A History of Marketing / Episode 19

This week I’m excited to be joined by Laura Ries, a leading marketing strategist, speaker, and bestselling author.

Laura is also the daughter of Al Ries (1926-2022), the legendary marketer who's best known for popularizing the concept of positioning, along with his partner and co-author, Jack Trout (1935-2017).

Laura and Al Ries co-founded RIES, the global positioning strategy & consulting firm and co-authored several books together including The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding, The Fall of Advertising and the Rise of PR, and The Origin of Brands.

We talk about all of this in our conversation, and we cover Laura Ries’s upcoming work “The Strategic Enemy,” which will hit bookshelves this fall.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Laura is a world-class speaker and strategist, and this conversation is full of useful marketing advice and case studies including:

Coors Beer and their missed opportunity to own the “Light Beer” category

The .Com Bubble (Pets.com & Webvan) and how massive advertising budgets couldn’t overcome weak credibility and a lack of positioning fundamentals

How The Gap successfully launched Old Navy to expand their market share without extending their brand

And much more

Now, here's my conversation with Laura Ries.

Note - I use an AI tool to transcribe the audio of my conversations to text. I check the output but it’s possible there are mistakes I missed. I have lightly edited parts of this transcript for clarity.

Laura Ries: Born into Marketing

Andrew Mitrak: Laura Ries, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Laura Ries: Well, thank you so much. It's a pleasure to be here.

Andrew Mitrak: I'm excited to have a conversation about positioning, branding, your amazing career as an author and marketing consultant. But to start, I want to ask about your background. How did you first become a marketer?

Laura Ries: Well, I was born into it, shall we say. I was the only child of my father's (Al Ries) second and forever marriage to my mom, Mary Lou. And at an early age, just sitting at the dinner table, what did we talk about? Marketing. My dad was a great teacher. He loved to tell stories, and I always loved the story. We'd always have this little TV with the bunny ears. We'd always watch MASH at dinner. My dad had served in Korea with the army, and so he loved the show, I loved the show, but the commercials were where he shined. He would talk about the ads and what the companies were doing right and wrong. And he talked to me and my mom as if we were adults, as if we were the CEOs of these companies, and we could actually change something.

But it was a great introduction and really got me excited about the whole industry and the business. And of course, when I was little, he took me to the office in Manhattan where he had an advertising agency for many, many years. And I just, I just soaked it all up, and it just seemed so interesting and cool.

And then later on, it wasn't until my teens, the “Positioning” book came out in 1981. And a few years later, I don't know why, but I picked it up, and I was like, "Let me just see this thing my dad apparently wrote." And that changed everything. The book, as many people know, is amazing, but it really tuned me in. It was written in such a clear and funny and interesting way. And from that day on, I just knew that's what I wanted to do with my life.

Andrew Mitrak: That's amazing. You grew up with it, and in middle school, you read "Positioning." I bet that's younger than the usual reader for "Positioning." So, this is your father, Al Ries. And you shared a portion of your upcoming book with me, "Strategic Enemy," and you have this beautiful afterword that's dedicated to your dad, Al Ries. And you describe watching MASH and seeing these commercials. Do you remember any specific commercials or critiques that he had that come to mind from that era?

How Coors Could have Owned the Light Beer Category

Laura Ries: Well, really, one of his most famous stories and the critique was about Coors. And during that time, my dad actually had some meetings with Coors where he flew out to Colorado. And he got to Colorado, and he went to a bar, and he was like, "Give me a local beer." And the bartender was like, "You mean a Colorado Kool-Aid?" My dad was like, "A what?"

Denver is the Mile High City. Coors was naturally a lighter beer. And that wasn't something most people knew. And so he would go on and on about this story. And he told them on multiple occasions, "Don't line extend." Miller Lite was making headway, Bud Light hadn't launched yet. "Be the original light beer without the 'light,' you know, in the name." And he was so passionate. He was like, "It would have been such a great success." And they didn't do it, and it crushed him. And he would tell the story over and over.

And I always like to say, when I was a teenager, I mean, you'd just like, "Oh, roll your eyes," like, "He's going to tell it again." And it's funny because he didn't repeat it because he forgot he told us. He did it to make a point that the more you repeat something, the more powerful, the more memorable, and even the more believable it is. So, he was a great storyteller in that regard. And so, I do remember many of those stories that he would tell over and over again.

Andrew Mitrak: It's so funny. When I picture Coors, I picture Coors Light in a way. That is what comes to mind. Why is that? They are a diluted brand because you're split across multiple things. They're most associated with light. They also try to capture this idea of cold, which is a funny idea too.

Laura Ries: Well, originally it was such a cult following. It was only in the, it was Rocky Mountain water, it was in the Rocky Mountains. I mean, there was a tremendous PR effort around it. Even Smokey and the Bandit, the whole movie was about bootlegging Coors across the country because you couldn't get it on the East Coast.

But they missed out on an important opportunity to not, while they were successful with Coors Light, what if it had just been Coors? What if Coors alone could dominate that new category of light beer? And again, it goes back to my new book, "Strategic Enemy," but the enemy would have been regular beer, right? Coors could have owned it. When you have your one name on two things, who's the enemy? Right? You can't say that your regular beer sucks or that your light beer is watered down. It puts you in a very precarious situation. So, when you do have a brand that stands for one thing, has a very specific enemy, your message can be so much more powerful.

