A History of Marketing / Episode 26

Today marks the first day of San Diego Comic-Con 2025, which feels like a fitting time to explore the incredible intersection of comics and marketing.

Comics were once a niche, nerdy subculture but for the past two decades they’ve grown to dominate the global box office and are at the center of pop culture. So how did comics market themselves to the masses?

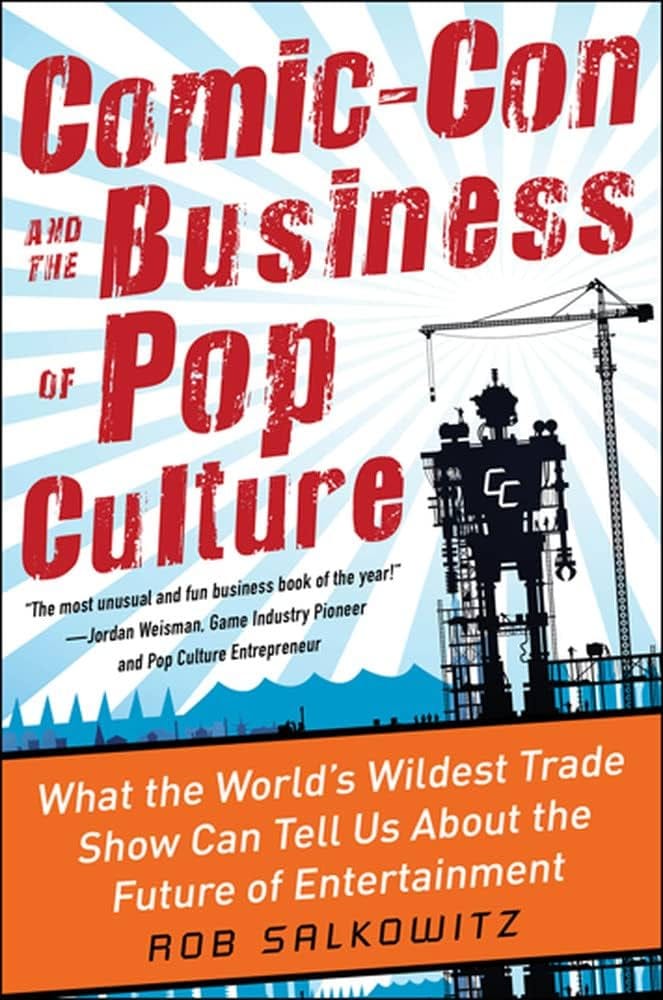

To help us understand this journey, we have the perfect guide: Rob Salkowitz. Rob writes for Forbes and is the author of the book, Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture. He's also a professor at the University of Washington, where I was lucky enough to take his class 12 years ago.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Rob takes us on a tour that reveals the intertwined history of comics and marketing, a connection that runs deeper and further back than you might imagine, rooted in the very DNA of mass media.

Here’s a glimpse of what cover:

The relationship between early comic strips and print advertising

How comics evolved from selling newspapers to serving as WWII propaganda

Stan Lee’s brand-building genius and how Marvel marketed itself baby boomers

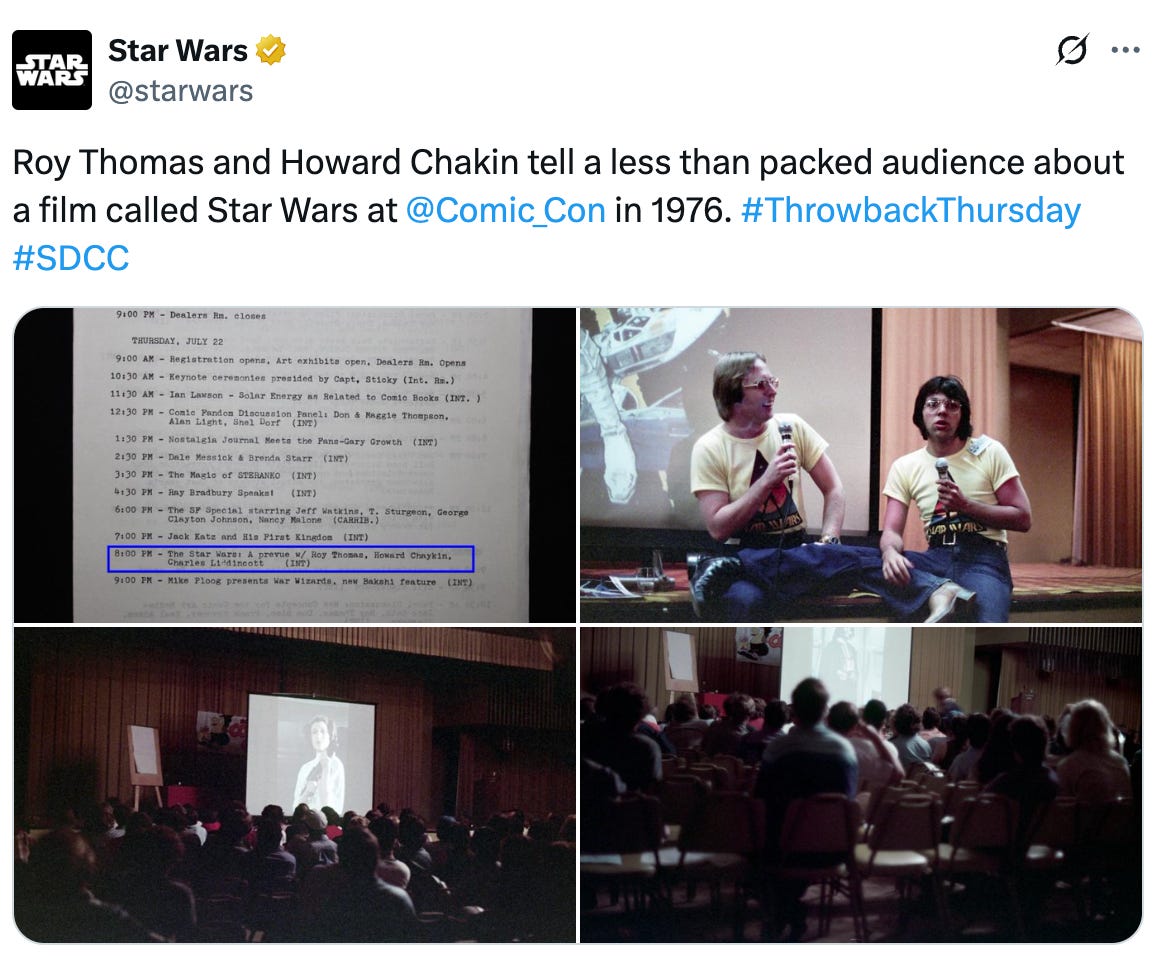

How George Lucas launched Star Wars at Comic-Con in 1976, creating a blue-print for Hollywood blockbuster launches at SDCC

Timeless marketing lessons on activating superfans, creating scarcity, and how in-person events can create meaningful marketing moments

Now here’s my conversation with Rob Salkowitz.

Note - I use AI to transcribe the audio of my conversations. I review the output but it’s possible there are errors I missed. Parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity.

Comic-Con: From Niche Gathering to Global Launchpad

Andrew Mitrak: Rob Salkowitz, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Rob Salkowitz: Happy to be here.

Andrew Mitrak: Before we go back into the history of comics and marketing, I want to start with where we are today. I'll be publishing this on day one of San Diego Comic-Con, which is the biggest event of its kind in the world, and you are one of the world's leading experts on Comic-Con.

This event started more than 50 years ago as a gathering of geeks, and now it's where the world's largest media franchises launch new movies and TV shows and video games. Can you just paint a picture for us—for somebody who's never attended or hasn't been to a Comic-Con before—what is the modern San Diego Comic-Con? What does it look like and sound like and feel like to be on the ground floor of one of the world's biggest pop culture trade shows?

