A History of Marketing / Episode 20

This week, I'm thrilled to be joined by Richard S. Tedlow, the MBA Class of 1949 Professor of Business Administration Emeritus at the Harvard Business School. Professor Tedlow is a renowned specialist in the history of business, an acclaimed author, and a truly engaging storyteller. Tedlow also the author behind the popular Substack, Dystopias and Demagogues.

After dedicating over three decades to teaching and research at Harvard, he was recruited by Apple to become a member of Apple University, the company's prestigious executive education arm, further cementing his expertise at the intersection of historical trends and modern business practice.

Professor Tedlow is the author of several excellent business history books and biographies. Much of our conversation centers around his seminal 1990 work, New and Improved: The Story of Mass Marketing in America.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

New and Improved offers an expansive survey of how commerce and marketing evolved, tracing their journey from the mid-19th century through the transformative changes leading up to the internet age.

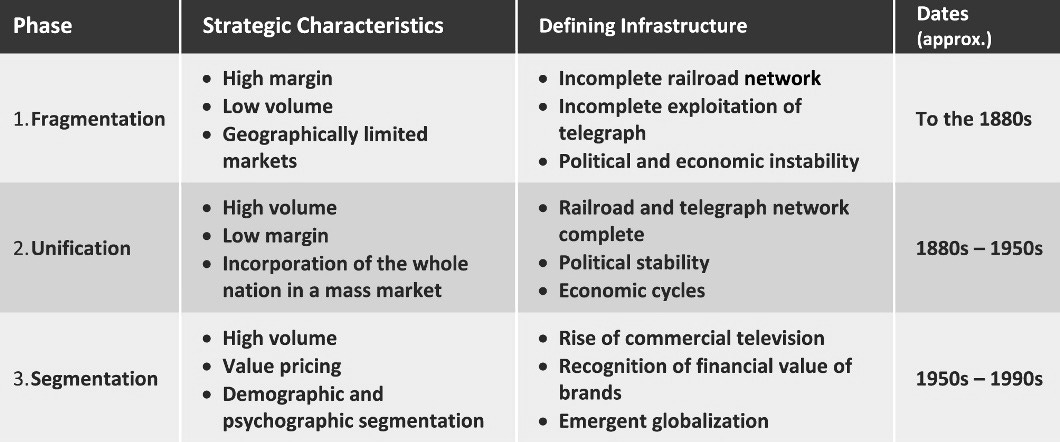

We explore the core concepts from New and Improved, exploring the eras of fragmentation, unification, and segmentation in American marketing. We also discuss how these historical trends continued after the book’s publication with the rise of the internet, mobile technology, and social media.

This conversation is packed with insights, history, and case studies, including:

The profound influence of Alfred D. Chandler Jr. on the study of business history and Professor Tedlow's own work.

The "Cola Wars" between Coke and Pepsi as an example of competitive marketing strategy and the shift from unification to segmentation

The rise and fall of retail giant A&P and the lessons it holds for businesses today.

Professor Tedlow's current work on his Substack, Dystopias and Demagogues, where he applies historical lessons to contemporary societal challenges. (I’m a subscriber and recommend you check it out!)

And much more

Professor Tedlow is a great storyteller, and this discussion offers a rich understanding of how the past continues to inform the present and future of marketing.

Now, here's my conversation with Richard S. Tedlow.

Note - I use an AI tool to transcribe the audio of my conversations to text. I check the output but it’s possible there are mistakes I missed. I have lightly edited parts of this transcript for clarity.

Andrew Mitrak: Richard Tedlow, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Richard Tedlow: Well, thank you very much. It's nice to be here.

Alfred D. Chandler Jr: The Founder of Modern Business History

Andrew Mitrak: I had a lot of fun researching your work, your career, and reading your book New and Improved. I'm going to ask you about all of that. But one person I want to ask you about is someone I heard you mention in an interview. His name was Alfred D. Chandler Jr. Can you tell me, who was Alfred Chandler and what did you learn from him?

Richard Tedlow: Alfred Chandler is basically the man who founded modern business history. I learned a great deal from him. He's most well-known for two critical books. One is called Strategy and Structure, published in 1962. Another is called The Visible Hand, published in 1977.

Strategy and Structure was a study showing the relationship between a strategy that a company wants to investigate or pursue and the structure that the company has, the organizational structure. For example, if you think about chapter two in Strategy and Structure, that's about the DuPont company. Al's middle name was DuPont, and although he was not a member of the family, he was very close to it, Alfred “DuPont” Chandler Jr.

