A History of Marketing / Episode 22

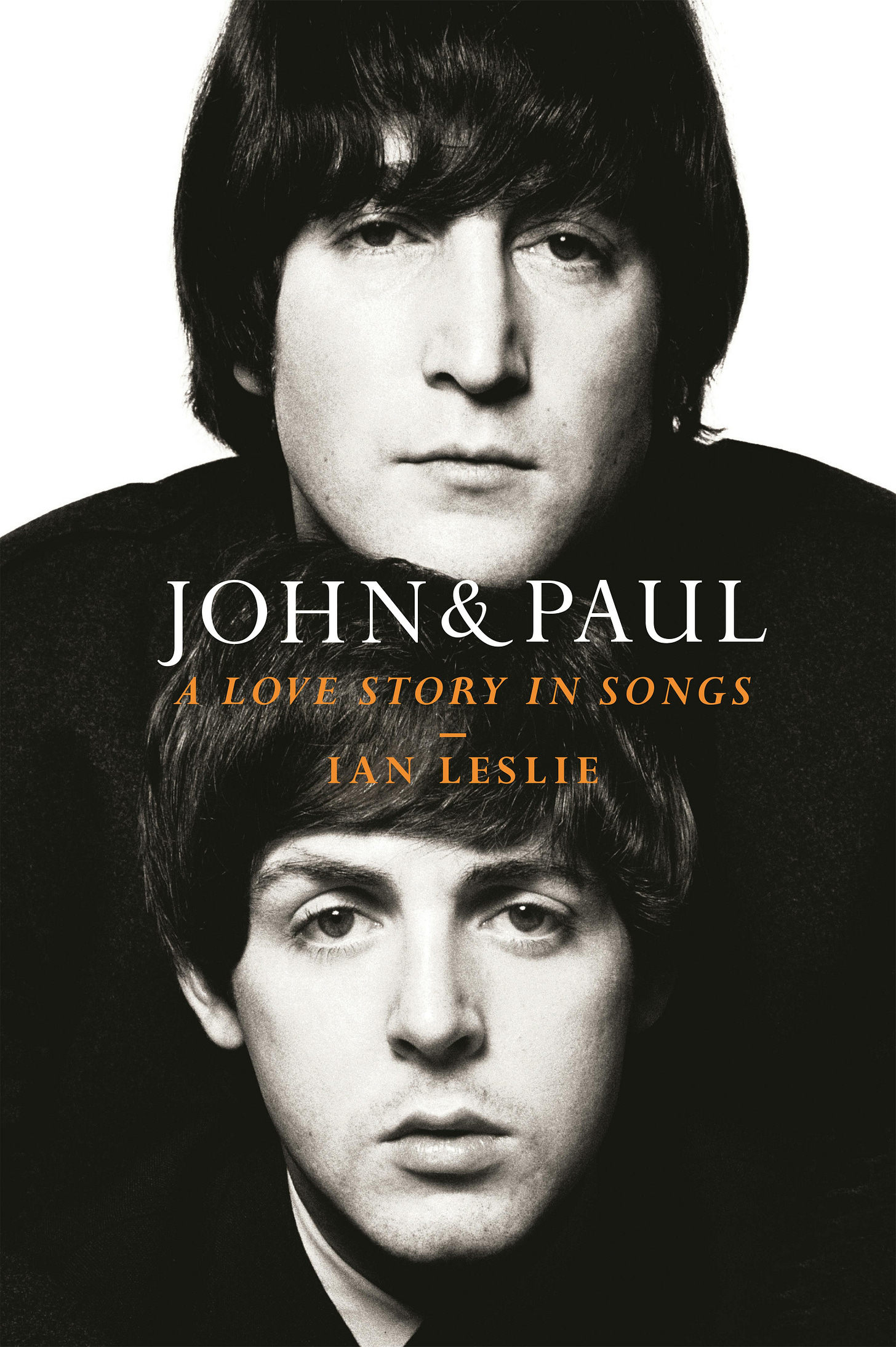

Today marks Sir Paul McCartney’s 83rd birthday. To celebrate, I’m publishing my excellent interview with Ian Leslie. Ian’s the author of the New York Times bestseller: John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs, published in April.

It’s my favorite book I’ve read this year. It tells the story of the creative partnership at the heart of the most influential band in history. I’m pretty familiar with Beatles’ story, but this book tells the story in an intimate way. I laughed, I cried, and I didn’t want to put it down — except to stop and listen to the songs.

Now you might be wondering, “That’s nice, but what do the Beatles have to do with marketing history?”

Great question! For one, as the best-selling musical act of all time, the Beatles knew a lot about marketing.

They deliberately crafted their image, they mastered media relations, and they engaged their fans with tactics that were way ahead of their time.

In marketing speak, the Beatles created a new category and they dominated that category as the brand leader.

This episode analyzes the marketing masterclass that was The Beatles, and Ian Leslie is the perfect guide. Not only is he a great biographer who's immersed himself in the world of The Beatles to write John & Paul, but he's also a marketing veteran who spent the first part of his career in advertising and brand strategy.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Ian Leslie is behind the popular Substack The Ruffian. (I am a paying subscriber and highly recommend it!) Prior to John & Paul, Ian also published a viral essay “64 Reasons To Celebrate Paul McCartney.”