Rob Salkowitz: Sure. We're talking about 150-200,000 people that are able to get to the convention itself, and probably another 200,000 people that are in the streets of San Diego just there for the vibe for the week. It's one of these big events that combines a lot of different stuff. So there's entertainment, there is technology, there are comics and games and all of the things that go into that.

It's a combination of a lot of different fandoms. It's a big opportunity for studios to showcase their upcoming stuff to the adoring public. And as we got into the social media age, it's become a premier place for influencers and everybody with a selfie stick and a platform to get up because the backgrounds are great. It's incredibly lively, it's visually appealing. There's a little bit of Mardi Gras, there's a little bit of the Super Bowl, there's a little bit of the Oscars. I mean, it's glamour and weirdness and exuberance all packaged into one thing.

Andrew Mitrak: Do you think that's a reflection of comics themselves as a cultural touching point, permeating through other things? Or do you think it's partly just the convention itself expanding to encompass more, or just a little bit of both? How would you think about that?

Rob Salkowitz: If we roll the tape back a little bit, Comic-Con began, as you say, in the early 1970s, and the people who were fans and collectors of comics were very much a subculture. Especially adults who took comics seriously enough to study them, to collect them, to want to get together and talk about them in large numbers, to meet the creators of them—that was a minority even when comics were still kind of mainstream. And then as you get into the 70s and 80s and comics vanish from the newsstands and are sold almost exclusively through comic stores, you really had to be the kind of person that was really into it to seek them out, to find them.

But at the same time, that audience became much more devoted because they were being fed a product that was being optimized just for them. So, comics through this period of being at the margins really got compressed into this very potent, well-connected subculture. And among the people that were part of the subculture were a lot of creative-minded people. So even starting in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the people that were reading the comics, they came in, became writers, became television people, became people like George Lucas who were highly inspired by the stuff that they read in comics and went out and started making movies.

And in fact, the first place that Star Wars appeared before the public was at Comic-Con in 1976 when they brought it around as a roadshow to say, "Take a look at this thing that we're cooking up."

The Power of the Superfan

Rob Salkowitz: The advantage of this as Comic-Con developed is that if you're doing a project, a commercial project, whether it's an entertainment book, a game, or anything, you want that critical mass of fans engaged first. So if you can get those people activated to come to your opening day weekend, to buy your game or your book on the first week in enough numbers that it puts it up into the bestseller list, that it puts it up at the top of the charts, there's a lot of people that will go and then go after something just because it's popular.

You really need to activate those fans. Once we started seeing social media platforms coming around at the end of the ‘00s, the value of having all of these hardcore fans that were very vocal, that were very credible, and all of these people out there on their channels saying, "I was just at Comic-Con and I saw the preview to the coolest movie, and we all need to go and see that"—the marketing power of that and the brand-building power of that was way in excess of anything that these brands could buy through ordinary channels.

So, it was around that time—I wrote my book in 2012, and I was observing how all of these things were kind of converging together—and the power of this for marketers in the first place was, you want to get that core audience of superfans activated and engaged. You want to pull out all the stops and have your Hall H presentation, unveil all the stars and the exclusive clips, and have everybody holding their cell phones up and, you know, having the signs that say, "Absolutely no video recording," knowing that within five seconds, the entire world is going to see all of this stuff. That's the dynamic that was at work as Comic-Con grew from being a niche activity into being the gigantic extravaganza that it is.

The Shared DNA of Comics and Advertising

Andrew Mitrak: You gave a preview of how Comic-Con grew to become the extravaganza it is. I want to dive into that deeper, but before we do, I thought I'd take a step back into history and sort of look at how marketing and advertising and promotion and comics more broadly have been intertwined over the years. Then we'll get to how that planted the seeds for something like Comic-Con.

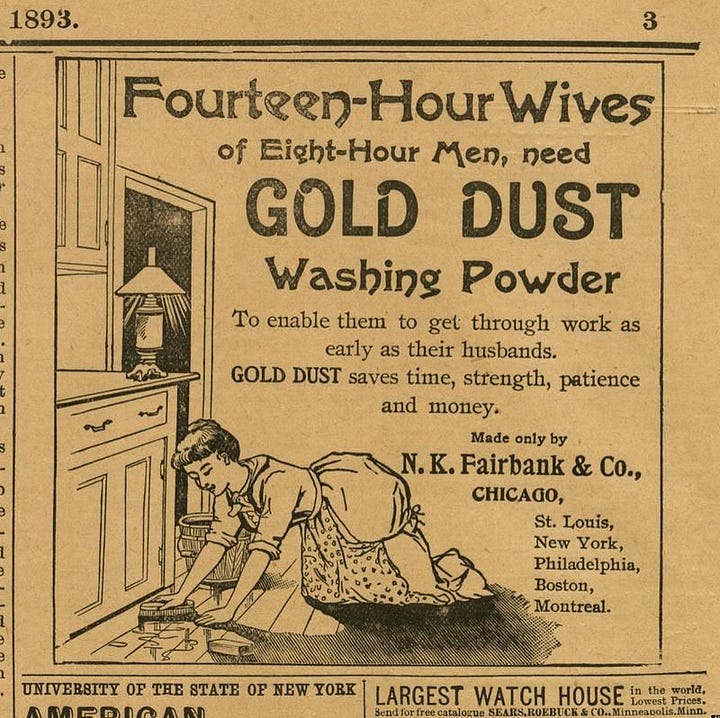

When I look at the origins of advertising, I think it has a lot of similar DNA to early comics. If you look at early newspaper comic strips and early print ads, they both use visual storytelling and memorable characters. There's this idea of marrying art and copy together to help convey a lot of information to somebody.

But also, the art part of it, the comics part of it, being accessible to a large number of folks who aren't necessarily reading every word. And also, of course, using humor, of course, in a comic strip or often in advertisements.

You're an expert in both marketing and comics. How deep do you think this connection is, or am I grasping at straws trying to make this connection?

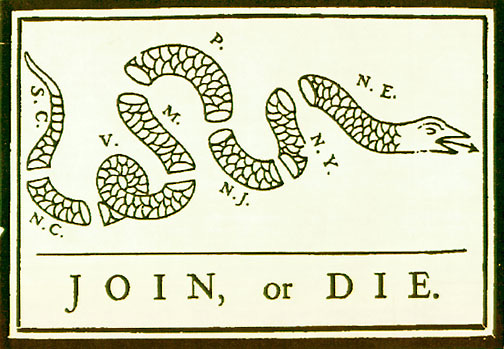

Rob Salkowitz: They both come from the same source, which is that on one hand, human beings love stories. We are attracted to storytelling media in general. And the combination of words and pictures, or sometimes just pictures and visual storytelling—there's a whole prehistory of comics that says, "Oh, cave paintings and tapestries and all of these things." And it's true. When you see stories represented in this way, where it's a sequence of images or something that our mind can picture visually, it activates your brain in different and more primal and instinctual ways than going through a medium like text, for example.

As soon as newspapers were able, as soon as printing technology was good enough to be able to reproduce decent-looking artwork, you started seeing, first of all, editorial illustrations, you started seeing illustrations that would accompany stories. Before you could reproduce photos very well, it was drawings and it was artwork. And one of the things that newspaper editors realized is sometimes simpler images work better than highly detailed, realistic images. So having that simplified visual medium at your disposal was really important.