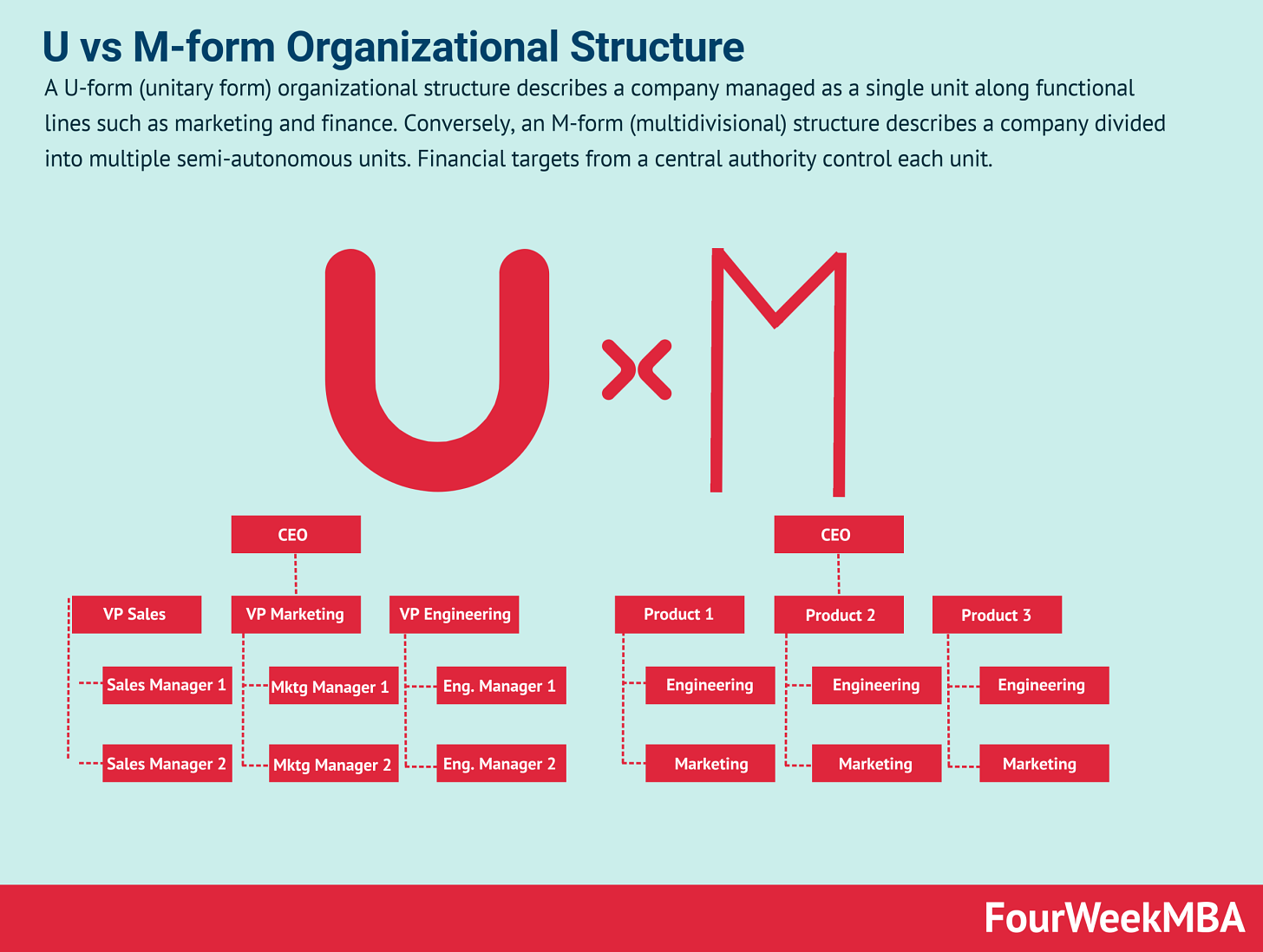

Strategy and Structure is the story of a company, DuPont, which grows very big between 1914 and 1919, decides it wants to pursue a new strategy, which is product diversification, and discovers that the old structure prevents it from doing that. So, Strategy and Structure is the story of a crisis that the company experiences in 1919, 1920, 1921, and how that crisis internally leads it to develop a structure which makes the strategy possible.

The structure that makes the strategy possible is a change from what is called the U-form—the unitary form of a corporation, where you've got a manufacturing department, a marketing department, and that's pretty much it—to a multi-divisional form, called the M-form, which locates the direction of the company around product divisions. So now you have a paint division, which has manufacturing, marketing, and management. That divisionalization became the structure which permitted the strategy of product diversification to take place.

Up until that book, nobody had really intellectualized what it means to try to pursue a strategy with a structure that's holding you back. Nobody made it so clear that structure must serve strategy, not the other way around. That's one thing I learned from Chandler.

When he came to the Harvard Business School in 1970-71, the business history course there was called Business in its Historical Environment, BHE. Basically, it was a nice course, but it was the basic problem with history: it was a bunch of examples, and you didn't know what they exemplified. He changed that course, labeling it "The Coming of Managerial Capitalism." So now the course was about the coming of management to business, and as business grew big, what that meant for the laboring person and the development of unionization, especially during the 1930s, and what it meant for government—the development of government regulation. It was about business, government, and labor.