Laura Ries’s Early Marketing Career

Andrew Mitrak: So, I'm going to go behind the scenes a little bit. In advance of recording this podcast, I sent my questions in advance. And I wanted to ask you if there were any other influences you had when it came to marketing. And it was beautiful that you said, "Nope, it was pretty much just my dad, Al Ries." And I'm wondering, did you ever take marketing courses, or were there ever other marketers who tried to teach you? Because I imagine if you grew up in a household with one of the best marketing teachers in the world, it would be, you'd be a tough student. So, did you have any encounters like that when it came to learning marketing from others?

Laura Ries: Well, there are so many stories. My first job out of college, I had an internship at TBWA Advertising, right there on Madison Avenue. And I was on the account team for Evian and later Woolite. And then later got a job there. I worked for a whole year there before going to work with my father. But it was very interesting during that time, and I had a lot of opinions and insights. And I did work with great people. Louise was my superior, and she was just, how she worked with clients, and many people at the agency. I met Bill Tragos and many of the bigwigs. The agency launched the Absolut campaign and so had a great history.

And it really was fun to be in the agency and to know what it was like to just be a low-level executive in that experience. But I had such aspirations. And what my dad was able to tell clients, I really liked that. I mean, when you're an agency, you have to be very careful, and you can't tell them exactly what you think. I mean, you're trying, you're trying to sell advertising, right? You're not necessarily selling the strategy. So, that's what I really learned. I didn't want to be in the position of selling advertising; I wanted to help companies figure out what to do.

Now, listen, at 22, I had no idea what I was doing. But I was spunky, and my dad was just so generous with his time. And so, I look back at my career with my father. We were, he passed at almost 96 years old, so tremendous longevity of his life. And he was working until the absolute very end. But in those decades, that first decade, I was just learning from him, right? Soaking it up. I was a young kid. I would go with him on every session, every speech, and it was just amazing.

And then, into that second decade, well, I have my own experience, and particularly I had a lot of insight into female-type of categories and new technologies that he was very willing to listen to me on. And then, in the last decade, really leading the company, and also really honoring him and his induction to the Marketing Hall of Fame, and allowing him to really work as much as he could. And he really enjoyed it. And so, it was so special. I mean, maybe he couldn't travel to every speech, but we would work on the slides together.

And one of the last memories. He had fallen and broken his hip, and things were going down. And he wanted me to give a presentation. And so I went over, he had worked on some of my Visual Hammer slides. And so, the family and I gathered around while my dad was in the hospital bed with a big TV, and I would do the slides, and he hammered me. He's like, "Slow down. You've got to wait, pause. Don't stumble through this." And it was, it was really magical because my whole life, he was always teaching me, guiding me. And I hold that, you carry that with you. I carry those, those feelings and those memories, but also now able to really, after so many years, have my own ideas. And that's really exciting too.

Andrew Mitrak: That's beautiful. That long collaboration between a father and daughter is really a special thing. And you mentioned that your father passed away a few years ago at almost 96 years old, so remarkable longevity.

How Ries & Trout Popularized Positioning

Andrew Mitrak: On your website, on ries.com, you pay tribute to the history of positioning and the history of Ries and your collaborations. And you tell the story of many of the major milestones that your father contributed to. So it's, it's great as somebody who's interested in marketing history, it's great that you're preserving and carrying on that history. And can you tell the story for listeners of how Al Ries and his collaborator Jack Trout first became interested in this idea of positioning? Because it wasn't, it wasn't really a household word within marketing at the time that they got started with it.

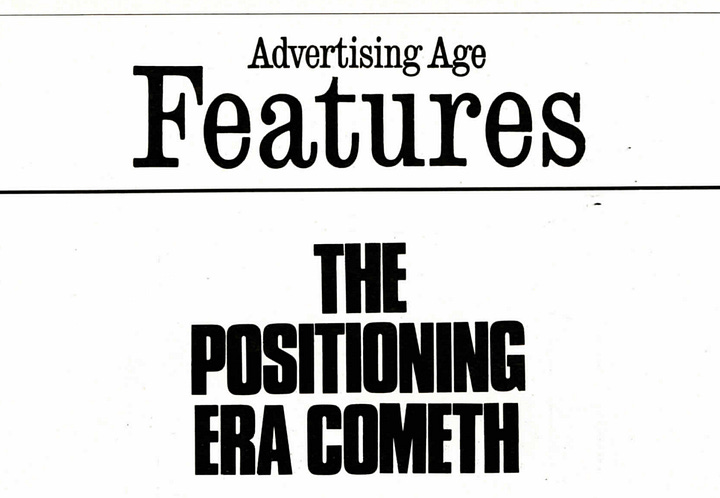

Laura Ries: No, not off the bat. And it is a great story. I mean, my dad was kind of one of the madmen of Madison Avenue, as was Jack Trout, in the 60s. And he worked in PR and at advertising agencies, and very early on, he struck out to start his own agency, Ries Cappiello Colwell, in 1963. And very exciting, but he was a young advertising company. They had mostly business-to-business clients. Jack later joined the agency. He was on Uniroyal, one of their clients, and then came over to the agency.

But the problem that they faced was, how do they build their agency, right? Unless you have big clients. And so they were trying to make a mark. And that's where the, the, the first idea of positioning came about, was how do we differentiate our agency? And it was at that time, the big word around Madison Avenue was David Ogilvy and creativity. And it was said creativity could do the job of 10 ads if you had one creative one. And the entire focus on the industry was over creativity. And while early on, they might be effective, and if you had a lot of money, but it wasn't for every company.