Now here’s my conversation with Ian Leslie.

Note - I use AI to transcribe the audio of my conversations. I review the output but it’s possible there are errors I missed. Parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity.

John & Paul: A fresh look at the best-selling musical partnership in history

Andrew Mitrak: Ian Leslie, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Ian Leslie: Hello, Andrew. Good to be here.

Andrew Mitrak: Great to have you. I loved reading your book, John & Paul. You told the story of The Beatles, and of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, in such a fresh and intimate way. I just devoured this book. I made my wife read it, and she loved it, and we've had the joy of just talking about this book, revisiting The Beatles' music together, and listening to some of Paul's solo work. So it's been such a joy, and I just wanted to start by saying thanks for writing this book.

Ian Leslie: Well, I'm delighted to hear that. Thank you very much.

The Beatles as business innovators

Andrew Mitrak: So, given your background in marketing and in business, when you were researching and writing this book, did you ever find yourself, either consciously or unconsciously, analyzing The Beatles through the lens of marketing, promotion, and business strategy?

Ian Leslie: Yeah, there were several points where you reflect on how certain decisions impacted their success or slowed it down in some way. And apart from anything else—apart from the creative and the artistic story, which is obviously where I focus in the book—it's an incredible story of innovation and creating a whole new market. You know, we talk about inventing the future a lot. I mean, these guys really did invent their own future because they weren't satisfied by what was around them.

First, a big brand in their home market, and then they become a huge global brand, and they're absolutely dominant. And it turns out to be an enduring brand, too. It's not just for a couple of years. And they're creating a new category, or new categories, as they go, both in terms of the overall category of being a pop group that isn't just a flash in the pan. And also products like the album, which hadn't really been a best-selling product type until they came along. So yeah, it's an astonishing story just from a commercial point of view.

‘The Beatles’: The best or worst band name ever?

Andrew Mitrak: I think for me, one of the first parts of the story of establishing the brand was actually just the selection of their name. The name "The Beatles," I think, is just the perfect band name.

And it sounds so perfect, it almost seems like it just came from the heavens organically, but it was a really consequential and deliberate decision they made. And they tested a number of names. Prior to The Beatles, of course, they were The Quarrymen to start. But do you have any thoughts on or reactions to their approach to naming and the name "The Beatles" itself?

Ian Leslie: That's interesting because it's interesting that you see it as the perfect name. And I'll invite you to expand on that in a minute. Because I could see it both ways. I mean, obviously it worked out pretty well. But you might say it's like the worst name ever, as well. And it's almost like these two things are inextricable. It's either going to be the worst or the best. It turned out to be the best.

But let me just put the case for the worst name before we get onto the case for the best. It was not a recognizable type of name, if you see what I mean. Basically, the stars of the time in the late '50s and early '60s were solo stars or a solo star plus a backing group. So you had your Elvis Presleys, and you had your Cliff Richard and the Shadows. Right? So you had your X and the Ys. And the idea that you could just have "The Somethings"... you know, or Buddy Holly and the Crickets. But the idea of just "The Crickets" or "The Somethings," it wasn't really a thing. It wasn't really a precedent for that.

And it got The Beatles into a lot of… it slowed down their progress in a way because they were so determined not to have a frontman for various reasons, that promoters and so on found it hard to say, "Well, who are these? I don't understand. What is this group?"

And then the other thing is, it's just this really cheap pun. I mean, the stories differ on the origin of it, but something to do with maybe they took inspiration from The Crickets and they chose another insect, but made a pun on it because they were playing what was called beat music at the time. And they end up with this pretty cheesy pun. And the name had to be explained over and over again. And you see this all the way through, right up until they start becoming famous, all the promoters, all the record label guys, and audiences are like, "The Beat… The what? The Beetle? What?" And they have to spell it out. "Yeah, it's spelled B-E-A-T."

So it's this laborious thing where you have to explain it. And then once you get it, you're like, "Oh yeah, that's The Beatles. I'm in on it." So, this I think is where we flip into your "best name ever" case.

A big improvement over “The Quarrymen”

Andrew Mitrak: The case for it being the best name is – I've had the chance as a marketer to name a couple of companies and products– And I think what you look for is you want something to be short, right? Aside from "the," it's a couple of syllables. It's easy to pronounce. It's unique and it's clever, but it's not like some weird misspelling. Beat, B-E-A-T, right? It's easy to spell. Also, I know it existed 40 years before Google and SEO, but if I was to name a thing today, it seems very SEO-optimized, which is kind of funny.

And also, it enables them to grow... you know, they were The Quarrymen, which sounds like a very local, schoolboy kind of name, right? I think it alludes to the school they attended, right? And I couldn't see The Quarrymen having Quarrymen-mania, right? And Quarrymen merchandise being a global phenomenon. It's a very… a hard name to spell.

So "Beatles" just seems to have a certain universality to it. They also feel like they're a group, which is really enabling their success. And it was really prescient of them to not be "Long John and the Silver Beetles."