That was the course I taught for many years. He gave it a fuselage, a raison d'être, which really hadn't existed before. You could take that and build anything off of it. The tree trunk was so hard, so strong, so vital, that all kinds of branches could grow off of it. That was what I did during the 32 years I spent at the Harvard Business School.

The Role of History in Deriving Business Strategy

Andrew Mitrak: It sounds like business history had just been businesses in some historical sense, but was less about how to derive strategies and frameworks from studying business history. Chandler helped make it more relevant, more useful to people by showing how a company through its history changes its strategy and what the lessons are for other companies and contemporary business leaders. Is that part of the right way to think about it?

Richard Tedlow: I think so. That's very well put. History doesn't repeat itself, but it does give you a set of questions. If you attack those questions properly, you're going to come up with the true and righteous way of moving forward. After reading Strategy and Structure (which, by the way, McKinsey & Company, the well-known consulting firm, gave to its managers and partners), you know that the first question you ask when dealing with a company that's got a problem is: is our structure holding back our strategy? What's the relationship between these? The structure should facilitate it, not screw it up.

He gave as vivid an example of that in real life, using manuscript resources, much more so than anybody ever had before. Then, with The Visible Hand, he came up with a master narrative of business history.

The classic problem for an historian (which I've been all my life) is: history is one damn thing after another. The question is, so what? Therefore, what? Chandler gave you the "therefore what," and that was wonderful. It was liberating and very exciting to be around him.

Tedlow’s Career in Business History

Andrew Mitrak: Was Chandler a primary influence that inspired you to become a business historian and spend so much of your career on it, or what were some of the formative influences that led you to pursue this as part of your career?

Richard Tedlow: My father was a business executive. When I was getting my master's in graduate school, I thought it would be interesting to write about a company, which not many people were doing back in 1970-71. He said, "You ought to take a look at Revlon," which was a big cosmetics company in the 1970s. The entrepreneur of Revlon, Charles Revson, was still very much alive. I did. That was what my MA was about. My first refereed journal article publication was in 1976, about Revlon and the quiz show scandals, because Revlon sponsored the 64,000 Question. After that, moving to public relations and how a company presents itself to the public was a more or less natural progression. I decided pretty early on that I wanted to be a business historian.

I first met Al in 1973 at a seminar I was part of and he presided over. Then, when I got to the Harvard Business School, he was already the Straus Professor of Business History, and I got to work with him very closely.

Another lesson, by the way, from working with him: He was working on a gigantic book called Scale and Scope. He gave me a bunch of chapters to read, and I found a mistake in one. I'm thinking to myself, I was very young, not well-known in the profession; he was world-famous. How do I go about explaining to Professor Chandler that this didn't quite work? I told him I thought there was an error. He was very quiet. We met weekly in those days. He said, "I looked into what you found. You're right." He changed his text. Then he gave me a gigantic manuscript and said, "Go over the whole thing. Anything you find, I want to know about." That was really the beginning of our working together. Then we wrote a casebook together, published in 1985, on business history. It was a wonderful relationship for me. I learned an immense amount from that man.

Andrew Mitrak: Studying business history and researching it at that time must have been so different from how it is today. First, business history in general was even more of a niche area than it is now, and also pre-internet or pre-computer-assisted research in the same way. It seems if I were Chandler, I'd be very grateful to have a smart student willing to look over, pour over, and fact-check my work. That must have been a fun time to be working in business history.

Richard Tedlow: It was joyful. We wound up with a very close-knit group of people. At the Harvard Business School—that's an institution—no one goes there to learn history. They don't generate historians. But nevertheless, at one point we were teaching 1300 students business history at HBS. It was our team. There were just terrific people. It was one for all and all for one. It was a wonderful professional experience for me.

Marketing History's Place in Marketing Education

Andrew Mitrak: I'm going to ask you about marketing history within business history because I went to grad school and studied marketing. Most disciplines have some emphasis on history. If I took a geology class, a psychology class, or an economics class—any number of classes—I learned some history of the discipline. But that never really happened with marketing classes. At most, they'd reference Kotler and the 4Ps in the 1960s. It's like there's no marketing history before that.

Why, when it comes to marketing, do you think there's such less emphasis on marketing history? Why is it that other disciplines will probably have the first lesson be some survey of the history of it before getting into modern theories, but that doesn't happen so much with marketing? Why do you think that is?

Richard Tedlow: History has to market itself to marketing. You need as an historian to explain why this is important for you to know. I think the problem lies more with historians than marketers. We have not been sufficiently accessible to the world of marketing. There is a Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM). It does exist. You'll also find marketing articles in the Business History Review, edited at Harvard, which I edited in the 1980s. But you're right. Even if you look at strategy, for example, there's a well-known textbook called The Economics of Strategy. They start with history. I'd like to see more of that in marketing. Maybe it'll happen, who knows.