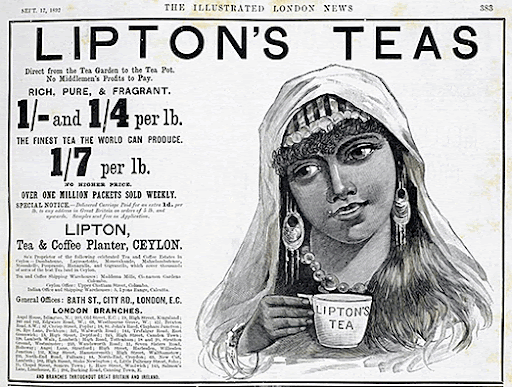

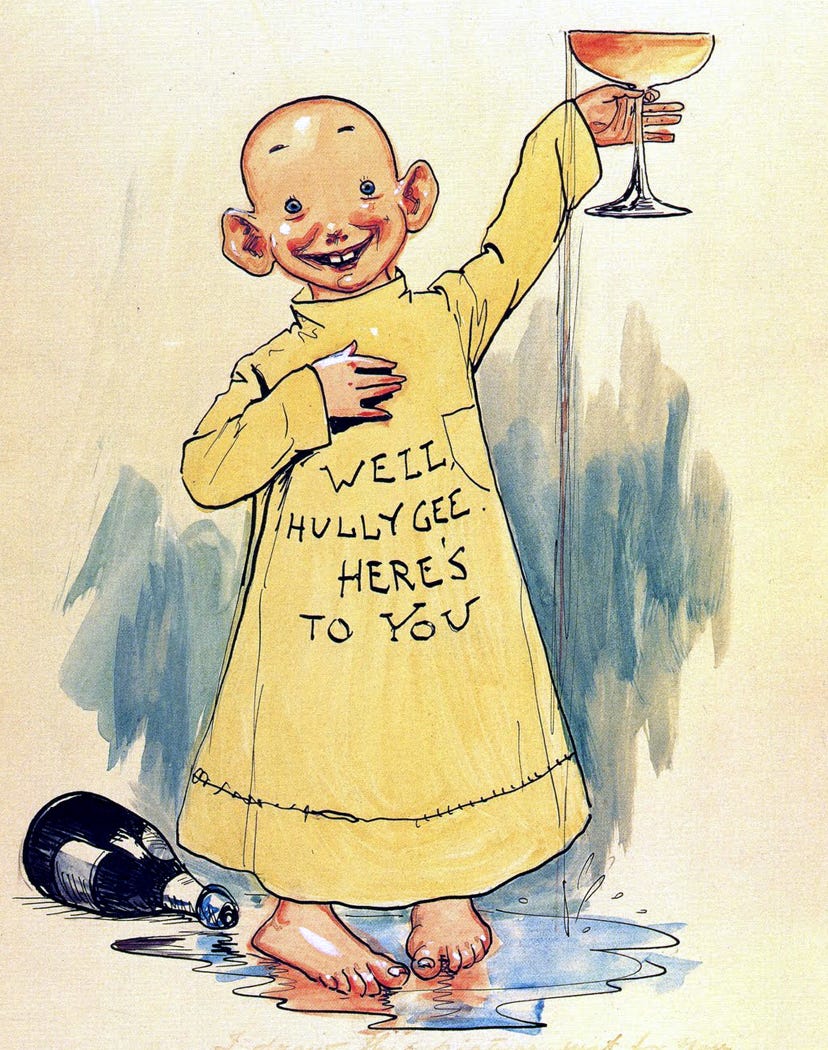

If you look at when comics started appearing in newspapers around the turn of the 20th century, it was the comic strips that sold the newspapers. There was a very popular early comic strip called The Yellow Kid that appeared in New York newspapers, and one of the publishers—Hearst and Pulitzer were the two publishers of the competing newspapers—and I forget who stole from whom on this one, but somebody stole The Yellow Kid from the other one as a way to sell newspapers. And that's where we get the term "yellow journalism," meaning unscrupulous, shady journalism. The fight wasn't over the stories, it wasn't over the facts; it was over the comics.

Andrew Mitrak: And in some ways, comics sell the newspapers, and advertisements help fund and subsidize the newspapers, so they're all kind of working together.