And also it's more distinct. Something like The Animals... it sounds a little vague though, right? It doesn't sound as unique and ownable in a way. So that's my bull case on the name The Beatles.

A high risk branding bet that paid off

Ian Leslie: So, the way I see it is, names like this that are not descriptive of the product in some way, that are just sort of odd or weird and need explaining, they're like high-risk bets. You know, they can easily go wrong, which is why a lot of, or maybe most, brands when they're naming their product—brand managers—they choose a name which explains a little bit what the product is. So, say this is like Microsoft versus Apple. I mean, Microsoft… it's actually a bit of a weird name because they were weird guys, but at least it was something to do with microcomputers and software. I don't exactly know what the derivation is, but you get the general area. Whereas Apple is just like, what? It's got nothing to do with computers. I don't even get it. They're both successful, obviously, but Apple's probably the cooler, better brand name. And it paid off in spades, right?

So yeah, The Beatles chose a name which isn't descriptive. It's not "Something and the Somethings." It doesn't tell you anything about them, really. It's an odd name. But once you're in on the secret, then you feel like you're in a club. And so it helps to generate this early community of fans and community, which a lot of startups really look for when they're in the first year of existing. So I guess there's something in that.

Creating and managing the Beatles’ image

Andrew Mitrak: So, they had this really distinct image in their early days: the mop-top hair, the matching suits, the Beatle boots. Literally iconic from head to toe, from their hair to their boots. So, would their manager, Brian Epstein, deserve a lot of credit for this? Or do you think this was leaning into some of The Beatles' organic tastes of fashion? What are your thoughts on the initial image they created?

Ian Leslie: Yeah, it's an interesting question. Before they met Brian Epstein, they had a… they always had a strong look. They always looked… and they looked very different from the other groups that were around. The other groups tended to wear flashier gold lamé suits and look very much like they were in show business. And The Beatles went for a scruffy leather jacket… It looked like they were just thrown together, but actually they all wore the same thing. And it was all definitely part of their image as scruffy upstarts.

Now, Epstein comes along and he's like, "Well, you're not going to get on TV if you look like this, right? You have to find some compromise here." And looking back on it, Lennon was like, "Oh, he made us sell out," and so on. But I don't think that's quite right. They already looked a bit sort of try-hard with their leather jacket rockabilly look. It looked a bit like they were trying to be throwbacks to the 1950s. There was something a bit, "Ah, we've done that now, guys." So I think they were already ready to move on.

And the other thing is, they took his cue to smarten up, but then they chose really cool suits. Like Yves Saint Laurent-influenced, collarless jackets and narrow trousers in cool materials. So they found this… it was a bit like a Motown group, really. So they find this way of saying, "Okay, I understand the goal now. The goal is to break into mainstream media in effect, and you can't do that if you're dressed for small clubs in Liverpool and Hamburg. But also, I don't want to just be like all the other groups." They've always hated being like all the other groups, right? We're never going to do that. "So why don't we find our own way to smarten up?" So that's the interesting lesson there, is like, you're going to compromise with the audience or the market in some way, but that doesn't mean becoming less individual. You just find a new way to be individual.

Andrew Mitrak: It also strikes me that their look and their image— I think of The Beatles as the black-and-white era Beatles and then the color era Beatles. And that there's, you know, sort of A Hard Day's Night and there's Help!, right? And Help! and beyond. And that this black-and-white image, it was the 60s, but a lot of things felt like the 50s still. And that it somehow just seemed to look good on black-and-white television, just their silhouettes and their image. And it feels like they were really attuned to the actual media that was presenting them.

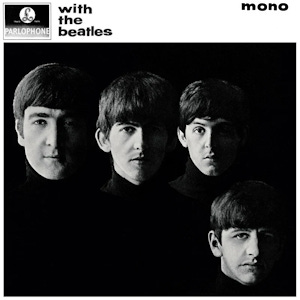

Ian Leslie: Yeah, and you can see that in the album covers as well from pretty early on with With The Beatles and Beatles for Sale. And they are opting for a kind of moodier look. They don't want to be just these grinning guys or these glamorous pop star image. They're doing something new, and it's a bit more European. It's influenced by Germany and, you know, by Astrid Kirchherr and by French culture. And more to the point, what they're doing now is taking control of their brand.

The Beatles as a vertically integrated brand

Ian Leslie: You think about the fact that Lennon and McCartney were writing their own songs and singing and performing and then recording them. That was pretty much a new model, certainly for a group. And they were effectively… because before that, you had groups, and then you had songwriters, like Tin Pan Alley songwriters. And the labels would distribute the… they would match the songs to the group or to the solo act. They'd say, "Okay, try this song, try this song, try this song." And very quickly, The Beatles were like, "We don't really want to do other people's songs. We'll cover rock and roll songs or soul songs that we love, but we're not going to accept other writers' songs because we've got pretty good songwriters."