And so, what they thought about was, initially, the rational approach. And then my dad had the idea to call it "the rock." So, every ad had to have a rock. And what that rock was, was an indisputable idea, something that the mind wouldn't challenge. So, he was starting to get into the notion that it wasn't just what you're communicating, but the most important thing was getting in the mind. And so, to make it as easy as possible, again, most advertising today is puffery and claims, "We're the best this and the best that." Is that believable? No. When you say it, it's not believable at all.

But for one client, Uniroyal had the most patents ever, right? I mean, that was not disputable. People actually believed that. Or when you say, you don't do something, that's also very believable. So, this idea of the rock they kind of threw around, and it was actually Jack who said, "Why don't we call it positioning or a position?" And Al thought that was a great idea. So, they renamed it positioning and started writing articles and doing speeches.

And really, the big break was when my father was giving a speech where Rance Crain, the owner and editor of Advertising Age, the bible of the industry, especially back then, loved the speech. And he said, "Al, like, how about you write an article?" And my father was like, "Great." I mean, and in fact, it was a series of three articles. And that really blew everything up. And what did it do? It created a lot of controversy. All the creative people said, "What are these crazy positioning guys talking about?"

But that's what drives interest, that drives attention, and that drives the positioning idea into the mind. And it was this battle between positioning-focused approaches to marketing versus creative-only approaches. And I think positioning did a very good job along in that battle. And most companies today, that word "positioning" is used around the world. The book was successful not just here, but globally. And that's why my father and I have been to over 60 countries, because of the acceptance of the idea of positioning. And today, over 50 years later, the interest and importance of the idea that successful brands need to take into account positioning. It's not just innovation, but Peter Drucker said innovation and marketing, but I think it's positioning that is most important.

Positioning vs. Creativity: The Madison Avenue Debate

Andrew Mitrak: And there is a funny sort of meta story to that of them kind of drinking their own Kool-Aid and using positioning to position themselves against other advertising agencies to stand apart. So, just a lesson right there, to marketing yourself as a marketer. And so, you mentioned how when they published these articles, which by the way, are republished on your website ries.com, and it was great to read through them in the original format. But you mentioned how there was this industry response that was controversial. And do you recall any of the examples of the controversy around it?

Laura Ries: Yeah, I mean, it was tremendously controversial. To think back and luckily, my dad was very good at preserving things. So, we have many of the old articles that talked about the craziness. The creative community was really trying to defend that, but also, companies saw the opportunity of using positioning type approaches. And then many successful examples, right? Avis is number two because they try harder.

And many companies started to get in on this notion of, again, thinking about in the mind of the consumer, what's the open hole? What position can we occupy? And of course, the most important position to own is leadership of the category itself. And that led to many successful later books expanding on the notions of positioning.

How “Positioning” Shaped Marketing in the 1980s onward

Andrew Mitrak: So, they published these articles in the early 70s, and then in 1981, they published "Positioning," which is the book you mentioned earlier, is the book that you read in middle school. And it's called "Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind." And it became one of the...

Laura Ries: Right here!

Andrew Mitrak: You have it, you have it handy. Do you just have all the books handy right in front of you? That's amazing.

Laura Ries: Of course, I got all the books, I'm a marketing person! It still sells well. And I mean, obviously, many of the examples are old, but they still hold true of the principle of positioning. And very interesting to read.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, absolutely. The examples totally hold true, and there's, I certainly believe there's a lot of lessons in them. And if you were to describe the impact that it had on marketing as a practice, are there any examples that you'd cite of how marketing in the 80s and 90s, following the publication of this book, how it became really a different practice than it was prior to positioning being a key idea?

Laura Ries: It's funny. I did study marketing in some ways in college. I took a couple of classes. I was a communications major. And I did take an advertising class. And of course, I was very excited to get the book, the textbook, which my dad actually knew the guy that wrote the textbook. But there was a whole chapter on my father and Jack and positioning and everything. And I was so excited. I will say the professor was not too excited with me. But, he couldn't show favoritism or anything like that. But it was kind of very fun for me to see my father's name in that textbook.

And it changed everything, right? It made the textbook. I mean, how could you get more important than that? But really, it changed how people thought about marketing. I mean, it was really that, it was the communication going out was the focus of what do we want to say? Who are we? What do we want to tell people? And it flipped the script. And instead of thinking about it from just the, from us to them, is first to think of the mind. And what's in the mind today? And what will the mind accept? And is there a new category opportunity? And then thinking about things like line extension and how that impacts how the brand is thought of and stored and even talked about within the mind itself. I think there's been a lot more emphasis on the mind because of positioning when it comes to branding and companies. And so that's been so exciting.

But the other thing is that some people still violate them. We've written books on the immutable laws, right? And there, there are still many violations out there. So, it does keep the work exciting and important and shows that it's a challenge. Many of the things about marketing are not logical. We say that marketing isn't like math. In math, 1 + 1 always equals 2. In marketing, it's sometimes the opposite. 1 + 1 might equal a half, meaning the more things you expand, the weaker your brand becomes. And why 3 - 1 might equal 4. Because once you narrow the focus, you might have some, a much stronger message that you can promote, get attention for, create controversy. All of these things generate.

The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing

Andrew Mitrak: You mentioned those immutable laws, and one of the books that your father, Al Ries, published was "The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing." Can you share any background on the creation of this book?