New and Improved: An Approachable History of Mass Marketing

Andrew Mitrak: When I started this podcast, I was initially looking for a book on marketing history and didn't find one. It was only after starting this podcast and recording a few episodes that I came across New and Improved. It's probably the closest book I found with the expansive history I was looking for. I'm almost grateful I didn't find it at first because I might not have started this podcast had I just found it and read it.

What I love about it is it's written in this approachable style that's not just for academics. Some other marketing history texts or conferences are very academic-focused. This one seems like something I could just pick up and read at the beach, enjoy the story, but also take the lessons. Was that part of your goal when writing this book—to write a more popular book? What were your initial inspirations?

Richard Tedlow: I like to write the way I speak. I like it to be almost as if it's spoken. One of my books is on Audible; I spoke it. Amazon asked me to do that. I want it to be acceptable. Another thing I learned from Chandler is that your research has to be solid because your interpretations may be revised or reinterpreted, but the research, if good, will last forever. If you look at this book and don't think about the propositions or generalizations, but look at the history, you won't find, I don't think, in this compact a form, the history of Coke and Pepsi or of Ford and GM.

My goal is to make it, and in all my writing, I try to write as if I'm speaking. I try to be accessible. Certainly, my teaching was the same way.

Andrew Mitrak: It's primarily focused on America and the 20th century, really the late 1800s up to around 1990 when it was published. Why were you focused on this time and America specifically? Was it that a global history would have been too much to fit into one book, or did you think this was a particularly special time and place to share the narrative of marketing's story?

Richard Tedlow: Both are true. Some of it, frankly, is my own intellectual limitation. I'm an historian of the United States. I was a history major at Yale, got my PhD at Columbia in history, but it was American history. There's a hell of a lot to know just in American history. Those are the archives I've worked in; that's what I know best. So if I'm going to make an academic statement, it has to be based in America. That's where the intellectual capital exists for me. Which isn't to say there isn't plenty to learn from any number of other countries; I just leave that to somebody else who's more global in their perspective.

The Three Phases of American Marketing: Fragmentation, Unification, Segmentation

Andrew Mitrak: So, I'm going to ask more about the book specifically. It categorizes the story of marketing in America into three phases: fragmentation, unification, and segmentation. Can you broadly share with listeners what these are and what these phases mean?

Richard Tedlow: Fragmentation is early marketing. It's before the railroads, before the telegraph. It was a world of high margins, very low volume, and restricted market size because you couldn't get anything anywhere. There were no railroads; it was a canal-based world.

Unification was made possible by the railroad network and the telegraph network. The full force of it really wasn't felt until the 1880s. The railroad network was still in its infancy in the 1850s. In the 1860s, there was a Civil War; you're not going to have national marketing then. In the 1870s, there was a depression. So it was in the 1880s that the great growth of branded merchandise marketed nationally takes place. Coca-Cola was founded in 1886. Procter & Gamble was founded in 1837, but Ivory soap floated in 1879. Kodak was founded in the 1880s. A wide range of other branded products that lasted for a century were founded once it was possible to reach a national market and you also had information through the telegraph.

That's the era of unification. This is an era of high volume, low margin (because you're looking for volume), and incorporation of a whole national market. In the automobile industry, this comes a little later because it took longer from a technological standpoint to have automobiles. But if you look at, for example, the first decade of the 20th century, there were hundreds of automobile companies in 1905, 1910, what have you.

The Model T organized the market. That unified the market and incorporated the whole country in it. After that, the market became segmented. After it was saturated with the Model T (which was basic transportation—it takes you there and it brings you back, was Henry Ford's favorite slogan), Alfred P. Sloan Jr. attacked Ford by coming up with the classic product line, which was divisionalized. DuPont owned a controlling stake in General Motors; they brought the divisionalized structure to General Motors in the 1920s. Sloan came up with "the car for every purse and purpose": Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, and Cadillac. You'd sort of work your way up that ladder, so they'd have a lifetime value of a customer. It was very modern in many ways. That's the world of market segmentation. You see this in lots of different industries. When a new industry is developed, everybody flows into it. Then a couple of leaders sort of organize the market, and then new entrants attack by segmentation. So that's fragmentation, unification, segmentation.

Corporate Combat: Case Studies in Marketing History

Andrew Mitrak: You've alluded to how you illustrate these phases with case studies: the Cola Wars (Coke versus Pepsi), which has come up a lot on this podcast—it's a fascinating way to look at that battle and draw marketing history lessons. Ford versus General Motors, which you just spoke about. Then there's also the story of A&P, once one of America's most popular retailers, though probably not a household name today. And the story of Sears Roebuck. I'll start with the first two: Coke versus Pepsi, and Ford versus GM. There's this corporate combat narrative approach. Why did you settle on that narrative, or what makes it so appealing for drawing lessons from history, seeing these companies duking it out?