So they vertically integrate the creation of the content and the distribution of the content, if you like. And also the front end of the content, not just in the recordings, but in the actual packaging of the product as well. So they take control of that creative process from beginning to end. They do that pretty quickly, really within the first year of getting famous. So it's an extraordinary amount of very audacious act of confidence and a land grab which opens the way for this whole new category, in effect.

Andrew Mitrak: It's just astonishing the intuition they have, the boldness of it, and that they were able to get this control. And they were just little kids, like they were 20, 21 in this era. And they have such great intuition about so many things. Of course the writing of the music and the performing of the music, which is at its core, but then also their image, and as you said the vertically integrated end-to-end ownership of the process. Not only really good musicians, but also really good at a lot of other things.

Ian Leslie: Yeah, I mean, I still don't really understand where they got that confidence or that audacity from. But I think it is partly to do with just having been together and experienced so many amazing experiences, both traumatic and joyful and hard and fun together in those years as teenagers in Liverpool and then in Hamburg, that they felt, you know, John and Paul in particular, but the whole group, really felt kind of indestructible and had a sense of, "Well, you know, you take us or you leave us." You know, they weren't absolutely against compromises, as we've seen in the sense of, you know, in terms of how we dress and so on. But they did have this sense of themselves as artists. They might not have used the word, but they did think of themselves as artists rather than just entertainment stars who were going to do music for a year and then become game show hosts, which was the conventional career route for most pop stars.

‘Beatlemania’ and the merchandising machine

Andrew Mitrak: I was watching the Beatles 64 documentary, this is the one that was produced by Scorsese and I think it's streaming on Disney. And it struck me that when they came to America in February of '64, their fans already had all the Beatles merchandise, seemingly. They have this clip in the documentary of people having the mop-top wigs and buttons and knockoff Beatle boots and all this merch that they had. And it's like, these people, they just came onto the scene. I think their music had probably been on the radio in the months preceding their visit, but still, it just seems like, just operationally, how did they get all this merchandise produced so quickly? I'm sure it was some mix of knockoffs and maybe some legit merchandise. But do you have any sense of the merchandising machine that surrounded The Beatles in this era?

Ian Leslie: I don't know, it's a good question. I'm not an expert on that side of things. But I think a lot of it was not official merchandise. I think their record label, Capitol in America, very quickly did a big merchandise effort when "I Want to Hold Your Hand" becomes their first smash hit in America. And then they did the wigs and they marketed them as these four mop-tops and so on. But then I think, America being America, lots of small entrepreneurs just sort of pitched in and did their own thing. And the thing is that they hadn't tied down the legal rights to that and the commercial rights to that merchandise.

And it's one of the things that Brian Epstein gets criticized for most harshly in retrospect, is that he didn't tie down merchandising deals and therefore left an awful lot of money on the table. How far he was expected to have foreseen that boom in merchandise, I'm not totally sure, but it's true that they weren't making a lot of money from this stuff.

‘A Hard Day’s Night’: Expanding to the big screen

Andrew Mitrak: There's A Hard Day's Night. I don't know how it was also released in 1964 or how they had the time to film such a good movie. But they make this film, A Hard Day's Night, which stands up really well. And did they see films as sort of a way to promote their album sales and their concert tours? Or did they see this film as an art form in itself that they wanted to really break into? What was their approach to where film fit in?

Ian Leslie: Well, I think it was very conventional at the time for pop stars, you know, Elvis Presley most famously, to make movies as an extension of the brand. And yeah, as another way to distribute your content and another way to meet your teenage fans.

So that wasn't innovative, saying, you know, "Oh, you know, we're pop stars, now we need to do a movie." The innovative or the thing that was different about them was that they decided it would be good.

You know, we can put it more like, you know, they wanted it to be innovative or artistic or creative. But basically, they were just like, "We don't want to do a crap movie because we think all these teen pop movies are crap."

I don't know exactly how they chose Richard Lester, the director, or the writer, [Alun Owen], but the writer had spent time in Liverpool and was part of the beat scene, he got them. And so they helped choose him. But they end up with this team, including a cinematographer, a brilliant cinematographer [Gilbert Taylor]… he went on to shoot Star Wars. You know, so he's probably responsible for the two most powerful visual properties of the 20th century. So they had an amazing team and so, you know, some of that is talent that was around in Britain at the time. Some of it is luck, but a lot of it is The Beatles' driving force, which is, if we're going to do this, we want it to be good. We don't want it to be mediocre and embarrassing. And you can get a long way with that attitude.

John, Paul, George, and Ringo: A whole product range

Andrew Mitrak: There's a quote that you wrote in your book on A Hard Day's Night or this era, and I'm going to read it back to you because I like it a lot.

"After A Hard Day's Night, The Beatles had distinct personas in the minds of the public, vividly drawn but crude cartoons. Ringo Starr as the doleful clown, George Harrison quiet but deep. John was the Beatle with the sharp tongue and scathing wit. Paul, the cute and charming one. The Beatles conspired to create these masks, but by 1966, they were wary of them."

And I just think this is an important passage because it sets up a lot, but what stood out to me is "they conspired to create these masks." Why did they conspire to create masks? Could you unpack that line?