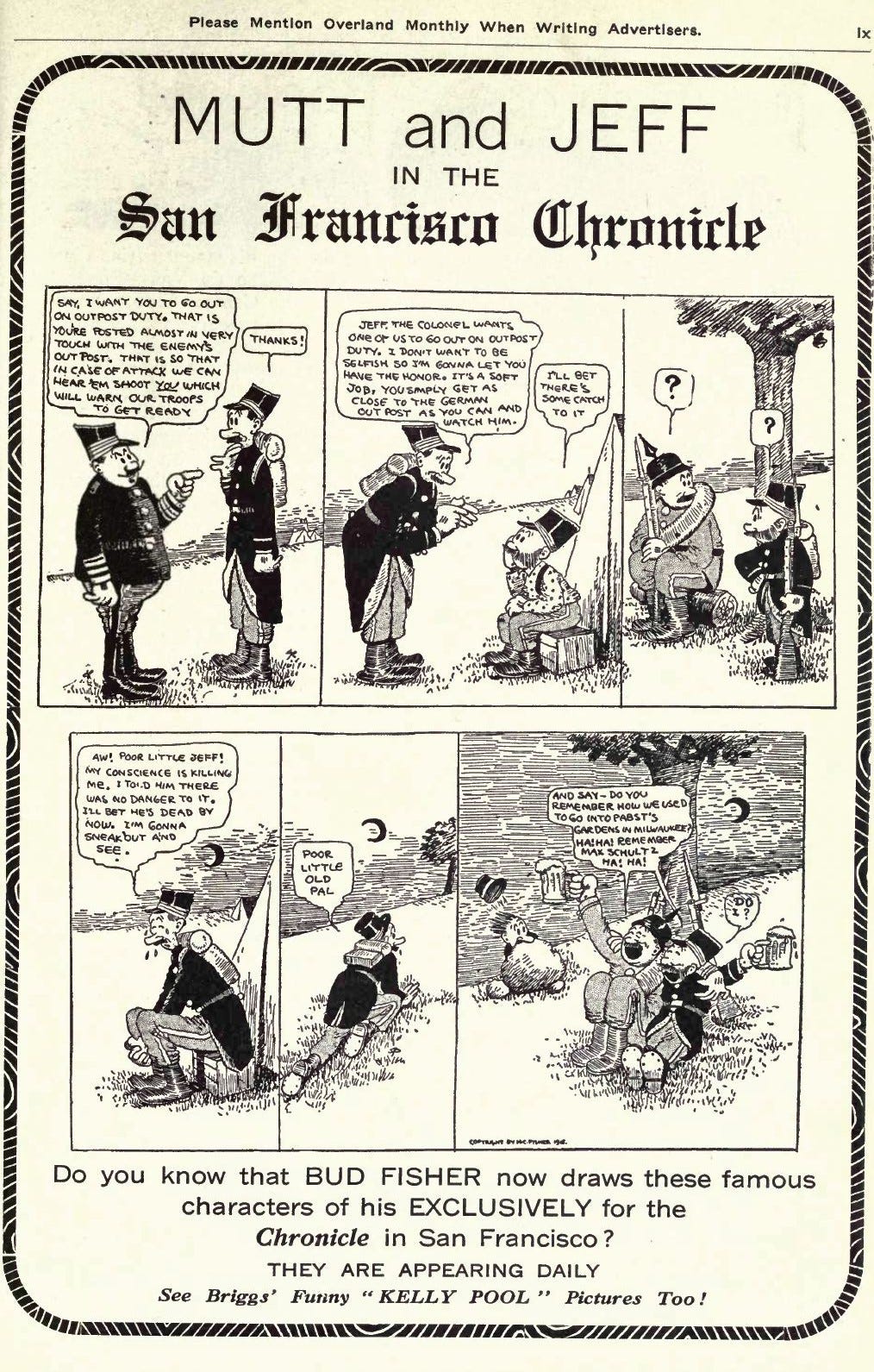

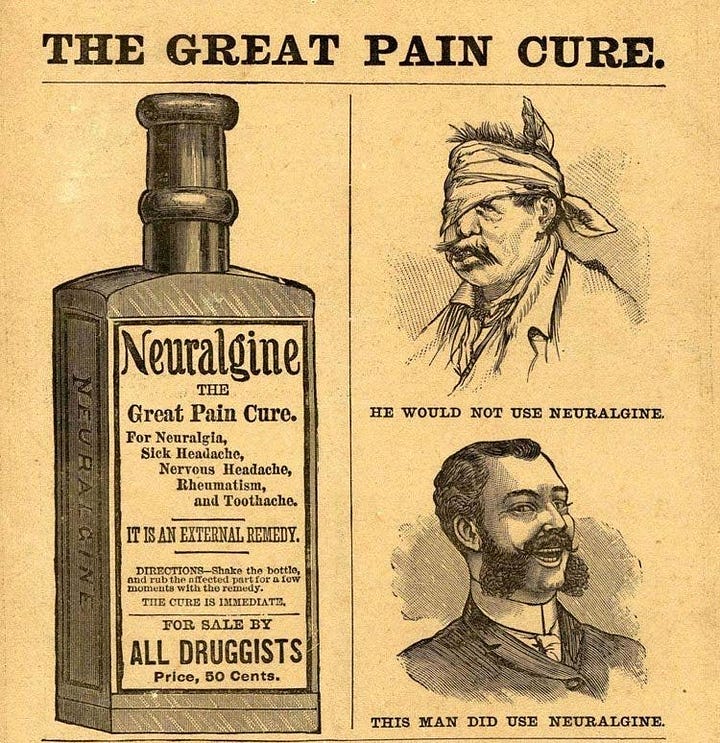

Rob Salkowitz: Exactly. And the advertisers also saw that comics were a potent medium. And then also, the comics were such a popular thing around the 1910s and 20s. The people that were doing the early comic strips—Mutt and Jeff, and Gasoline Alley, some of these really old original comic strips—were celebrities. They were in every newspaper, and they themselves were endorsing products. There's some very funny advertising of, "Bud Fisher, the guy who does Mutt and Jeff, uses this kind of razor," as if the endorsement of a cartoonist was somehow important or influential, but maybe it was.

So, those things grew up together. The comics and advertising as mass media grew up together. There were a couple of ad agencies in the 40s and 50s that specialized in doing comic-style ads, and some of the really good comic artists of the 60s and 70s actually came through that studio and learned how to do this sort of realistic illustration style preliminary to that. So there's a lot of crossover in the media itself. That's an untold story, I think, that's not widely known.

Andrew Mitrak: I think that The Yellow Kid was actually used to endorse products or would be put in things. So the comic character is selling the newspaper, but it's also not limited to that strip. The character would wind up promoting adjacent products somehow, just as a way to advertise to kids or advertise to folks who are familiar with the comic.

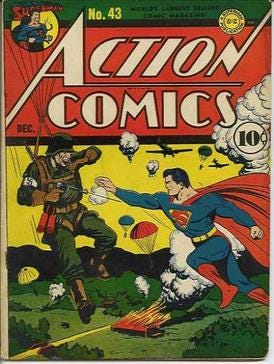

Rob Salkowitz: And you had these pop culture characters that came out of that period, like Tarzan, who didn't originate in the comics; he was a prose character. But as soon as original characters started coming out of the comics, within six months of Superman in the comics being a bestseller, there was a Superman radio show, there was a Superman book, there was a Superman animated movie serial, and product tie-ins and all of these things because advertisers always want to get on board with what the public likes. So the connection between comic characters and commercial communication was established at the earliest possible opportunity.

Understanding Comics and Communication

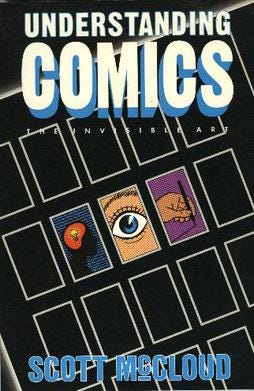

Andrew Mitrak: A lot of what you were speaking to earlier as well with comics as a sequential art medium to convey information, it reminds me of a book that you introduced me to when I took your course, Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, which is one of those books that you think it's about comics when you read the cover, then you realize, "Oh no, it's just actually about communication in general and how humans interpret information." And like you were saying, how a simpler character that's abstracted is actually easier for us to digest than a hyper-realistic image. And I just think that's one of the great books that you turned me on to, just as I think there's a lot of marketing communication lessons in that book as well.

Rob Salkowitz: When I teach it in my class, a lot of the students that come through my class aren't interested in comics per se, but a lot of them are UX designers. And there is no better UX that's ever been invented than comics. For all of the reasons—McCloud is very technical in the way that he breaks down this experience of reading a comic panel to panel as a series of still images engages your mind in a particular way that's different from watching video or different from reading a book or something like that. And the ways that the characters are represented on the page and the artistic choices made by the artist and the visual storytellers involved with it are all very deliberate, and they're meant to guide your eye around the page or to make an emotional impression on you.

So it looks very simple, and you look at something like Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes or something like that, and it's so simple, but under the hood is a 12-cylinder engine. I mean, there's a lot of very powerful storytelling levers that are being and dials that are being manipulated and turned to make it look easy. And that's the unique power of it.

From Comic Strips to Comic Books

Andrew Mitrak: Mostly we've been talking about comic strips so far—Peanuts and The Yellow Kid and that—but at some point, they emerge into books. And when did that happen? When did comics sort of go from the strip to the full book?

Rob Salkowitz: In the United States, it was in the early 1930s that a couple of entrepreneurs got the idea to package together a bunch of Sunday newspaper comics into a folded-over book that was distributed on newsstands. Within a couple of years, they were exhausting the ready-made material that had already been printed, so they started doing original stuff.

The other thing sociologically that was going on is that there was a huge influx of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe at that time. And the kids and the zero and first-generation people that were coming to this country were often denied opportunities to get into commercial illustration, advertising, comic strips as opposed to comic books. A lot of the doors to the more lucrative avenues for those kind of people were closed. And so, with the entrepreneurship that we associate with a lot of immigrant communities, they were looking around and saying, "All right, let's do this as comic books." So you had a lot of very scrappy and, in some cases, not terribly scrupulous entrepreneurs, a bunch of hungry, young, idealistic artists, kids that had no particular place to put their stuff. So that, those things all came together, and we saw original ideas. If you unpack what Superman is about, it's kind of an immigrant fable about a guy who comes from somewhere else and he's trying to fit in and he's trying to do the right thing with the rules of his culture and all of this sort of thing. And it's kind of a power fantasy of people that are not allowed to rise naturally in the society that they're in. And those are very potent stories, and it captured the imagination of a lot of people.

From Comic Books to Propaganda Tools

Andrew Mitrak: You mentioned how Superman had a subtle telling of an immigrant's tale. But then as World War II breaks out, it becomes a lot less subtle, and comics become more of like propaganda to support the war effort. And folks like Superman and Captain America, they're icons of America and icons of good. How would you characterize the use of comics as a tool to support the US war effort in World War II?

Rob Salkowitz: From a marketing perspective, the kinds of messages that you need to get people riled up about wars are not terribly subtle, and they depend a lot on stereotype and simplification and things like that. And again, you have a medium like comics that is tailor-made for that. It went hand-in-hand with radio, which was another mass medium that was happening at the time, where you got this one-dimensional view of what was going on. There was the person that was talking and there was not anything else to distract you from that.

So those two things together, and the fact that a lot of comic characters were on the radio at the time and things like that. So, it was very effective. And in some of the later, immediately after World War II, there was a big critique of comics, attempts to censor comics and drive them off the newsstands. And interestingly, the main critic of that was coming from the left, not from the right.

And his perspective was that comics were a tool of indoctrination and propaganda and that it was the crude simplification of these images that was making people into docile cannon fodder for the imperialist war efforts and things like that. Not that he was pro-Nazi—I mean, he was a German refugee—but his view of the world was that the lower down the discourse was, the worse off humanity was for it. And so he was pointing at comics as making all of our minds cruder because of that. He didn't appreciate or get all the other stuff that was going on. What he saw is, during World War II, there was a lot of racist and jingoistic and very crude stuff going on as a part and parcel of the war effort.

