Scott Reames: Well, all I can tell you is that’s what Dan told me. And I remember my jaw opened up a little bit, like, “What?” And I said, “I’d heard rumors of different things, but this...” And he said… and then I finally said, “Are you putting me on?” And he goes, “No, no.” And he relayed the whole thing. He said, if I remember correctly, it wasn’t right yet before the firing squad, but essentially they were coming to get him from his cell, and they were like, you know, “Do you have any last words?” and so on. And he was just kind of like, “Let’s do it.” You know, I mean, “Just stop, let’s just get this over with. Let’s do it.” And he said that just stayed with him, that defiance, right? I mean, literally, it’s like, “Yes, let’s send me to my death.” You know, it just attached into one of his synapses in his brain and it parked there. From what he told me, that’s kind of the way his brain worked. Things just stayed with him.

So why it was 11 years, I don’t know if his mind had been refreshed by an article that he’d read. He didn’t ever go into that level of explanation. But I know that he was frustrated that the campaign that they were working on was very disparate. It had about a half dozen different 30-second ads, and they were all interesting and kind of whimsical and funny, but there wasn’t really a thread that tied them together. And he even said to me, he goes, “I don’t… I’ve never been a tagline person. I’ve never been really one that considers that to be great moments in advertising.” But he said, “I felt like this needed it. It needed something to bring them together.” And that’s somehow that the “Let’s do it” bubbled up.

Originally it was going to be “Do it.” And he told me that that felt too bossy. “Do it! Do it!” So he thought “Just do it” softened it a little bit. Like, “You know, okay, you’ve been talking about this forever, Andrew, just do it,” right? “You’ve been saying you’re going to start running after work, just do it.” It’s a little bit less, “Do it!” And it obviously worked.

Andrew Mitrak: I mean, obviously it does. And it’s something where… well, one, back to the story, it just sounds like one of those things that’s like an internet urban legend or something like that. It kind of sounds like there’s just a ring of it that sounds like it’s a myth that’s debunked on Snopes somewhere. But in this case, it’s actually true, it actually happened.

Scott Reames: The man credited with it told me he did it. So I don’t know how you refute that.

Andrew Mitrak: No. And also, as you say, it’s like, okay, I have notes that have been tucked away for more than a decade, and I’m sure that him being the copywriter he is, he could do that too. So it makes sense, but it does, yeah, it turns into this amazing inspirational ad. It’s an inspirational slogan that you can remember. And like, sometimes I honestly say, like there are times in my life where I’ve probably been on the edge of something and just thought, “Oh, just do it.” And it probably got me over the edge to take some action. And who knows how many times that… probably a billion times in the world somebody’s made some decision kind of thinking, “Just do it.”

Scott Reames: The reaction they got almost immediately was, I mean, women saying, “I left my husband or my boyfriend because I was inspired to just do it.” And it’s like, whoa, that was not part of the brief. But that was… people internalize that to be whatever it meant to them. And I think that’s why it’s still resonates so many years later because people still have an internal need for motivation. Some people are very easy to get themselves out there and other people just need, “Hey, just do it. I know you can do it, just do it.”

Mars Blackmon and Michael Jordan: The Perfect Foil

Andrew Mitrak: One of the ad spots I want to ask you about are the early Spike Lee ads with Michael Jordan. Do you know how those came to be? Because they’re among, you know… Nike’s made so many in history that are great, but those are just some of my favorites.

Scott Reames: Well, the… Jim Riswold, right, a legend at Wieden+Kennedy, now passed away unfortunately not too long ago, somehow had the genius to realize that Michael Jordan needed a foil, right? Needed somebody to bounce off of and essentially to be the pitch person, whereas Michael then almost became the anti-pitch person. I mean, some of those original ads, I mean, literally Michael’s saying, “No, Mars, it’s not the shoes.” You know, I mean, it’s kind of weird or kind of bold for a company to say, “Our shoes actually will not make you Michael Jordan. But here’s Michael Jordan.”

So, you know, and obviously, it was again very organic because Spike Lee had created the… I think it was Do the Right Thing, I think it was the first movie where Mars Blackmon appears, and he’s wearing his Air Jordans. So that was not because Nike placed them or gave him shoes, he just… Spike Lee, slash Mars Blackmon loved the Air Jordan.