Ian Leslie: Well, they realized, together with Brian Epstein, that being this unusual type of group which didn't have a lead singer could actually be… on the one hand, it made them difficult to comprehend within the music industry, but once you get over that barrier, it actually presents this huge marketing opportunity. Because then you can have all four characters, and all the fans could choose their favorites. And you have this whole product range, if you like.

They wouldn't have put it like that, right? But certainly, Epstein was central in, before they were famous, at the Cavern saying, "You know, make sure we give George a turn at the microphone. I want you swapping between John, Paul, and George."

And when they're on stage, you see Ringo raised up, so Ringo's not this anonymous drummer, he's very much part of the visual presentation of the group. So in that sense, it was a conscious presentation. And then when it comes to the film, obviously the film is this heightened version of Beatlemania, a comedy, ironizing version of what's going on with them in that first year of fame. And it creates these caricatures which are rooted in some truth about what they're like, but are not the whole deal. So yeah, they're very much part of creating that story. But obviously, it's somewhat in tension with their mission as artists and their desire to be individual human beings and not just fodder for the entertainment industry.

Andrew Mitrak: It’s useful to have this shorthand or a “crude cartoon” but down the line it does put them into a box and plant the seeds for music criticism of their solo careers, and the legacy of John vs. Paul as that becomes a central point to your narrative.

Ian Leslie: Yeah, true.

Engaging super-fans with Christmas records

Andrew Mitrak: One of the other things they do in this era that I wanted to highlight is that they'd have an official fan club and they'd do these Christmas records.

And they'd record these, they'd mail them to their fans, and they'd be sort of lower quality recordings, but they'd have improvised jokes. And it felt like a really… if you can listen to them, I think they've been packaged on the Anthology and are on YouTube and such, but it feels very modern as far as a marketing tactic to have this this special, raw, authentic, hear directly from them, hear their improvised jokes on the recording. It feels like it was almost recorded in a living room where they're having drinks or something like that as they're recording these. And then they just send sort of their authentic selves to their fans, almost like an early newsletter. Can you talk about this? Was this a common thing in the time or is this something that The Beatles sort of helped pioneer or perfect?

Ian Leslie: Yeah, that's a great point and a great sort of analogy for how fans communicate. Yeah, they were communicating very directly with fans, weren't they? I don't know the answer. I don't think it was that conventional. I don't think they did it in a conventional way. And they were always very assiduous about looking after their core fans, I suppose. All the way through, they were replying to a hell of a lot of letters, for instance. So many stories about people coming in and seeing them after gigs or before gigs, just going through piles of fan mail and writing replies.

Making Christmas recordings and sending it to their fans they were doing that all the way through the 60s, even after they're growing their hair and being cool and doing drugs and being weird, right? They were still doing Christmas messages. There's a very amusing conversation in 1969 when they're all splitting up and they're grown-ups now and it's all so different and changed. And John is saying, "Yeah, but what are we going to do about the Christmas message? We need to get that out to our fans." They're still thinking about that. So they did have this intense focus on the bond that they had with their core audience.

And comedy was a big part of it, being funny was a big part of it, right? It's not not just about music. It's about this personal connection. And they always had that, as well as the music and as well as the image, they always had this strong personal bond with their fans that they were very keen to cultivate.

Expanding their fanbase from teenagers to everyone

Andrew Mitrak: On their fans, what's really funny to think about also is just how their fans evolved over time. That in the Hard Day's Night era, in the Ed Sullivan era, what you see mostly on the screens are overwhelmingly teenage girls, right? And I imagine that a lot of their fan mail was from teenage girls. But then pretty soon, they'd have universal appeal. Abbey Road is only six years or so later, and the fans for that don't seem like an album for teenage girls at that point. Same with Sgt. Pepper's. And they expanded their appeal with that core teenage girl audience, but they didn't limit themselves to that. Can you speak to how they thought about expanding their appeal and keeping their teenage girl fan base, but also expanding it so they weren't limited to that little box?

Ian Leslie: I don't know. I mean, I actually think that for all that we're talking about them being intuitively great marketers, which I think they were, they didn't really strategize about their audience in that way, right? So they weren't ever thinking, "Oh, we need to move on to a different audience now. And how do we manage that transition?" They really were just thinking, "How can we delight everybody now?" and "What's going to delight ourselves?" And it turned out to be the same thing to a remarkable extent.

Now, with the teenage girls, I think what's interesting about that is that the teenage girls who caught on to how amazing this music was before the rest of the country… before all the older blokes who later on took ownership of this story and said, "You know, you don't understand the music, it's all about…" Like, okay, well, you completely passed you by. And that the screaming was basically the most appropriate response to a change in music and culture that was this seismic. So I applaud all those teenage girls.

The other thing to say about this is that The Beatles never took those teenage girls for granted. They never talked down to them. They were never scornful about them. So they might have complained about the noise at the concerts now and again, but you will search high and low for interviews in which they make any mean-spirited comment about their fans. Do you see what I mean? And I think, particularly from John and Paul and George, I don't think they would ever… they ever thought in terms of, "Oh, now we need to get rid of this shallow, silly teenage girl audience and move on to the mature male…" I just think they thought, "We want everybody in." You know, this is a big tent, we want as many people in it as possible.