Laura Ries: Well, yeah, I mean, again, I have the props here. Excellent book. Yeah, that was in the, what, was like 91, I think. But it was, it was simple. And part of their message in terms of what positioning was, is the more you can oversimplify an idea to make it short, simple, memorable, the better it will be received. And so, really, the goal of that book was to put these principles into little snippets, little short, 22 chapters of ideas that people could really remember, understand. It was a quick read. It definitely is again, one of their, their best books and best-selling books because it really does really pack a punch of, of really making those ideas super simple and super clear.

Andrew Mitrak: Do you happen to know, this is probably the only place where I've ever come across the word "immutable." I don't see it very often. It's just, but, do you remember how they came up with immutable and how they settled on 22?

Laura Ries: Well, I, I don't. I mean, they started working with HarperCollins. So, the original books were with McGraw Hill, and then Harper was a great partner. Al, and our, the books that I wrote with him were with Harper. We had a long relationship with them. And Adrian Zackheim was the editor, and he was just amazing. And they had a great collaboration. So, I imagine it was a back and forth. They wanted a shocking word. Again, the title and the cover are super important in books. And so, having some sort of word that wasn't usual, was really a big part of it.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, that's right. It's funny to see how you market marketing ideas as well and how they come up with a striking word like that that is just so ownable. And as you mentioned, there are other books you published that continue on this idea of 22 or 11 or, so those numbers...

Laura Ries: Yeah, well, and being different, right? I mean, when you use a word that is known but isn't used that frequently, it gets your attention. And so, books and ideas also have to be positioned. And names and visuals are incredibly important. So, we try to, and all, believe me, we've had many fights with publishers over the covers. And not all of them are our favorites, but we certainly have a few.

Building Ries & Ries: Father-Daughter Dynasty

Andrew Mitrak: Around the time that this book comes out in the early 90s is, is the same time that you founded Ries & Ries together with your, with your dad. And what was it like going into marketing consulting as a young professional and going into business with your dad?

Laura Ries: Well, I mean, it was, it was magical, honestly. It's funny, my dad always said, the most, after we started working together, the question he was asked most often after a meeting or presentation was, "How did you get your daughter to work with you?" You know, many successful entrepreneurs and business leaders are like, they wish their kids, especially their daughters, would come work for them. And the answer was, I never, I never pushed it. My dad never asked. It was, it was almost, it was unspoken. It was just a feeling between us. And I think the fact of when you tell a kid to do something, the last thing they do will be what you tell them to do. So, he definitely took that advice and didn't try to push it. But what he did was just so remarkable. And also his just willingness to teach me and not try to pretend like he was a big superstar, and just sit down with me.

I mean, I have so many memories of working together, especially on projects. So, as young as the fifth grade, I was bringing my own slide projector to the class presentation, which I always joke, I mean, the other kids did think I was weird, but I always like to say I was practicing for my future. And he took an enormous amount of time to help me. And with those projects, I really learned how to break down ideas, how to visualize them, how to simplify them. So, whatever the topic was, it wasn't really about the topic, it was about learning how to present. And I mean, honestly, I just, I mean, I had a, I like to present, as you can maybe see. I don't mind being on camera. I love talking about ideas. And so it turned out to be a great fit.

Andrew Mitrak: I think the first book that you published together was "The 11 Immutable Laws of Branding on the Net."

Laura Ries: No, 22. Yeah, we did the 22 first.

Andrew Mitrak: You did 22. Okay, so was this "Branding on the Net" or was this...? (*Note to readers: My research was wrong here, and this is why you can’t trust everything you read on the internet!)

The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding

Laura Ries: This was, yeah, this was the book, "The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding." And so, I started working with my dad in '93. Actually, the marketing one was in the late 80s, and then they had "Horse Sense." And then, I started working with him in '93. So, I helped him with the research on the book "Focus," which is another one of his really big, important books. It really breaks down the importance and as well as the impact on a company's financials of when you, when you focus a corporation. So, I was there and saw the whole process with him, and it was super exciting. And then we pitched the idea for the, the "22 Immutable Laws of Branding," which also the publisher was interested in exploring into, branding was becoming a big, a big and bigger buzzword.

So, yes, so we worked together on that. And again, he was so generous to make me a co-author and allow me to participate in that. But it was super fun, just you have to work out all the chapters and the order and the examples and the research, which was much harder to do back then. I mean, we subscribed to probably 30, 40 magazines and newspapers, constantly, we had to rip them out and save them in folders. It's so much easier today with being able to use the internet to find this stuff. But he was very diligent about saving and reading. And that's really an incredibly important part of our process, is studying the case histories. So of course, we've worked on a couple hundred brands, but we've studied thousands and thousands more by reading their case histories of what made them successful. I think that's the most important thing for marketing, of how they get that brand in the mind? That's the big challenge. And it's very difficult, but once it's done, it's very powerful.

Early Internet Marketing: Branding on the Net

Andrew Mitrak: I didn't think about that. Researching these books and coming up with these case studies prior to the internet would have been so difficult. And you were coming up in your marketing career, building, building the consultancy, Ries & Ries, at this time as the internet was developing. And it sounds like you kind of extended that idea of the Immutable Laws of Branding to the idea of 11 Immutable Laws of Branding on the Net. And were you on...