Early Comic Book Ads

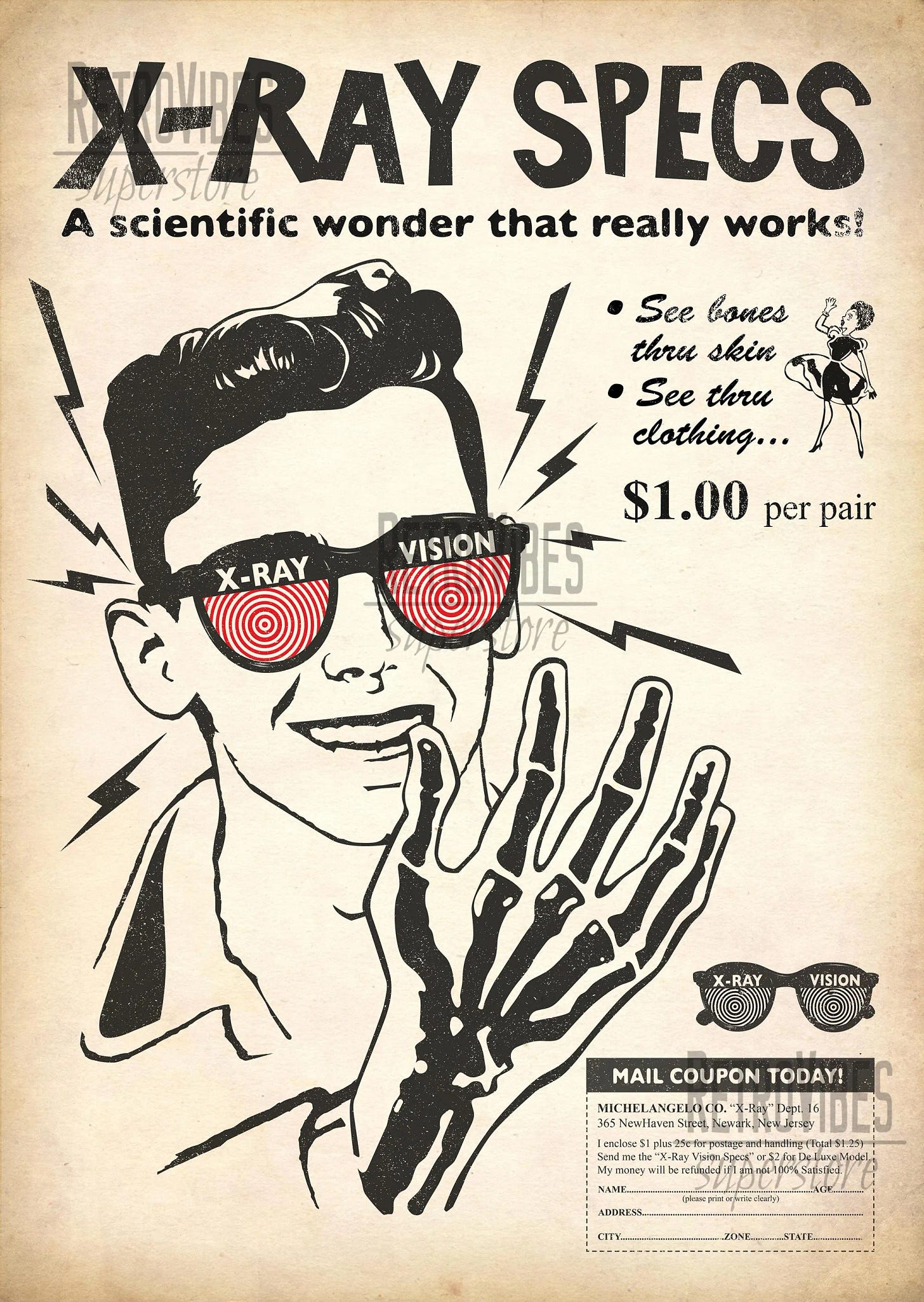

Andrew Mitrak: So, on this thread of indoctrinating children, it's funny also to me is when I look at the ads inside of comics at this era, it feels like a lot of what you think of like the X-ray specs and the sea monkeys and whoopee cushions. Were those the kind of ads that were inside of comic books at the time? Or was that sort of what funded them, or how did that work?

Rob Salkowitz: You have to realize, from today's perspective, when we look at the Fantastic Four movie is going to make a billion dollars and all this stuff, comics were a very low-born business. The kind of people that were involved in the production of comics were not terribly far removed from gangsters, and some of them actually were gangsters. The newspaper distribution of comics was tightly controlled by organized crime and some very corrupt stuff going on. And so a lot of the ads were packaged by these advertising companies that specialized in very low-rent kinds of stuff. And they would divide the page up into sixteenths or something like that. So you would get all of these weird, tiny little ads to separate kids from their dimes for plastic toy soldiers or X-ray specs or hovercraft, whatever.

The Rise of the Comic Book Mascot

Andrew Mitrak: It's funny though, also, it's around this time that you can see marketers in major companies taking inspiration from comics. Like the Kool-Aid Man emerges in the 1950s, and Bazooka Joe, and Tony the Tiger. Mostly things that are creating mascots. While they weren't comic book characters themselves, they look like they could be comic book characters, and they have a lot of the markings of a comic book character. It seems like they've drawn some inspiration from comics. I mean, Bazooka Joe quite literally using the comic as a way to sell the gum. Is that something that you've come across in your research at all, of marketers in this era being inspired by comic books?

Rob Salkowitz: I haven't made a careful study of it, but you could see a couple of things. One is, comics were very popular with kids. If you had a product that you were selling to kids, then it's like, "Oh, it's comics, like Captain Crunch or something like that, he looks like a comic character." There was a lot of overlap between the audiences and the language that you were using to speak to the audiences. There was also the ad illustration and art industry was starting to open up. So a lot of the, frankly, many of the people that were driven out of comics by the censorship and the witch hunts and panics of the early 50s ended up in advertising, where they were doing illustrations, they were doing storyboards, they were doing character designs and things like that. And again, there were people that were working in advertising who would eventually end up in comics. There are not that many job opportunities for commercial artists and illustrators out there, so there's going to be a lot of overlap, I think.

The Marvel Age and the Rise of Youth Culture

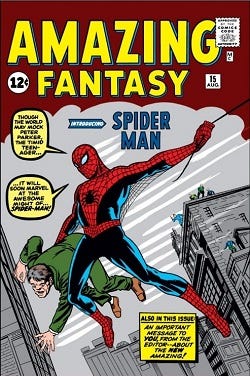

Andrew Mitrak: In the 1960s—in '61, the Marvel era of comics begins. You start to see comics for the first time represent youth culture. Spider-Man is a character that's a young person; I think a high school student. Before that, while comics were popular among kids, they usually featured Superman or Batman or guys who were older adults as characters. How did Marvel market themselves compared to what came before them? How did Marvel stand out or counter-position them as a new type of comic brand?

Rob Salkowitz: Some of this is demographic, right? So you have the Baby Boom starting in 1946. So these boomers, the oldest ones are 11 or 12 in the late 50s, and they're reading these kind of not terribly challenging Superman and Archie and stuff like that. And they get to be about 13 or 14 in that era, and they're looking around for something that's maybe a little more satisfying intellectually. And so they'll glom on to anything that's not as insulting to the intelligence as some of the stuff that was being done elsewhere in that time. And Stan Lee was a very shrewd and ambitious guy.

The extent to which he was responsible for the creation of these characters is very much in dispute right now. But one thing that Stan Lee was is a master marketer. This guy really understood not only that the content is going to sell, but that the brand sells. And so what Stan Lee brought to Marvel Comics—more than Spider-Man, more than Silver Surfer and Fantastic Four and the Avengers and all of this stuff—was this feeling that if you were reading a Marvel comic, you were part of something that was cool and fun and buzzy and bigger than the one issue that you were reading.