Andrew Mitrak: There was a quote that I had highlighted from the book as well.

"As well as female fans in Liverpool, McCartney's ballads later helped win over older generations. But the ballads were more than a marketing tactic."

And I think that songs like "Yesterday," which is just this astounding piece that stops you in your tracks, and it's not the whole band, it's Paul solo with some orchestration on the record, that doesn't necessarily feel like it's pandering to the teenage heartthrob audience, although he's the cute one. But it also has this appeal to a broader crowd than just the teens who are watching Ed Sullivan.

Ian Leslie: Yeah, absolutely. They always had this incredibly broad appeal. And so, in a way, they were the voice of a young generation, they were subversive, they were anti-establishment, rebellious in some ways, but they were always charming with it. It was impossible to resist the charm about, you know, "you just rattle your jewelry," you know. That remark from Lennon at the London Palladium was just the perfect Beatles-Lennon style remark where it's satirizing the rich, but it's kind of in a quite a warm-spirited way, you know, it's not that mean. So, they did have this remarkable appeal. And then they become really the brand leader for pop and rock music.

The Beatles as brand leaders in their category

Ian Leslie: You think about brand leaders in any category, what I learned in my marketing theory days—it's not always true—is that the brand leader can win on all the attributes in a category. It can lead on all the kind of key attributes that people care about when it comes to this product type, right? And then the challenger brands have to come in and take one of them, compete on one of those dimensions, because it's only the brand leader that can compete on all of them.

So in Andrex, we have a very famous brand of toilet paper in Britain called Andrex, and it was the brand leader for many years, and I'm not sure if it still is. And its slogan for many years was "soft, strong, and very long."

So there you have all the three things that people care about in toilet paper, right? It's soft, it's strong, and there's lots of it. And you can have those "and" kind of brands when you're a brand leader. But then if you're a challenger brand, you just want to come in and say, "No, we're the softest," right? It might not be the strongest or the longest, but we're the softest.

And that's what you start to see in the 60s because you see The Rolling Stones come in and consciously position themselves against The Beatles and say, "Well, we're not going to try and be for everyone. We are going to be the voice of the teenager versus the parent, right? The rebel versus the establishment." And we'll position ourselves against the brand leader and kind of, you know. So they opened up this space for different brands to kind of come in and take different parts of the market.

“Let’s write a swimming pool…”

Andrew Mitrak: There's a quote from Paul, I have it here:

"John would be getting an extension on his house or something, and the joke used to be, 'Okay, let's write a swimming pool.' It was great motivation. And then in the next three hours, 'Help!' appears from nowhere. And suddenly you get this idea, this is a hit, this is a good one. And you become aware that what we're doing is making money, making good money."

Not that all their songs were probably written just purely for money, but it was something that was in their mind and that they were thinking about the appeal of their music and the marketability of their music as they put it together. So it does seem like it was a conscious driver of their work.

Ian Leslie: Definitely, definitely. I mean, they always wanted to be rich, and they always wanted to be famous, right?

But I think what that comment is so revealing of is how our ideas of how to make money were flipping around this time and how kind of almost shocking it was that you could do this, right?

Because you're growing up in an era where, roughly speaking, the amount you earned was somewhat equivalent to the amount of work you put in, the number of hours you put in. And certainly, you know, their alternative careers, which were working in a factory or or maybe becoming a teacher if you're lucky, you know, you worked really hard and then you got a salary for it.

The idea that you could just spend half an hour writing a song and earn a hundred times a teacher's salary in that half an hour, because there was something so extraordinary and desirable and contagious about what you created in that half an hour, that was just breathtaking and and sort of hard to get their heads around. So I think that's what Paul's joke is about.

They realized that this thing that they liked doing anyway, which was writing songs together, yeah, they could earn huge amounts of money from half an hour's work, and then they could... I mean, that was crazy. And we're a bit more used to that idea now because we live in this kind of world of mass creativity, mass entertainment, and passive income and all these other concepts. But then it was pretty new.

Release strategy: albums, singles, and non-album singles

Andrew Mitrak: On this songwriting and song release strategy, one thing that strikes me about The Beatles is both their albums and their non-album singles, which seems like a unique thing. Well, one, most albums would usually have a few good songs and then a bunch of filler, a few good songs if you're lucky, right? There's some filler. But The Beatles' albums, especially from Rubber Soul onward, didn't really have filler. There was no room for filler. There weren't covers the same way there were on the early albums.

And on top of multiple albums a year of just great music, they'd also release these non-album singles. And some of their best-known songs, like "Paperback Writer," "Rain," "Lady Madonna," "Hey Jude," "Revolution," were never on an album, or they weren't packaged on an album. You'd buy them as a single.

What was their strategy behind this? Is it just that they wrote so much good music they couldn't even fit it all on the albums, that they were just overflowing with great hits? Or was there more of a deliberate approach to doing this both album and non-album single approach?