Laura Ries: The net came up and the publisher was like, "You've got to write something." So, I mean, we wrote that book really early on. I mean, it was right at the we probably were writing it in '99. You know, honestly, we did a pretty good job. I mean, not everything is accurate. I think we underestimated the power of search because we thought people would go right to websites. But the opportunity to find information once everything was on the internet became a truly big deal. But I think it's really important and our biggest message with that internet book, and it's the same with any brand, but there was the, the .com bubble was all about people wanting to use generic brand names. So, it was books.com or pets.com or business.com, which were going for millions and millions of dollars. And what we said was, "No, it's going to be brands. It's going to be Amazon, and it's going to be brands that are built for the internet."

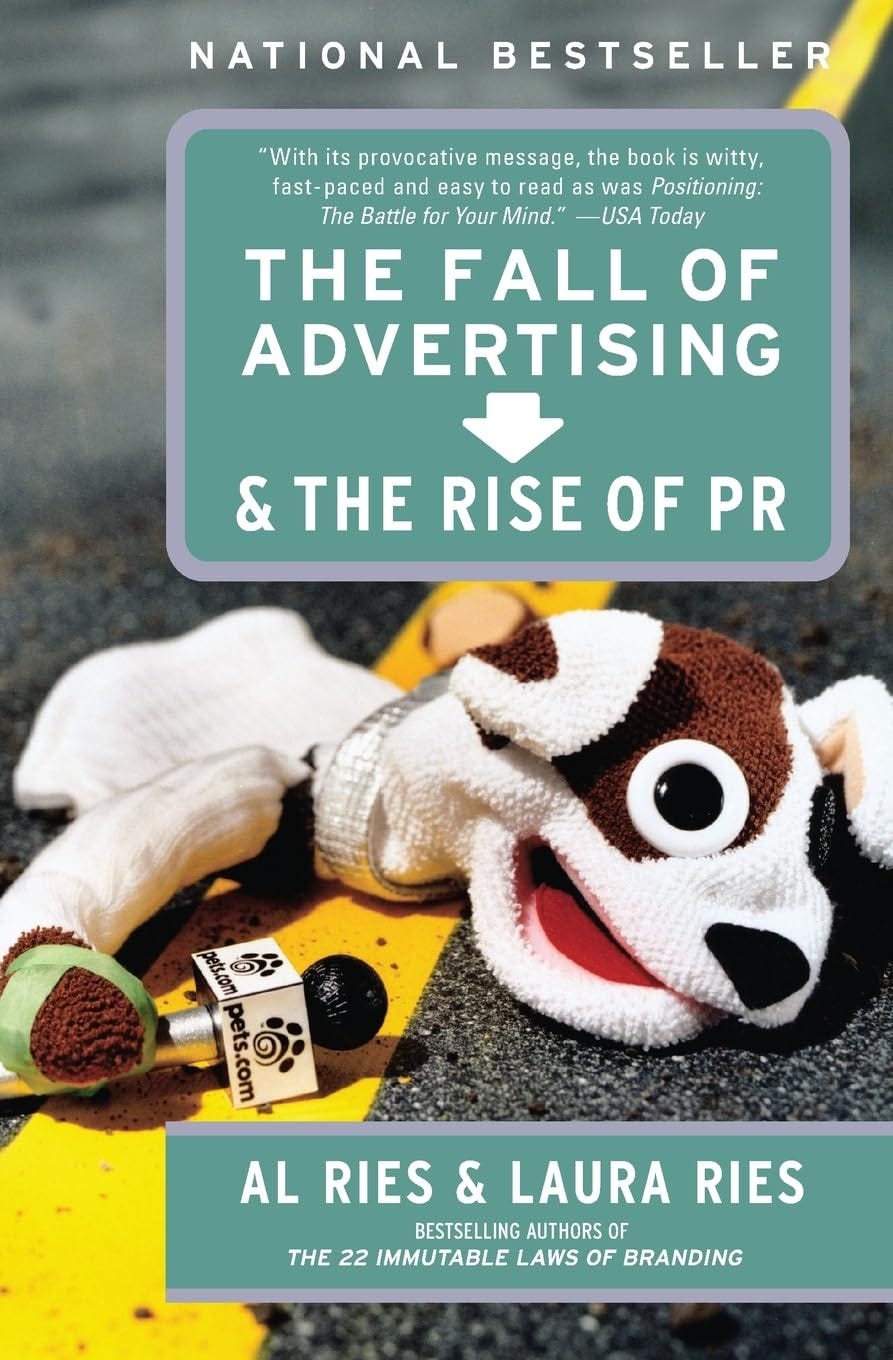

And also, then subsequently, in combination with that, was the importance of PR and not starting with advertising. Because while Webvan wasn't a generic name, they started with massive amounts of advertising and quickly went belly up. And of course, as you know, the cover of the "Fall of Advertising" book is the demolishing of the pets.com sock puppet, which really was the poster child of that era of using $50,000 in $50 million of advertising to launch a brand that had essentially no sales. Not good math. And instead, you have to have a obviously the right name, the right brand, and business strategy, but then using PR to gain credibility and allow it to go along with the rise of the company itself.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, it's funny how these things come in cycles because then over the last few years, we saw a big rush to the .ai domain name and a lot of generic brands using just “something.ai” as their thing. And you just got to, got to learn the lessons of the previous era before you make the same mistakes all over again.