Richard Tedlow: Because there's built-in drama, first of all. Secondly, you actually can, by seeing the conflict between the companies, see how marketing progresses. For example, Coke and Pepsi. Coca-Cola was the brand beyond competition. I have quotes in the book; one American soldier in Burma during World War II said, "I think I'm in this damn mess to help keep the custom of drinking Cokes." That's brand loyalty. If you're willing to take a bullet for a brand, that's brand loyalty. Coca-Cola was the brand beyond competition. How do you compete with that?

Pepsi came up with a way. It had been bankrupt in the mid-1920s, but in the 1930s, they came up with "twice as much for a nickel, too, Pepsi-Cola is the drink for you." The idea of twice as much for a nickel during the Depression, when Coca-Cola was selling a 6.5-ounce bottle for a nickel, you could sell a 12-ounce cola for a nickel—that had enormous price appeal. That's how they entered the market; Coca-Cola provided a price umbrella.

Seeing this conflict, to me, made more sense than reading articles in the Harvard Business Review or the Journal of Marketing. I wanted it to be not a history of what academics had said about marketing, but a history of what business people did to market. That conflict provided drama, and also a sense of progress.

The Strategy of Finding an Enemy: Duopolies and Competition

Andrew Mitrak: For marketers and business leaders, is proactively finding an enemy or archnemesis a good part of strategy? It seems like some categories become almost duopolies with iconic two companies. Then there are markets like Coke and Pepsi (though more fragmented now) or Ford vs. GM (also more fragmented now) that were once dominated by two major brands. Is drawing lessons from history about these duopoly dynamics something marketers should proactively think about and strategize around?

Richard Tedlow: When it's a duopoly, in one sense it's good because you're measuring yourself against a competitor you understand. In another sense, it's bad because you need to think out of the box. You need radar spotting the next competitor. Companies that don't do that... Intel was a great company in the 1990s. What the hell happened? By 1999, Intel had basically a monopoly on the microprocessor, a device vital for life in the 21st century, and they lost it. Nvidia, now the headline company, was founded in 1993. How did they miss that, especially with Andy Grove, who always said, "Only the paranoid survive" (a bestseller)? It's important to have competitors, but it's important to focus on the smartest competitors you can find. That's what companies sometimes don't do.

The Cautionary Tale of A&P

Andrew Mitrak: I also want to ask about A&P, a company many listeners might not know, but it was once as well-known as McDonald's. Why focus on them? What's the cautionary tale of A&P?

Richard Tedlow: The first part of the book is from the manufacturer's view. The second, Sears and A&P, is from the retailer's view. Sears marketed everything except food. A&P marketed food—and you need food, clothing, and shelter to make it through the day. A&P stocked America's pantries; it was the power retailer of its time. It also managed a remarkable transition during the 1930s from thousands of small stores to fewer, larger stores because the automobile revolution made it possible to drive to a market rather than go to one on a streetcar and stock up. They managed that transition very well.

The question was, having managed this enormous change so well, what went wrong that made it difficult for them to manage change in the future? That's what that chapter is about. A&P was always looking for the next depression, which led them to sign one-year leases, meaning they couldn't get the best store locations. They were also deeply devoted to private label because they were vertically integrated. When I was a kid, they'd sell Ann Page sugar frosted flakes. Kellogg's was selling Tony the Tiger, which you're probably much too young to remember...

Andrew Mitrak: I remember, “They're great!”

Richard Tedlow: "They're Gr-r-reat!" That's right, exactly.

Imagine you're shopping with a young kid shouting for Tony the Tiger. Are you going to say, "You know what? You can get Ann Page, they're just as good and five cents cheaper"? The kid has a psychotic episode. You don't need to be screamed at much to say, "I'm going to another supermarket and get Tony the Tiger because that's what's coming to me over my TV," which was widely distributed by the 1950s. That was a revolution A&P did not manage well.

A&P in Mad Men: A Metaphor for Decline?

Andrew Mitrak: One way I'd heard of A&P before this book is from the show Mad Men. Have you seen the show Mad Men?

Richard Tedlow: Yes

Spoiler Alert - Please skip this paragraph if you have not watched the show Mad Men and plan to watch it in the future.

Andrew Mitrak: I'm a big fan of the show. It probably like also got me somewhat interested in this historical part of marketing. A&P appears a few times, and it always seems to coincide with a character dying or something bad happening. A grandpa character dies in line at A&P—his generation would have shopped there. A copywriter, down on his luck, starts working at A&P, almost symbolizing his character's death. That’s the last time they refer to him on the show. Then Betty, the main character's wife, is seen shopping at A&P in the last season, and her end is… not good. It's like A&P is used as a metaphor for dying.

Richard Tedlow: It didn't end well.The story doesn’t end well for A&P. The company was incapable of reinventing itself. Its owners, John and George Hartford, were elderly men. They turned the company over to a man who might have revived it, but he died of a heart attack early. Then it was in the hands of Ralph Burger—you'd think perfect for a food store, but it didn't work out. The book quotes an A&P executive: "Cleanliness and courtesy standards, freshness and quality control standards, shelf stocking and checkout standards, and store morale all deteriorated at the same grinding, steady pace." It happened step-by-step. It's the frog in the boiling water story. Before you knew it, you had a boiled frog, and they couldn't compete, while competitors like Safeway and Kroger are still in business.