Ian Leslie: Yeah, you know, it goes back... I can't remember if "Please Please Me" is on Please Please Me. It's the kind of thing I should know, but I forget. But certainly "She Loves You" and "I Want to Hold Your Hand," I don't think are on albums. And yeah, you see that all the way through. "Penny Lane," "Strawberry Fields," is probably the most famous example, you know, recorded for Sgt. Pepper and then kind of, "No, we'll release these as a single." And obviously it's a single...

Andrew Mitrak: By the way, you're in England and you know the UK albums. I know the American albums, and so some of these, I think, would be on albums for the ones that I purchased as well, but they weren't on the UK albums.

Ian Leslie: …You don’t look old enough to have purchased the American version...

Andrew Mitrak: Well, I didn't purchase them back then, but I'd go to my local Best Buy and buy the CD of it, right?

Ian Leslie: Oh right…

Andrew Mitrak: Even on streaming, when I look at the US albums, which is what I probably default to on my Spotify or YouTube Music or whatever, it just always has those singles on an album. I think "Penny Lane" is on Magical Mystery Tour…

Ian Leslie: They did put them on Magical Mystery Tour. That's fine. But they were recorded for Sgt. Pepper. So they were meant to be part of that. There's a famous thing which is like, "Oh my god, what if they had been on Sgt. Pepper? It would have been even more amazing."

But yeah, but generally a lot of singles, a lot of their most famous songs are not on any albums. And their albums are really pretty good. So, I don't think this was a normal thing. I think this was them from the beginning deciding that they didn't want to rip fans off, and they wanted to kind of give fans more than fans expected.

You know, these days the cliché is, you know, "surprise and delight your audience." But it was that kind of thing. It was like, "How can we actually go further than we need to in terms of, you know, generosity and giving our audience more?" And in a way, it became a bit of a rod for their own backs, I think, because once they'd established that habit, they didn't feel like they could get rid of it.

So I think they maybe regretted not putting "Strawberry Fields" on Sgt. Pepper, etc., etc. But by that stage, they'd established the precedent. But yeah, I mean, I just think it's another beautiful example of The Beatles just always doing more than they needed to and being better than they needed to at every stage, in every aspect of their creative production.

The Beatles as PR pioneers

Andrew Mitrak: One of the other things that strikes me about them is their public relations. So much of the footage we see from them in the 60s is them in front of the press with a bunch of microphones in their face, especially in their touring years where they'd sit and everybody from the city that they were touring in would have the local media asking them questions.

They were just so witty and have this kind of meta-commentary about being interviewed in a way, or kind of there's a self-awareness to how strange it all was. And they just strike me as the folks who would do really well on social media today as well.

So do you have any thoughts on their approach to public relations and media relations and how it differed from other artists at the time?

Ian Leslie: You know, it's funny, as you're talking, it does remind me of these current debates in politics about how to present your... how to get yourself across, you know. And the contrast between the way the Democrats handle communications in the election campaign and the way the Republicans do, or at least the way the kind of Trump wing of the Republicans do it, which is much more free-wheeling and kind of, "Here I am," and unscripted and rambling on, versus the Democrats who are more conventional politicians, like, "Here's the script." And I don't want a free-wheeling conversation because I might say something wrong, right?

And The Beatles did have that kind of, like, "We're unafraid. We'll just come on and talk to you, and we'll answer any of your questions. It's fine. We might kind of take the piss out of you if you ask a stupid question, but we're not going to just do the scripted kind of delivery." And they hated that kind of artificial, synthetic kind of being a good boy in front of the press and saying the right things, just as a lot of people today hate the kind of conventional politician, you know, just being on message all the time. The Beatles never wanted to be on message. They always wanted to be themselves. And you see that in the press, in the PR as well as the music.

Where does it come from? I mean, I think this again goes back to the fact that they spent a long time together struggling to become famous for several years. I mean, obviously John and Paul and George had been together for like five, six years by the time they got famous. And they've been performing in all these terrible places. And they've just been kind of pushed together, and they've got this very strong sense of who they are. They have a very strong internal culture, organizational culture, if you like, which... and so by the time they get famous and are in front of the world's cameras, they just know exactly who they are, and they're not prepared to compromise on that. They're just like, "Well, this is who we are. We like making ourselves laugh, and we hope you're going to laugh along." And by and large, the world did.

Facing a PR crisis of biblical proportions

Andrew Mitrak: On this topic, one of the things that seems appropriate to bring up is the "more popular than Jesus" quote. And this is also an area where a band is probably dealing with something that no other band has really dealt with before, like a PR crisis about the importance of religion and comparing themselves to that. And it seems relatively like a kind of a blip.

Obviously, it's an important point if you see a documentary or in your book, it's covered, but it is something they also recovered from pretty well. How do you think they handled it or what was sort of their approach to handling that?

Ian Leslie: Well, yes and no. It was a blip, but I think it was quite a scary blip at the time, both because when they were on tour in the States and there was this whole kind of hoo-ha about being bigger than Jesus, they felt under assault. They felt sort of unpopular for the first time, or they felt hostility, real hostility towards them for the first time, which was very unsettling. And they felt a physical threat as well. There had been rumors of snipers getting into concerts, maybe someone's going to shoot us. So that was all quite scary.