Laura Ries: I know, and it's funny. I mean, history repeats itself. If you don't study history, you may be condemned to repeat it. I mean, it went back to Miller Lite. The original brand name was L-I-T-E. They tried to make it a new brand for a new category. But L-I-T-E is, it looks cute on a piece of paper, but how do things process in the brain? It's sound. And the sound is the same whether it's L-I-T-E or L-I-G-H-T. And that was a critical difference. And many companies today continue to even make that difference. I mean, Freshpet dog food, if you ask people, "Do you buy Freshpet?" I say, "Yep, I do. I ordered Farmer's Dog." Because that's a real brand name. You need both. You need a category name, and then you also will benefit from having a real brand name, one that has a capital letter.

The Fall of Advertising and the Rise of PR

Andrew Mitrak: Over this course, there was, there was "Positioning," there was "The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing." You co-authored "The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding," so you kind of extended your marketing consultancy beyond just positioning to also doing branding. And then you write "The Fall of Advertising and the Rise of PR," which you were just alluding to, and it has this hilarious pets.com sock puppet deflated on the road.

Laura Ries: I mean, if you haven't seen it, people have to see it. It's the best. Yes.

Andrew Mitrak: It's great. What was it like kind of expanding the scope of your purview when it came to marketing consulting to, to be in branding, in PR as well? What did that look like for you as a professional?

Laura Ries: First of all, we made a lot of friends in PR. I will say that.

It is an interesting trajectory in terms of, my father ran an advertising agency, which is Ries Cappiello Colwell, then that was later in the late 70s named to Trout & Ries. But for 30 years, they were an advertising agency. And with the rise of positioning, however, they got attention from many big companies, as a matter of fact, even like Burger King hired them for strategy. And Burger King didn't want this little agency to do advertising for them. But positioning brought in clients for consulting. And so, by the 80s, the business was really half and half. So, they had half traditional advertising agency. They had 200 people in the Manhattan office. And then half of it was these kind of consulting projects. And they were, people are busy, they just do what they do, right? They were running around.

But my dad was giving a speech in the 80s on positioning and on focus and all these important things, and the danger of line extension. And some fella in the audience raised his hand, his question was, "Why don't you follow your own advice? You're advertising and consulting." And my dad was like, "Hmm, you're right. You're absolutely right." But it was scary to lose what, half their revenue? I mean, that's incredibly scary, but they did it. So, the decision was, we're going to get out of advertising. We're only going to do what really made us world famous, which was positioning strategy. So, they took two years to shut down, wind down the agency, and he and Jack came in, I think '88, just strategy consultants. They had an office in Greenwich, Connecticut, out outside of the city to kind of make that distinction, and were just consultants. And that was one of the best things he ever did.

The second best was, of course, working with me. Which was really fun. But it really was very, very important. So, it was then a decade of being in consulting and not in the ad agency business that we did write the book on PR. And all of the books essentially come from the experience working with clients where noticing what does work, what is happening, the downfall of companies that used massive advertising, most associated with a line extension, right? Companies choosing that route instead of new brands and seeing how things even as Botox was one of our great examples because it was not allowed to be advertised because it was an off-label usage of the drug. They had to use PR. And guess what? It became a multi, hundreds of million dollar product because of the massive amounts of PR and why nobody in America can frown anymore, or anywhere around the world because of Botox. So, it was examples like those. And of course, many others. I mean, Starbucks didn't advertise for 20 years, yet has built one of the best, most known global brands around the world.

The funny story about "The Fall of Advertising," the initial name, because remember, a book title should be shocking. Listen, the immutable laws, I mean, sometimes companies can break them and be successful, but the name is shocking. You have to be shocking. So, the original name was "The Death of Advertising" or "The End of Advertising" or "The Death." I think it was “the death.” Yeah, we had a, our Rest in Peace. And we sent it, of course, Rance Crain became a very good friend of my father's. And he sent Rance a cover and a summary. And Rance said, "Al, you can't call it 'The Death of Advertising.' We can't write about it. Our magazine's called 'Advertising Age.' Can you tone it down a little?" And that's where we changed it to be "The Fall of Advertising." And it was literally one of the best moves we made because it, listen, the book didn't say that advertising was going to be over. It says that advertising is best used when a brand is established in the mind. It's necessary to reinforce a position. What should Starbucks do today? Massive advertising is what they should do. And they are making steps in that direction and have turned up the, you got to defend your leadership. Advertising is a defensive mechanism to keep, keep Dunkin' Donuts from getting too much attention, right? You got to hammer in what it is that Starbucks stands for. And that's coffee, and that's baristas, and that's the back to Starbucks strategy is trying to do that, go right back to what they focus on: coffee.

Are Marketing “Laws” Breakable?

Andrew Mitrak: Something you mentioned there is that you have these 22 immutable laws, but people can break them and still be successful. When you author a book that has these laws, do you get sick of people asking "but what about" type questions?

Because of course, they're general principles, general guidance, right in most scenarios. But do you, do you kind of find that coming up a lot whenever you make a statement like this is a law?

Laura Ries: Yes! But first of all, marketing is not like physics. Right? In physics, if there's one situation, and the whole law of gravity is gone, right? It doesn't work. In marketing, that's not true. I mean, yes, you can always find some company that violates the rules and still has some success.

But what we have found, and where positioning had that very much in the 80s where people would say, "What about the Japanese, Al? What about GE, Al? GE puts their name on everything. Sony puts their name on everything." And at the time, his answer was, "Let's wait and see. I don't think it's long-term, the right strategy." Short-term, line extension can be successful. It's the long-term that it catches up with you.

And look at GE, and IBM, and Sears, and Sony that have been undermined by their line extension strategy and the one name on everything strategy, as opposed to, say, Apple. Apple is the company, but they have a different brand name for each category, right? It was the Macintosh, it was the iPad, it was the iPhone. And so, that strategy long-term has been very successful.