Andrew Mitrak: It's interesting to see the counter-cycle. A&P with its private labels, then supermarkets with big brands. A&P dies, and then places like Trader Joe's or Whole Foods emerge, almost as a counter-reaction, filling that gap.

Richard Tedlow: Here's a question for you: What did Jeff Bezos do first when he bought Whole Foods?

Andrew Mitrak: I remember seeing Amazon Echos next to the bananas.

Richard Tedlow: The very first thing: he cut prices on a lot of items. If you want to enter a market, price is key. There are two ways to compete: on price or on something else. He came in with price. Whole Foods has its private label, but overwhelmingly, if you go to Stop & Shop or Safeway, they're private label. You can do it that way.

The Fourth Phase: Hyper-Segmentation in the Internet Age

Andrew Mitrak: You published this book at the dawn of the internet age. In later writings, you talked about a fourth phase of hyper-segmentation. Can you share about this or other phases that might have happened after the book's publication?

Richard Tedlow: The internet and social media mean companies now know so much about their customers they can have "markets of one." The dream in the 1990s was to turn marketing into a conversation, not just "buy this, buy this." The amount of data big companies have about buyers and potential buyers is unprecedented. Any book on marketing history now would have to fully grasp what this fourth phase means. That's not easy, but it can be done. There's room for somebody.

Andrew Mitrak: Do you think those four phases have held up since you introduced them?

Richard Tedlow: Historically, they've held up pretty well as a description of what happened in the 1910s, 20s, 30s. It's a good pattern. It's an idea, not just one story after another. The important thing about introducing a pattern is that people can attack it, like Coke and Pepsi did to one another. In the clash of ideas, you grow. Intellectually, life isn't a seesaw. If you come up with an idea and someone else comes up with another, we're both better off. If it stimulates thought... there have been books written incorporating this, not just in marketing. The Economics of Strategy by David Besanko (not my field) uses Coke and Pepsi as an example of attacking an entrenched incumbent. That's not easily answered. But incumbents also have dilemmas: how do you change when you're winning? These are questions the study of history surfaces. This gets back to something I said earlier: history may not give you answers and doesn't repeat itself, but it will give you questions. Then you, with the corner office and big salary, come up with the answers.

The Historian's Challenge: Models vs. Messy Reality

Andrew Mitrak: I'm trying to figure this out through the podcast. I'm collecting interviews, hearing diverse perspectives on marketing history. I was surprised how contentious little parts of history are, how it's not settled, and there's more debate than I expected. Your frameworks (company strategy, transportation, communications, consumer behavior) make perfect sense and fit these phases. But then you see "whataboutism"—what about this edge case that doesn't fit? How do you, as an historian, respond? You can have an elegant model, but it's a model, not the whole world, which is messy.

Richard Tedlow: That's one of the great things about case method teaching at Harvard Business School. You can have a "what about" corner case as a case and ask students, "Is this the future or not?" Let them say. It's the difference between successful people and not. You have to keep a very open mind, but not so open your brains fall out. Within your company, you need principles that guide. For example, "Focus and simplify"—a wonderful instruction guiding Apple. The importance of making decisions that guide the customer.

Steve Jobs believed the customer, especially with a path-breaking product, didn't know what they wanted. It was up to you, not necessarily to ask, but to tell. He always said if Henry Ford had done market research, they'd have said, "Get a faster horse," not "I want a Model T Ford." The market wouldn't have come up with that. Ken Kocienda's book, Creative Selection, about his time as a software engineer at Apple with Steve Jobs, is, though not a marketing book, perhaps the best marketing book I've read. It shows how Jobs made decisions, like the keyboard on the MacBook. It's an education. A classic example of "focus and simplify." Why is that so important? Variety is expensive, complexity is hard to manage. If you focus and simplify, you're ahead. There are principles like that at Apple, but they don't necessarily tell you the next step, but they tell you how to take it. That's wonderful.

Systems vs. Individuals: The Entrepreneurial Spark

Andrew Mitrak: I'm adding Creative Selection to my reading list. This idea of Jobs, Apple, and Ford brings up a tension in your work: systems and frameworks versus individual entrepreneurs who break the mold. How do you reconcile these when telling these stories?