Because Stan Lee invented this concept of continuity, where you would pick up an issue of Spider-Man and Doctor Strange would be a guest character in the Spider-Man, and he would refer to something that was happening in Doctor Strange comics, or Daredevil would be fighting with a character from the Fantastic Four. And if you were reading any of these comics, you felt like if you weren't reading all of them, maybe you were missing something important. So he would promote the comics with his internal ad pages, and he would communicate with the readers in a voice that was very authentic. And he did this in a conscious way.

He wanted to differentiate himself from DC, which was very official and standoffish and stuff like that. And he wanted to be the big brother, the best friend voice. He wanted to make the readers feel like they were part of something.

And yes, it helped that he had geniuses like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and people like that that were doing the stories, that were creating the characters, whatever his role in that was. But all of those guys worked at other companies over the years, and none of their stuff made people care, made people open their wallets and open their hearts as much as the stuff that they did with Marvel. And a lot of that was due to the brand-building genius of Stan Lee.

Andrew Mitrak: He also wrote letters or he had readers write letters in, and then he responded, and he had his catchphrase, "Excelsior!" and all that stuff. And really humanized and built true fandom to have the creator and the mastermind behind this Marvel Comics universe write you a letter and respond to you and have a human connection. It feels way ahead of its time.

Rob Salkowitz: Way ahead of its time. It's like you could build a brand-building textbook from studying how Stan Lee built the Marvel brand.

We say the Marvel Age of Comics started in 1961. Well, yes, that's when the comics started coming out, but it was 1964-65 when people started caring about them and honestly, when the quality became consistent enough that it was worth caring about, because it took a while for that to sink in.

And what he also managed to do was, instead of the readers that would read—they were 9, 10, 11 years old, be reading the comics, become 12, 13, get interested in other stuff, throw the comics away—those folks would stick with it because they wanted to find out what happened next. They didn't want to leave this community behind. So they get into high school, they get into college, they have more stuff on their minds, and they start writing letters that reflect, "Why aren't you talking about the civil rights? Why aren't you talking about Vietnam War?" These are the things that are important to us. And that encouraged Stan and some of the younger creators that were coming into the business, many of whom were fans themselves, to say, "There might be an opportunity to make these stories a little more complicated, make them a little more sophisticated."

Then it starts to be these comics aren't just good to be adapted into Saturday morning cartoons; maybe some of these stories have longer legs, maybe some of them have more commercial potential. And that's when you have a company like Warner Brothers taking an interest in DC and stuff like that. So larger entertainment companies start saying, "Hmm, there's something to be had."

The Origins and Evolution of Comic Conventions

Andrew Mitrak: So in the last 10-15 minutes we’ve covered an expansive history of comics, though I think it was pretty good for a concise interview. Coming back to Comic-Con, when did comic conventions in general start?

Rob Salkowitz: Yeah, I mean, they come out of an earlier tradition of science fiction conventions. The science fiction fan community was pretty well established, and a bunch of the early comic creators were originally sci-fi fans in the 30s and 40s. Some of the sci-fi writers, like Ted Sturgeon and stuff like that, wrote for comics. So there was a lot of overlap, and the sci-fi community already had a fan culture that we would recognize as such.

So in the late 50s, early 60s, some comics stuff started to infiltrate because there were some very good science fiction comics done in the 50s. So even the very snobby science fiction fan community had to admit that, "Well, these adaptations of Ray Bradbury are pretty good."

That started to cross over from there. And then, as we were talking about with Stan Lee running the letters, not only did he run the letters—and DC did this too—they would print the addresses of the people that wrote the letters so that other people reading the comics would know who the other fans were. They would start writing letters to each other and started creating this informal network.

Around the same time, collectors were starting to recognize that older comics were valuable artifacts. They weren't treated especially well. Finding a first Superman comic in good condition might be worth a hundred bucks. And when the first comic sold for a hundred dollars, it was front-page news. Newspapers covered it as, "Wow, there's gold in your attic." And so those kinds of stories are guaranteed to pull that stuff out of the woodwork.

So the cons arrived in that period to gather the fans together in one place, create a flea market where you could buy and sell comics and collectibles, and it was a place where the fans could meet the artists. Because the poor artists were sitting in their basements doing this stuff. They had no idea people were reading them or taking them seriously. They were afraid to admit to their friends that they did comics. They would tell people, "Oh, I write children's books." They would say anything but comics. And so getting them out into the light and realizing, "Oh my gosh, all of these people know my work and appreciate it," it was good for the business, it was good for the fans.

It became this kind of thing. And if you were one of those weird people that liked comics into your teens and 20s, this was a place where you could go and meet those other people and hold your head high. You wouldn't have to pretend that you're too cool for all that stuff. You would get in with your people, and you would be saying, "Who's stronger, the Thing or the Hulk?" And these arguments could go on all night. And that created a lot of community.

How San Diego Comic-Con Emerged as a Leader

Andrew Mitrak: So, these comic conventions emerge out of sci-fi conventions. San Diego wasn't the first one, but eventually, it became among the premier ones, or at least the premier one in the US. So how did it establish itself as the leader?

Rob Salkowitz: Well, at first, it absolutely wasn't because the center of the comics publishing industry was New York. But in the late 1960s, Jack Kirby, the great artist for Marvel and later DC, moved from New York to the LA area. So he was on the West Coast, and a community of fans and people and other artists and professionals started to form in the West Coast. So several groups of fans in the San Diego area organized this show. Originally, it was nothing special; it was a couple of hundred people. They had trouble getting it off the ground. It was very informally organized.

There was a guy who was a veteran of other shows in Detroit and places like that that knew how to run a convention, and he kind of took these folks under their wing and turned it into a more regular, professional show. And in the mid-70s, the New York show started to peter out a little bit. The organizers of them, they couldn't get the East Coast shows quite off the ground. And so, here's San Diego out here. Let's go out there.

Also, the fact that Star Wars used San Diego in the mid-70s as a test market, and then Star Wars became the biggest thing in the universe when it came out. And every fan in the world was interested in that. All of these other, the proximity to Hollywood made it very easy for anybody that had a genre or fan-oriented or comic-oriented—there weren't that many of them, but shows that would appeal to this fan base—just get in the car and drive down to San Diego. It's a lot easier than flying all the way to New York.

The Rise of Comic-Con and Hollywood

Andrew Mitrak: So, Star Wars... San Diego Comic-Con starts in 1970, right? And Star Wars is '77, is the first one?

Rob Salkowitz: So '76 is when they appeared at Comic-Con, and then the movie came out in May of '77, I believe.

Andrew Mitrak: Okay. And so, do you know what inspired George Lucas or the producers or marketing team behind Star Wars to do that? Because it's not exactly obvious, right? It's not an existing IP that comic fans know. Was it just some intuition that, "Hey, this is kind of a nerdy movie"?

Rob Salkowitz: There's a whole story with this, which I don't know all the details of, but you can find it. I mean, this story has been told accurately somewhere. But what I understand to be the general outlines of it is, number one, Lucas was a comics fan as well as a sci-fi fan. There are parts of Star Wars that are very directly influenced by Jack Kirby with Doctor Doom and the New Gods and, "Luke, I am your father." That whole stuff comes out of comics that people would have been reading in the early 70s. So how that connects up to the fan base is pretty simple.

Also, it was modeled on Flash Gordon and these old serials. Well, one of the things that people did at the Comic-Cons was they would screen these movies because we didn't have videotapes, we didn't have those kind of things. So people would get out their old 16mm films, and they would show them at Comic-Con. It's one of the rooms—if you couldn't afford a hotel, you could just sit in the movie room all night and watch King Kong and bootleg Japanese anime from the 60s, all this crazy stuff they would screen there. So fans were used to seeing movies and movie-oriented stuff, and if you were interested in that kind of science fiction and that kind of thing, it was totally in place at a comic convention.