So that was that special sauce of Riswold and others just basically saying, “Hmm, these two could really play off each other.” And obviously, they did. And we recreated that to some extent with Little Penny and Penny Hardaway, right? So and Little Penny was from Chris Rock‘s voiceover. Same idea, right? An athlete who’s maybe not the most bold and outgoing person, so you pair them with a foil who is, right? And you get pretty much the same result.

So I think a lot of times when we do ads, we do them once or twice and then we move on to something else. And Spike Lee, the Mars Blackmon-Michael pairing, just seemed to have that special “it,” right? It was like it hit over and over again. So they found different ways to bring the two of them together all the way up until, you know, essentially when Michael retires for the first time, and then we actually… Mars comes back, you know. So it’s or and then when he plays baseball, you know. It was like literally Spike Lee was almost attached to the hip to Michael through those ads.

Andrew Mitrak: Well, then the other foil to Michael becomes Bugs Bunny with the “Hare Jordan” ads, and that becomes Space Jam, which is the other one I want to ask you about because that seems like such an innovative, kind of unlikely pairing as well.

Scott Reames: Yeah, and I don’t, I don’t know the actual impetus for what caused them… you know, who was it that sat down and said, “You know, what if Michael played a bunch of the Looney Tunes?” I would suspect Riswold, but I don’t know for sure. But it was just a… you know, it was kind of whimsical. It was a Super Bowl ad, right? So they knew that they were going to have a bigger audience and a more diverse audience than just football or basketball players. It’d be essentially a lot of people who’d be watching it. So you want an ad that maybe is more… draws more people in. And obviously, Looney Tunes, you know, certainly who doesn’t… who didn’t grow up with them and who doesn’t love them?

So the fact that it actually turned into a movie and then later a second movie and I think even a remake of the first movie just shows that whatever the thinking was, it was tapping into the right vein.

The Origins of Nike’s Corporate Historian Role

Andrew Mitrak: In the early 2000s, is that when you made your transition to becoming a corporate historian for Nike?

Scott Reames: 2004 into 2005, yeah.

Andrew Mitrak: How did that happen? What did that look like?

Scott Reames: Before that, I was in what was called Global Brand Communications. So my role specifically was to do the communications for senior-level leaders, including Phil Knight, Mark Parker, and others. And the more I facilitated those interviews, the more I listened to these guys talking about the early days of the company, the more I noticed that there were… let’s just call it variations. You know, “The Swoosh was $35,” “The Swoosh was $50,” “The Swoosh was $75.” Just little things, but I realized that because we were a very oral storytelling company, once a voice disappears, whether it’s Bill Bowerman dying in 1999 or Rob Strasser in 1993 or ‘94, those voices are gone, right? And if we aren’t capturing those stories better, we lose that amazing opportunity to really learn from them.

And I was learning also a lot, Andrew, that a lot of what we accepted as lore wasn’t necessarily true. It’s like the game of telephone, right? It shifts and it drifts and it gets embellished and it gets just changed over time. And for the most part, except for a couple of the exceptions I just listed, most of the original people were still around back in the early 2000s. So I didn’t need to ask somebody else what Frank Rudy was thinking when he came up with the Nike Air idea; we could just interview Frank Rudy. And so we did. We could talk to Jeff Johnson about the name Nike and how he came up with it because he was around, and thankfully still is.

So it was just more of kind of these ideas percolating together. In 2004, Phil Knight also announced, at least internally, that he was stepping down as the CEO. And again, as his PR person, I felt like, okay, well his legacy, his stories… we’ve got to make sure we capture these because who knows what… nobody knew at that time that he would still be pretty much be hanging around every day. But you didn’t know that for sure. And Jeff Johnson, right at that same time, had had a pretty bad stroke, which he’s recovered from, but it was a little bit of a shot across the bow. Geoff Hollister, employee number four, also a long-time contributor, was diagnosed with a cancer that eventually took his life a few years later. So mortality was essentially rearing its head right and left in the early 2000s, basically reinforcing my belief that we needed to capture these stories while we still could from the OGs.