Richard Tedlow: I'm very intrigued. We started with Al Chandler. Strategy and Structure lists companies from the high tide of American business in 1962. Most are dead. What happened? Bureaucratization makes it very, very hard to think about step-function change. Why didn't Sears become Amazon? Sears was the most trusted company, had a national warehouse network, stores everywhere. Why not Sears Web Services? Because Jeff Bezos never would have worked for that bureaucratized company. He had an entrepreneur's soul. Amazon lost money for a long time before becoming a powerhouse. He joked he should have called it amazon.org. But he had an idea, understood how technology would revolutionize retail, and he's smart. That's Amazon. Sears and Kmart don't exist anymore. It's intriguing how difficult it is for an established company to reinvent itself with a step-function change in the environment in which you are doing business. For Bezos, that environment was technology. Sears couldn't reconceptualize its business for the new tools. You needed someone young, hungry, and smart. It's very, very hard for these companies to reinvent themselves.

From Surveys to Biographies: Tedlow's Shifting Focus

Andrew Mitrak: Pulling on this thread of individual case studies: New and Improved is a survey of business history. You wrote another survey of PR, Keeping the Corporate Image. Then your work shifted more towards biographies of specific companies like IBM and Andy Grove at Intel. You also wrote about broader ideas like denial and charismatic business leadership. It seems there's this historical survey of trends, then you get more specific with individuals, and then you take another specific angle on phenomena like denial. Why the shift from surveys to biographies, and what's the role of each for a business historian and educator?

Richard Tedlow: They have to coexist. A lasting biography takes both “the life” and “the times.” You've got to put those together. That's an exciting adventure. The wonderful thing about biography is that, in a certain sense, the biography organizes itself. One thing comes after another as whoever the subject is grows. Somehow it's more, literally, more human. You get a sense of who the individual is making decisions, how this individual pursued his or her career, what decisions they had to make.

Andy Grove, for example, talks about the strategic inflection point. That's the point at which your company either takes off or declines. It is intriguing that you get to these nodes, these places where, if you go right instead of left, there are turning points. You've got to make the right decision at those moments.

Lessons from Apple’s History

It's very interesting, if you look at Apple's history, to see why these people opened stores in the early 2000s. Gateway Computer, which you've heard of...

Andrew Mitrak: I have. I remember visiting a Gateway store out in the boonies, maybe near a Best Buy, but its own place.

Richard Tedlow: Why do you suppose that is?

Andrew Mitrak: I'm sure you have a better answer, but I'd guess it's not enough of a destination for foot traffic. Apple opened stores in malls or iconic places, beautiful buildings that welcome you in high-traffic, often affluent areas. Maybe it's a choice of place. Driving out to a Gateway seems antiquated.

Richard Tedlow: What Apple did was reconceptualize the retail experience. First of all, I think to this day, I don't know how many stores they have, call it 500, maybe more. But when they opened those first stores, it was a place you went to get educated about the product. You're right, you didn't go to the boondocks to shop at Apple. You went to a mall, and it would be right across from Victoria's Secret or a Nike store. Very high traffic. That broke the mold. These are consumer durables, expensive products. Apple has been a premium-priced company selling premium-priced products. Steve Jobs thought it needed explanation and love.

He reconceptualized the retail experience for computers. He did this after Gateway, my recollection is, closed its stores. They tried being their own retailer, closed their stores. He opened his when the company was very small. What a wild thing to do.

Steve Jobs and the iPhone Launch

By the way, the introduction of the iPhone, maybe the most important consumer product of the 21st century, was in 2007. If you look at Steve Jobs's keynote that day, which I think is still online...

Andrew Mitrak: It's on YouTube. I've watched it more times than I can count.

Richard Tedlow: It was about 82 minutes long. There are fascinating things about it. First, he understands it's an internet connectivity device, a phone, an iPod. The iPod arguably is the product that made Apple. There's a beautiful book, The Perfect Thing. The iPod was the perfect thing. Jobs understood if you could incorporate this into a phone, someone else would. Either we do it or someone else does. So he decided to do it: an iPod, a phone, and an internet connectivity device, three in one. But if you look at that keynote, he mentions the camera in like one minute: "By the way, it has a 2-megapixel rear-facing camera." I don't know if this is true, but my guess is that camera is one of the top five apps on the phone. How many photographs are uploaded to the cloud every day? Steve Jobs himself, and also the App Store, he didn't fully appreciate what he had there. But somehow it was open enough so it could grow into this unbelievable product.

Andrew Mitrak: My guess is also the level of focus. Storytelling is an editing process; it's what you leave out. As a great pitchman, he knew if you included all ideas—four things in one, or it's also a calculator—it's too much for the brain. Three is an elegant, magic number. Even if he included the camera (probably my favorite app on the phone, I use it a lot), I wouldn't remember it the same way if it was four in one versus three.

Richard Tedlow: I think there's truth to that. That keynote was a remarkable display of what he had and the team he had. People yelling and screaming in the audience, all Apple engineers. It was a joyous moment, and it gave you a sense of how exciting it is to play on a winning team in business. He was able to construct that. That's part of the company's strength that Tim Cook, one of the great business executives in American history, took that ball and ran with it. Boy, did he. It's fantastic.