Andrew Mitrak: So after Lucas did this with Star Wars in '76, '77 era, did Hollywood start showing up to every Comic-Con, or did it take a little while for Hollywood to have a bigger presence?

Rob Salkowitz: It took a while because the people that were running Hollywood at that time were from the era that looked back on comics as trash for kids. Even if there were people that took it seriously at one level, the other formative experience for a lot of these guys was the Batman TV show of the 60s, which was played for laughs. It was basically making fun of how stupid these characters and these comics are, how ridiculous it's the same story every time, and all that stuff. So what was burned into their minds is that comics are low-grade stuff for idiots and juvenile delinquents, and the best we can do is make fun of them.

And so, you get a movie like Superman: The Movie, which is a great movie and didn't take that view at all, and a lot of comic fans, to this day, it's one of their favorite movies, even though the visuals weren't quite good enough. So there would be some stuff there, but the people that were running Hollywood, the TV executives, and the people making those decisions took no notice of that.

Milestones in Comic-Con's Growth

Andrew Mitrak: So, when you look at the last 50 years or so almost since Star Wars to today at Comic-Con, what have been the major milestones or inflection points of its growth? Specifically with the marketing angle and media blitz of the growth, because I'm sure it probably had some organic growth of comic book fandom and all that, but as far as it being seen as a way to exploit this space and market our product to them in a big way, how did that change over the years?

Rob Salkowitz: I think there were three, let's say, intermediate steps between here and the big explosion. The first one was when comics started getting distributed in comic shops instead of on newsstands. So on one hand, comics became less of a mass medium. On the other hand, the material and the fans and the culture of the comic book shops was creating a subculture that was much easier to zero in on and say, "Hey, you're at the comic shop every week, come to our convention. We're having a convention in your town, we're having a convention in San Diego," whatever. So it captured the hardcore fans. Instead of having to look everywhere for them, you had one place that you could look for them.

At the same time, a new generation of creators that was more ambitious was doing stuff that wouldn't be commercially viable unless they could take it directly to the fans first and say, "Hey, take a look at this cool graphic novel I'm doing." Nobody knew what this term meant. "We're doing a comic that's a whole book." You couldn't—it'd be very hard to just take that out to the market at large. You had to sell it to the people that you knew would buy it in order to make it commercially viable.

So, as comics became more serious, you get to 1986, which is the year that you had Watchmen, you had The Dark Knight Returns, which was a very serious Batman story, and then you had Maus, the Holocaust memoir by Art Spiegelman. These things all came out at the same time, and the mass media all suddenly was like, "Oh, comics aren't just for kids anymore." You would see these dumb headlines that were talking about that.

So, Alan Moore, who was the creator of Watchmen, came to San Diego, and it was this huge thing. I mean, it was like the Beatles coming to America. He is British, it was a long trip, and it didn't go well. He got mobbed. He was totally freaked out, and he has never come back to—he very rarely appears at conventions or anything like that anymore because of that.

So, Comic-Con kind of pivoted from being a place just for where fans meet to a place where some really interesting, cutting-edge content and creators and also independent publishers were looking for people to do comics. All the fans that wanted to see the creators would go to Comic-Con because all the creators were there to see the publishers. And so it created this snowball effect that was moving on.

And then the last thing that happened in terms of San Diego that was important is that the convention center expanded in capacity. The first year that I went was 1997, which was the last year when it was just the original building. And you could fit 40,000 people in there, which was large. Like, 40,000 comic fans in one place, oh my god, that's crazy. Then the next year, they opened Hall D, and then the next year they opened Hall E. And then by some time in like 2003, 2004, they had the entire convention center open end-to-end, and you walked in there and it just took your breath away. You could not see from one end to the other. And so the scale of it just became like, "Oh my god, this puts everything else in the rearview mirror."

And then people were like, "Oh, I see." And news crews would start showing up. So news crews would be covering it because it was this big, crazy event. And then when news crews show up, ah, earned media. Let's get back to marketing here. These are impressions that you don't have to buy. You can, if your banner is there, if your stuff is there, and people talk about it on your behalf, they're going to take that message out to the audience. And so entertainment media—as a speaking as an entertainment writer, we are a lazy bunch. If there is one place that we can go to get all the stories, we're going to go there. So San Diego became that place. And so all the media is there. When all the media is there, that means, "Oh, Hollywood, we should show up there because we'll get all this free exposure." Hollywood starts coming, and then all of these fans who don't even know about comics or anything like that, it's like, "Oh my god, like Tom Cruise is on stage at Comic-Con, or Arnold Schwarzenegger," or the top of the A-list people would show up in person, unannounced at this event, and it would just blow people's minds. They would be like, "How could you not want to be in the room for that?" And so that's how it unfolded into this gigantic extravaganza.

The Dawn of the Modern Superhero Blockbuster

Andrew Mitrak: That last phase—I didn't realize that the logistics of the event and the space and the location itself expanding really did seem to coincide with right as superhero movies came to dominate the box office. And it seems like it's the past 20, 25 years or so that they've really been not just dominating the box office, but also being such a big part of pop culture more broadly. And of course, a lot of this, I'm sure has to do with some rights and also some of the tech and CGI capabilities happening to coincide, and now you can do a Spider-Man movie that looks as good as that one does.

Rob Salkowitz: That's exactly right. So it was two things. It was number one, that the tech finally got good enough that what you saw on the screen was as good as what you saw in your mind when you were reading the comic. As hard as they tried to make comic book movies look convincing—the Batman movie from the 80s, great-looking movie, well-directed, Jack Nicholson's in it, but it falls a little short. God help you if you try—they tried to do a Fantastic Four movie in 1993, and it's not quite... So getting it to look not ridiculous and the effects to get good enough, and also the video games to get good enough, so that when you had the platform game tie-in to the movie, that became another source of big money.

But the second thing that happened is that a lot of the leadership in the studios started to transition generationally. And so out were the old guys that were like, "Eh, comics for kids." In were the people that read Marvel Comics in the 1960s, that read comics in the 70s and the 80s, and knew what they were capable of, knew that these stories, properly told, could be way better and not condescending and not campy and stupid, but actually be the basis for really good storytelling. And so, the quality of the product improved at the same time that the means of promoting the product arrived. And that was two things that happened together that made it happen.

Evaluating Comic-Con’s Role in Box Office Success

Andrew Mitrak: When you think of superhero movies, they've just been the dominant money-maker at the box office over the last 25 years or so. What do you see as Comic-Con's role in this? Is it Comic-Con, is it the movie itself, is it a little bit of both? Because not everything that's activated at Comic-Con—and even if it's warmly received... I was there, I was at Comic-Con when Scott Pilgrim was promoted, and everybody loves Scott Pilgrim at the Comic-Con. And it was a good movie, it was Edgar Wright, who's a great director and really well-made, but it didn't quite break through to the mainstream necessarily as much as you might have hoped, given the Comic-Con reception. But then other things, like the whole cast of The Avengers is at Comic-Con to announce the first one, and that becomes the biggest franchise pretty much ever. So what's your model on what breaks through and what is Comic-Con's role in helping it break through versus what sort of is just popular among the die-hard fans who are attending Comic-Con?

Rob Salkowitz: It's wonderfully unpredictable. If there was a science to it, then practically there is at this point, and that's partly, I think, why the performance and the inspiration and a lot of these things has fallen off a little bit, because it's like, "We've picked the lock, we know what makes it work." But I remember being at a panel in, I don't know, 2005, 2006. So there were these adult-oriented comics, mature subject matter stuff that DC was doing on a line called Vertigo. And they had a character called John Constantine, who was this cynical, British, supernatural detective modeled on Sting. But the British-ness of this character was fundamental to what the appeal was.