So that all came together. I pitched it to Phil over lunch. He said, “Let me think about it,” and a couple of months later, I got a call from the head of the department that ran the archives department saying they got a head count approved for the historian role. “Do I want it?” And I said, “Yes. Yes, yes, yes.”

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, it sounds like a dream.

Scott Reames: It was a dream. I did it for 16 years until I retired.

Nike’s Secret Sauce: Passion Over Pedigree

Andrew Mitrak: I wanted to sort of wrap up with reflections on Nike and their marketing story, and one of the themes that comes to mind is people who aren’t trained marketers making some of the best marketing decisions of all time. That Phil Knight was really… he was an accountant, that was his background. And Rob Strasser was a lawyer, and Jeff Johnson, I am not sure what he was doing before marketing.

Scott Reames: He was a social worker in Los Angeles.

Andrew Mitrak: He was a social worker. And Carolyn was… Carolyn Davidson was really early in her career as a freelance graphic designer.

Scott Reames: She was a student at Portland State, yeah.

Andrew Mitrak: Still a student, yeah, still a student. And folks who just kind of have to learn and just have some instinct and do the right thing. And I’m guessing if you have any reflections on that, of just folks who aren’t necessarily trained in marketing, but still… I don’t know what it says about marketing, that you don’t have to be trained in it to make some of the best decisions ever in it. But what are your thoughts about that?

Scott Reames: Well, I think Phil has a knack for finding people who are greater than their role, or that they’re flexible or they’re inquisitive and they… they can look at a problem that may not be something they’re classically trained in, but they’re intelligent and observant. And especially if they have a passion for and an understanding of what Nike is or who Nike is, they can articulate that maybe in different ways, but they can look at something and say, “Well, I don’t know, I’m not really trained in marketing, but doesn’t it seem to you that we should do this?”

And I think the more, whether it’s the principles or the maxims, the different ways that Nike tries to get people to understand who we were/are, the more people are internalizing that and accepting it. And again, if they’re people who think beyond what’s laid out in front of them, they can somewhat extrapolate and essentially come up with an idea that maybe isn’t really something they were trained to do, but it just seems… “Well, that seems like a logical thing to do, doesn’t it? I mean, if this is Nike, shouldn’t we do this this way?” And I’m probably oversimplifying it, but it just can’t happen so often and be a happenstance, right?

I mean, we’ve had this weird track record of bringing people in who were building architects and become Tinker Hatfield. He was not hired to design Nike shoes. He was hired to design Nike buildings because he was an architect. But somehow, he made that leap. And the people within the company who gave him that latitude… they could have easily said, “You’re an architect, get out of here.” Instead, it was like, “Well, that actually is not a bad idea, Tinker. What can you go with that?” That’s kind of cool.

Andrew Mitrak: Super cool. No, I think it’s super inspiring. Scott, I’ve found this conversation super inspiring. For folks who want to learn more about Nike history and follow some of your work online, where would you point them?

Where to Find More Nike History

Scott Reames: To my LinkedIn page, I guess, would be the best place. I don’t do a lot of social media other than LinkedIn. I try not to just barf out stuff on a regular basis. I try to come up with something that’s topical or something that maybe is in the news, like Air. But I love hearing from people, and I love… I don’t really do an AMA kind of thing, ask me anything, but I love it when people do send a question, and I try to find the answer if I don’t know it. So if they want to find me on LinkedIn and follow me, I’d be happy to respond when I can. I will not tell you how to get a job at Nike because I haven’t applied there since 1992. But it is a great company and there are a lot of amazing stories about it.

And of course, read Shoe Dog. Definitely if you have any interest in Nike, please read Shoe Dog because it’s an amazing look at the company.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, Shoe Dog is just one of the best business books, business memoirs of all time. So thanks for your contribution to Shoe Dog as well, because it’s one of those few business books that I’ve reread and enjoyed a lot because it’s so good. So thanks for that. Well, yeah, Scott, thanks so much for this conversation. I really enjoyed it.

Scott Reames: Thank you, Andrew. I appreciate it.