But also, the key in presentations, where you've got a Q&A at the end, we always try to loop in those ones we know we're going to get asked about. And so, we will talk about the GE strategy and why it may have worked initially, but long-term, and not successful. Again, when a company is 100 years old, it's a little different than you as a startup. You know, you can't be GE. You can't be Amazon. You have to be who you are.

The other example we used to get asked about was Virgin and Richard Branson. And we got a great answer for that one. I mean, Richard Branson is a master of PR. He will dress in drag, he will show up in his underwear. He will do anything. Now, if your CEO will do this, well, then go ahead. But also, the numbers don't prove the success. They have not been successful in Virgin Cola, Virgin Vodka, Virgin wedding dresses, many of the crazy line extensions that they've gotten into. That short-term PR bump, long-term has not led to any sales.

Andrew Mitrak: Bless them for trying. It's a really entertaining company and enjoyable to watch. But he's...

Laura Ries: There's only a few of those kinds of people in the world. And listen, that's the, that's the key of positioning. Do you want to use the strategy that works 95% of the time? Or pin your hopes on being the exception? Pin your hopes on all of your competitors line extending, or your CEO is Richard Branson and able to get in the news every day. I mean, those are few and far between. Much better to have the right positioning, the right name, the right visual, will help you out much better.

The Origin of Brands

Andrew Mitrak: You mentioned marketing is not physics, but you did write a book that ties branding to evolution a bit. It's "The Origin of Brands," kind of tying to "The Origin of Species." And can you share about that idea of how brands evolve and what your approach to telling the story and evolution of brands was?

Laura Ries: That is a great book. We wanted more of the tree effect on the cover to represent the idea of what Darwin talked about. And that was really the divergence of species, of what he noticed was one species over time became multiple, and those were very different from one another. I mean, and so what we see is, it's not really the divergence of, of brands, but it's the divergence of the categories themselves, leaving opportunity for new brands to establish themselves. So, for example, in computers, what was a computer? Well, initially, that one tree was a mainframe computer, and IBM was the brand that got in the mind and owned the mainframe computer. And IBM said, "Terrific, that's our tree." But the thing happens is that that one category, computers, diverged over time and became mini computers, and then you had the software for computers, and you had personal computers, right? And palm computers. And what did IBM do?

Well, they said, "That's our tree. We're going to put our IBM name on everything." Instead, they faced focused competitors that looked at every new branch on that tree and said, "I'm going to be Microsoft and focus on software," right? "I'm going to be Sun and focus on workstations. I'm going to be Dell and focus on personal computers." And those were the big winners. And that's exciting because it means there's always opportunity to beat even a company as big and as powerful as IBM, but not by copying them, but by looking for a new category opportunity.

The big thing is that, and you know, funny to say it from someone who's lived their life in branding, people don't care about brands. They don't care. They care about categories.

Now, the tricky thing is, they speak in brands. They think Red Bull is a great brand because it represents the energy drink category in the mind. And the energy drink is where the power is, and they were the pioneer of that new category and being the leader, being the pioneer is the most powerful position you can own. Now, there's also the opportunity, again, in that category, to be a number two brand. And sometimes the number two can even overtake the leader. But Monster did just that by being different, right? The 16-ounce can with the, with the name that communicated that, with the visual and the green and the monster truck things and everything else that goes along with it. In many markets, Monster sells more than Red Bull, which is a tremendous feat.

Why “Positioning” Endures

Andrew Mitrak: I'm thinking about positioning that your father helped popularize more than 50 years ago. And if I think of all the buzzwords that have kind of come and gone, I could do a whole podcast about a lot of just those because there's so many, so many things that have come and gone. But positioning has this, this staying power. And I'm wondering, what's, what's your take on why that is? It seems like positioning's only gotten more important over the years. Why is that?

Laura Ries: Well, I mean, it works. I mean, I think that's part of it. But it's also strategy versus tactics. So, many types of these buzzwords are tactical oriented, and tactics change all the time. I mean, we've seen the introduction in our lifetimes about the internet and social media, and now we have AI. And those are tactically where this is strategic. And it goes down to really just the fundamentals of the mind. And the mind doesn't change. I mean, we are all human. We continue to be human. And while our experiences may have changed, building your brand in the mind is the end goal. And positioning explains how that happens. It explains how to deal with competition, how to position whether you're first in a new category or you're competing against a competitor where you're trying, or you need to start a new category. And it deals with the importance of the brand name and the category name. It takes into effect so many different things. And again, it was first, right? So, it went up at a time where people weren't thinking in that direction. They were thinking about communication as the main emphasis of marketing and primarily using advertising.

Positioning took the tactical side out of it and said, "Let's take it back to the fundamentals." And when you're the pioneer, that's a very strong position to have. And so, I think that that's also helped. But it's a great joy and it certainly brought my dad great joy to see that it was impactful. And his greatest hope was to help people. It really wasn't driven by money or fame; it was to work with companies, work with people. He loved to mentor people. People are brands. And that was tremendously important. I mean, listen, it was a very, my mother-in-law hates to hear it, but I did not take my husband's name, which back in my day was very unusual. But Ries was my brand, and I wasn't going to change my name to Brown. Most people don't think of themselves as a brand in that way, and they, they actually try to, "I'm going to just try harder. You know, I'm, I'm Laura Brown, and I should be just as successful." But you know what? I wouldn't have been. What my brand name was incredibly important, and it hasn't impacted psychologically in the mind to introduce someone, to get you through doors. And you should never overlook that. And don't throw away an opportunity to work with my father was, was one of those great opportunities. And so glad I took advantage of it.