So they're at the Vertigo panel, they're announcing the John Constantine movie. And Karen Berger, who's the editor and mastermind of Vertigo Comics, is up there and she says, "Yeah, we're going to do a John Constantine movie!" And the whole place blows up. And she says, "And guess who we've got to play John Constantine?" And it's like, "Keanu Reeves." Silence. And you could feel the blood drain out of the faces of everybody on that stage. It's like, "Wait a minute, don't you guys like Keanu Reeves? Like The Matrix?" It's like, "Yeah, but not for that! What are you thinking?"

He cannot do a British accent at all. He's become a meme and more beloved now, also, but at the time, he wasn't quite who he is. And it's like, if you swing and a miss, it's too much. If it's the Watchmen movie that Zack Snyder did in 2008 that was literally a page-by-page adaptation of the comic, because he had so much reverence for the source material, he didn't want to do anything different from what was in the comic. Well, as great as Watchmen is, by that time, it was a little bit dated, and there were some things that they probably should have done to make it more interesting or to realize that you're not in comics, you're in a different medium.

And so there's a bunch of creative missteps that you can do, and comic fans will sniff that out. The people at Comic-Con who are sophisticated, used to watching a lot of media, they won't let you get away with those kind of things. And sometimes it goes wrong. But the other thing that Comic-Con did is it exposed a lot of properties that you wouldn't have thought of to make movies out of by these producers that were coming there. And they thought that they were looking for Marvel and stuff like that, and they end up with Hellboy, or they end up with The Walking Dead, other properties that may not have been top of anybody's list and suddenly they become very, very popular.

Andrew Mitrak: I think it was Sony who retained Spider-Man and X-Men and sold away Iron Man and all the rest for pennies on the dollar as far as the rights go because they didn't...

Rob Salkowitz: Marvel was in bankruptcy in the late 90s, and they sold Spider-Man to Sony, and they sold X-Men and Fantastic Four to Fox, I believe. That's right. And then the ones that they were left with was Iron Man and Thor and Captain America, and nobody thought, "Those are the third-tier characters." And Marvel really bet the house on being able to do that right. They actually raised money and started their own studio. The origins of Marvel Studios is actually pretty interesting, how they did that, because it was not obvious at all that they were going to be successful. But at the end of the day, they knew their own properties better than anybody else did, and they just knew they had some very good casting that helped also.

Key Marketing Takeaways from Comics History

Andrew Mitrak: Most of us are not marketing comic book superhero movies. I'm wondering what lessons there are and what takeaways there are for marketers. What can we learn from the history of marketing of comic books or Comic-Con itself as far as drawing lessons and how to sort of apply them to other forms of marketing?

Rob Salkowitz: There's all kinds of things that comics as a medium and as a culture were ahead of the curve on. We talked about the role of people like Stan Lee in creating a brand around a unique and memorable and personal voice. It took marketers a while to realize that that was a good way to do it. And it didn't even matter what it is that you were trying to market. If you could get people to identify with your brand in that way, they would do anything for you. They would become your ambassadors. So comics figured that part of it out.

Comics figured out the—because of the way the medium and the business worked, they had to sell you an issue every month, and they needed to keep you interested month to month. So you needed things to be interesting enough to change a little bit, but not change so much over time that you would get so far away from the premise of your character that you wouldn't even recognize it. So this idea of continuity and stasis together as a storytelling vehicle to keep people engaged, and then also this idea of continuity where you were telling big stories and not just creating a story, but you're creating a whole universe that gave you opportunities to explore backstory and characters and history. And then to take it not just from one medium, but to all kinds of different media...

If you look at the way the television worked in the up until, say, the early to mid-90s, every time you turned on the TV and watched an episode of something, it was as if none of the other episodes of that show had ever existed. Then, as it became possible, "Oh, we can rewatch the season on VHS or something like that," you started to get these season-long story arcs, like in Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Star Trek: Deep Space Nine or things like that. And it became—you'd be able to build these franchises starting with one thing and then moving over to another thing. Comics had been doing that, had been doing that for 40 or 50 years, and a lot of the same storytellers that were doing it successfully in comics moved over into other media to do that. And I think marketers can learn from, when you're trying to build a brand, when you're trying to build a line of connected products or create affiliated brands or tell big stories, there's a lot of lessons that you could learn from how to weave these things together.

As you know, I teach a class in transmedia storytelling, and that's one of the principles of it, is how do you keep people engaged across these different media? How do you make your story accessible to different audiences in different ways, but all have them funnel into the same place? Marketers are trying to do that every day. So it's a little bit of a bank shot. It's not like, "Oh, study this comic, and you'll know how to sell IT services or something." But the fundamental building blocks are there, and the advantages that comics have been doing it to a very critical audience. So it's been wind-tunneled and tested in an optimal way before it hit the streets. And they've created this culture, just like this great petri dish for trying out all of these different things. So I think a lot of brands and even just the idea of a convention itself has been adopted across a lot of industries that are using the Comic-Con model in ways that I don't think the original founders would have intended or recognized.

Andrew Mitrak: Some of my top takeaways might be the power of in-person events and in-person gathering. There's some itch that we have. I'm sure a lot of comic book fans are introverts and don't necessarily gather, but there's something about magic of people wanting to connect in person. And as a marketer, in-person events are super hard. There are all these logistics and moving stuff around, but it can be worth the effort if your target audience is there. That's one. Obviously, appealing to your superfans and creating magical experiences and treating your fans and showing respect for that core group that will spread the word. I think there's also some power to physical materials. A comic book is a physical thing, and so much of advertising and marketing is all digital, and that just having something that's tactile and there in front of you—I'm sure you can read comics on your iPad or on your book, but there is still something that's nice about a printed material.

Rob Salkowitz: The scarcity angle and the fact that the best way to get people to buy your product is to tell them, "I'm sorry, there's not enough, we don't have any, wait in line, maybe you'll get one." Creating that sense of scarcity—we live in an age of digital abundance. Every digital thing is identical to every other digital thing. So having something that is unique, that's physical, that's collectible, that's hard to replicate, and that's exclusive—yeah, brands could totally learn from that.

Andrew Mitrak: I think one other takeaway I'd have also is that no matter how big something is, it can always seemingly get bigger. Even if you think 40,000, "Who could ever need more than 40,000 people at a comics convention?" And I remember when I was taking your class 11 years ago, I thought, "Oh gosh, superheroes are at their peak. They're already going to Guardians of the Galaxy. Nobody's heard of that. They're already like..." But they've been so much bigger. It can get than where you think it is, even if you're thinking it's at the top. Things can always get bigger. There's room for more, just because there's so much creativity within storytelling, and the world is such a large, addressable market that things can always get bigger than you expect.

Rob Salkowitz: Absolutely.

Andrew Mitrak: Well, Rob, it's been so much fun taking this tour of comics history, marketing history, Comic-Con marketing history. Where are the best places for listeners to find you online and read your work?

Rob Salkowitz: Yeah, so I write for Forbes, and you can find my stuff there, probably five pieces a month, something like that. So you can search for me through the usual ways. If you follow me on BlueSky @robsalk or on LinkedIn, is a good place for connections. You can find my books sold in Amazon. So the main book that's the focus of this conversation is called Comic-Con and the Business of Pop Culture.

It came out in 2012, and unfortunately, it got enough stuff right that it now reads like, "Oh, that's totally obvious." But at the time that I wrote it, a lot of this stuff was not totally obvious. So that's where that's the genesis of a lot of the stuff that we were talking about. I've also written some other books on other business subjects that people might be interested in.

Andrew Mitrak: Well, yes, thanks Rob. I'll post links to all those in the show notes and in the blog that accompanies this post. So thanks so much for your time. I really enjoyed this conversation.

Rob Salkowitz: Thanks for having me. I thought as my student that you'd gotten your fill of it 12, 15 years ago, but apparently not.

Andrew Mitrak: There's always more to learn about this, and I think checking in every 12 to 15 years sounds okay to me. (Laughs) I hope you have a great Comic-Con this year.