Teaching at Harvard vs. Apple University

Andrew Mitrak: We're talking about Apple. You were a teacher at Apple University and spent a big chunk of your career as a professor of business history at Harvard. How do those two experiences compare? Did people immediately understand the benefits of learning business history, or did you have to paint the picture of why it matters today?

Richard Tedlow: There was no need to sell it at Apple. One of the biggest differences is that at Apple, you didn't have to grade papers. I'd have 200 students a year; that was three weeks of grading for the final, and early in my career, midterms too. That was hard. Also, at Harvard Business School, there was a forced curve. Very smart students, but 10-15% you had to give the lowest grade to. That was hard. You didn't have to deal with that at Apple.

You didn't have to sell history because at Apple, you weren't so much teaching history as teaching decision points. Since you knew how things turned out, you could dissect something and say, "Okay, I can tell you this decision resulted badly. I want you to tell me why." So here's the story. You tell me what went wrong and where. You learn that at Harvard Business School. One of the first cases I taught in marketing was a salesman's diary. It was, you know, on September 12th this happened, on October 5th this happened. I'll never forget this case. The guy lost a sale. All you had to do was say to the students, "All right, here are dates. The guy kept a diary. Where did he lose the sale?" That happened. It's the past. But this is a dilemma any salesperson faces. What went wrong and where? Cases like that you could teach anywhere; it's a pleasure.

Dystopias and Demagogues: History as a Warning

Andrew Mitrak: I also want to ask about Substack and Dystopias and Demagogues. It's a Substack I read, and the stakes feel higher compared to your other work. I read it, I recommend it. I wouldn't say I enjoy it, but "enjoy" might not be the right word because it gives me anxiety. I think that's partly the point: using historical examples to ring alarm bells. Can you tell me about Dystopias and Demagogues and your process?

Richard Tedlow: I'd be delighted to. I started writing this in August to explain to myself what was going on in the United States. I publish on Tuesdays at noon Eastern Time. I don't try to write daily like some, but that's not me. I want to use what's going on today as a hook, but I'm an historian, so I want to go back and say, "What can we learn from the past?" For example, this country, and I never would have said this 15 years ago, seems to be turning its back on democracy. That's very dangerous.

History can tell you what has happened to countries that made that choice, what the symptoms are, and perhaps suggest solutions. I'm 77 now, so the clock is ticking for me. When I look at the country, I'm more concerned about its future than ever. Being an historian, I think the country is in more trouble now than ever, including the Great Secession Winter of 1860-61. We're getting warnings that many people are discontent. As a result, we have the president we have now. It's unclear to me if he's a cause or a symptom. That's something I try to work out.

I also believe Dystopias and Demagogues has encouraged me to realize even more vividly the importance of history. George Orwell said, "He who controls the present controls the past. He who controls the past controls the future." I believe that's true. History has never been as important as now. It's distressing that so many universities are losing focus on history due to expense and the need for practical knowledge, which I understand. Nevertheless, studying history helps tease out fact from fiction. A classic example: what happened in Germany from 1919 to 1933, the Weimar Republic. Life was difficult for statesmen there because of the "stab in the back" belief: that Germany hadn't lost WWI but was betrayed by leftists, Social Democrats, communists, and Jews. The result of that myth was, in part, Adolf Hitler becoming Chancellor in 1933, leading to 12 years of hell.

A lot of that was because of a mistaken belief in history. Germany lost WWI on the battlefield. There were revolts, a revolution, the Kaiser was kicked out. Germany's allies had given up. The war was going to end. But because of misunderstanding what happened, horrible things took place. An acute, honest understanding of the past is very important in moving forward. That's what Dystopias and Demagogues is about.

I agree, it's not like New and Improved, which has laughs. The Cola Wars are fun. The current situation isn't as enjoyable. But it's important to face facts. That's what I try to do. It's also a way to keep in touch with thousands of former students. I love hearing from them, taking their advice, learning from lead users—very important. Anyway, that's the story.

Andrew Mitrak: The current situation can evoke many feelings, and sometimes people don't know what to do. I'm glad you've found this productive outlet, writing these thoughtful historical essays. It's an example of doing something productive instead of just venting. I publish this podcast on Substack weekly too, and having a weekly practice is something I've personally enjoyed.

Richard Tedlow: It organizes your life positively.

Andrew Mitrak: Aside from subscribing to Dystopias and Demagogues, where else can listeners find your work?

Richard Tedlow: I don't think so. I have books through Amazon. Giants of Enterprise I enjoyed writing very much. It was a number of years ago. But it's fun to re-engage with business executives like Sam Walton or women like Oprah Winfrey or Mary Kay Ash. These are remarkable, often "think different" stories. It was fun to research and write about them. That's online if anyone's interested—Apple Books or Kindle.

Andrew Mitrak: Great. Richard Tedlow, thanks so much for your time. I've really enjoyed this conversation and appreciate your work. I look forward to reading more of your books.

Richard Tedlow: Thank you very much. It's been a pleasure to chat with you.