Advice for Building a Father-Daugher Marketing Business

Andrew Mitrak: On that topic, on the Ries brand name and your collaboration with your father, I just think it's such a beautiful thing that you went into business with your dad. And we spend so much of our life at work, but really, obviously, the time that matters most is the time we spend with our family. And you just got to spend more of it with your dad, and he got to spend more with you. I have, I have two daughters. I'm expecting my third. Do you have any advice on how to successfully work with a family member or with a, I'd love for them to, I guess the Mitrak marketing family down the line someday, maybe. But, how can I make this happen? Or what's your, what's your advice on that?

Laura Ries: Well, obviously, I mean, if you are a parent like, telling your kids to eat their vegetables every day is unlikely to be successful. So, but being a role model, eating your vegetables and showing them the way, making it fun, making it entertaining. And spending time with them. As a busy as a young parent, it's so hard. But that time is so well spent. They will remember it. And I think that's what led me to, to want to work with him, to seeing the time he spent with me helping me on papers or projects, and and finding what it really is. I mean, listen, not every kid is going to be interested in what their parent does. But they, they, so you may find what they're interested in and learn more about it and participate in that way, or it could be that they have a genuine interest in what you do. And bringing them along. I don't know how much they're, my kids didn't really have like, "Take Your Kid to Work Day." I don't, that's, that was most one of my favorite things to do. And I think my parent, my dad would like pull me out of school, or there would be a holiday. And getting to watch your kid or getting to watch your parent. And most kids are they have to be entertained. Well, maybe not.

I learned a lot just sitting there bored sometimes at his office and wandering around the halls. And but all of those experiences are, I think, really make a difference. And so, trying to, trying to make that time and just enjoy your kids. I think it, they're such a gift. They are such a gift. And they're each individual and they're each different. But having the time to, to be with them. And for me, what was so interesting, obviously, I spent my whole life with my father, but those first 20 years, I only saw him at night, right? So, he was the dad, and he was traveling, and I saw him in dad mode. But getting to see him every day at work mode was really cool. And that is, was whatever you do, like if you can invite your kids to watch what you do, I think that's really so interesting. It gives them an insight into the world of what it's really like. It's not what the Netflix show tells you it's like. And that's, that's really the opportunity to see and travel is, is incredible.

The Strategic Enemy: Coming This Fall

Andrew Mitrak: "The Strategic Enemy" is your new book. It's slated for release this fall. I've seen a little preview of it. I'm so excited to read the full thing. What are you able to share about it with listeners?

Laura Ries: Oh, well, I am super excited. And the story of why I really wanted to write it is that's how "Positioning" was born, right? We talked about it already. I mean, they, they, it's not that they hated creativity, but they said, "We've got to pick an enemy to go up against." And to get your idea in the mind, you have to kind of reposition another idea. So, "Strategic Enemy," I think every brand should think about what that is. It might be a company, it might be a category, it might be another idea. But finding that enemy and positioning against it. And some tips like, "Just say no."

Many companies are built on this idea of just saying no. I mean, Salesforce and "no software." Chick-fil-A, right? "Eat mor chikin."

I mean, think about the power of saying no and how few companies really do. And don't be your own worst enemy. I mean, Coca-Cola launching Coca-Cola Life? I mean, what does that say about Coke? That it's death? I mean, that's the instant idea most people think of. I mean, don't do that. The line extension truly is the enemy of positioning today. That is what undermines the ability to own a position first and foremost. And listen, it doesn't limit you either, because you can launch your own enemy.

I mean, what's the best thing the Gap did? It was launching Old Navy. And ultimately, it competed against them. But Old Navy became bigger and powerful and the major force of the company itself.

So, launching new brands, like, for example, Mike's Hard Lemonade. What did they do? They launched White Claw. I mean, just one of the biggest beverage brands billions and billions of dollars. I mean, there are great opportunities, but if you take a moment to say, "Not how, what more can we get into, but is there a new brand that can even potentially become our own enemy?"

So, there's lots of great case studies, great ideas and inspiration to think about how you can utilize this, even when it comes to something like a nonprofit, the idea of narrowing the focus is extremely important. And you see the success of, for example, Tunnel to Towers. They're not just trying to help veterans. What do they do? Mortgage-free homes for heroes. You know, why don't, being burdened with the mortgage, not having the home be adaptable and smart. I mean, that's a powerful idea that evokes a visual, it evokes emotion, and it evokes the enemy of, "We can't let our heroes being straddled with mortgages, not being in smart homes." I mean, that lends yourself to having a great conversation.

Andrew Mitrak: That's right. So, "The Strategic Enemy," look for it on bookshelves this fall. I'm so excited to read it. Laura, I really enjoyed this conversation so much. As one last question, where can listeners find you online to follow your work?

Laura Ries: Well, that is simple. It is ries.com because I bought the URL in 1996 at the dawn of the internet. Working on, I've been updating the website, so looking at all the iterations over the years, it's crazy. And yes, the book, you can pre-order now on Amazon. Super, super excited to just share my passion about positioning and helping companies build better brands for the future.

Andrew Mitrak: Great. Laura, thank you so much. I've really enjoyed the conversation.

Laura Ries: Absolutely, my pleasure.