And some of their concerts didn't sell out. That tour, you know, there were empty seats in those stadiums, right? Which had kind of never happened before. So I think it felt a little bit like this might be it, you know. There was some sort of sense of real jeopardy there in terms of their career.

But the way they get through it is by returning to this sense of inner conviction and determination to tell the truth, as they saw it, without being kind of overly combative or rude. They say, "Look, you know, it wasn't intended as a criticism of Christianity, and we weren't saying we're like Jesus or better than Jesus. We were just making an observation about the way society is going, right?"

What terrified them actually was not so much... I'm certainly sure this is true of John... not so much the prospect of a career ending, although that was pretty bad. It was, in a way, something even worse, which was this sense that he would be forced to lie and to sort of not be himself and that they would all kind of have to say, "Oh, yes, you know, we're terribly sorry. We do believe that Christianity is just as, you know, will always survive and be bigger and..." I don't know what whatever the lie would have been that would have satisfied these people, if there was anyone. I think that sense of, like, "We might have to compromise ourselves." And then they pretty quickly work out, "No, we're not going to do that. If we stick together and we talk our way through this and we're just confident, we can get through this." And even if it means hurting our commercial popularity, what's the big deal?

In negotiation terms, they had a BATNA, they had a kind of walk away thing, which was like, you know, "Well, fine, you know, we're just going to carry on making music and enjoying ourselves. And if this is it, we've already done way better than we thought we would do." And so that gave them a kind of fearlessness.

Rock critics and the Beatles’ breakup

Andrew Mitrak: In the late 60s, there's the rise of rock music criticism for the first time. It doesn't seem like rock music criticism was really much of a thing. And Rolling Stone magazine comes out, and John Lennon is the first person on the cover. Do you have any sense of how they approached rock criticism? Or did it actually have any impact on sort of their commercial sales or anything? Or what are your reactions or thoughts on sort of rock criticism at this time?

Ian Leslie: It didn't really have any impact. And as you say, it wasn't really… they sort of created, like so much else, they sort of created the whole category of grown-ups thinking and talking and writing about rock music, right? Their music was way ahead of the… the category of, or the sector of entertainment, music, and wasn't really ready for music of sophistication and depth and complexity. So they were way out ahead of everyone for a long time with a few peers like Bob Dylan and the Beach Boys and The Who. But the charts were mostly full of kind of quite bad sort of pop acts really up until the mid-60s.

So there suddenly starts to become this whole kind of rock critic, rock journalism. And then it does become quite important. It's never really important to them in terms of sales, I don't think. But particularly, it starts to bite around the time that they're splitting up in the wake of The Beatles' breakup, when they're doing solo albums.

The extent to which they really cared about what critics said about their albums is really striking to me looking back on it now. It seems almost unbelievable because, like, McCartney's first solo albums sold really well, pretty well, but he was devastated by the bad reviews. And it really, really hurt him, really got to him. So there was a sense that there was this kind of, like, how am I seen by critics, by my peers? That's really important to me, as well as whether or not people are buying my records. But I think that happens towards the end of the 60s, early 70s, and really the early 70s, maybe through the 70s for a few years, is the heyday of the really, really powerful rock critic establishment.

Andrew Mitrak: I was reading some of the contemporary reviews of Paul's solo work. And I think like I'd brought up Venus and Mars on the in the Rolling Stone review at the time of Venus and Mars. And the opening lines are something to the effect of like, "Gosh, you're really seeing how important John Lennon was." And that it's really missing the presence of Lennon. And it's a Paul review, but the first person mentioned in the review is John Lennon.

It seems like there was this image of John as the tortured artist and the brilliant mind behind the group. And Venus and Mars is an album that I think has aged pretty well overall, and I think a contemporary, like a review today would be different about its assessment of it. I also think Lester Bangs was like a popular critic at the time who'd, you know, called Paul "Muzak" and very, very dismissive of it. And like, they could be really mean about it. So it seems like it's something that, you know, if you're an artist, like, how could you not be impacted by that in some way if something's going to be so vicious about your music?

Ian Leslie: Yeah, and they were very much of their time in that they were mostly male. They responded to Lennon's kind of strong kind of, you know, what we might call kind of like high-agency vibe and his kind of counter-cultural vibe. And, you know, who's making big kind of political gestures around this time in the early 70s. He's part of the kind of anti-Vietnam, anti-Nixon movement. He was on the right side of history, in inverted commas, right? And he was very much part of the kind of counter-cultural movement, which was really where all the kind of hip people were, right?

And McCartney was not really there. I mean, in a sense, he was political. There were certain things that he cared about and campaigned on, like marijuana legalization and vegetarianism. And you arguably had a much greater impact on those causes over time than Lennon did in sort of dabbling with counter-culture for a couple of years. So it wasn't that he was apolitical, and he did make a song about Northern Ireland as well. But it's that he didn't see himself as an essentially political figure in the same way. And he was also just somebody who was unashamedly into being a dad and a loving husband. And that was totally uncool.

It didn't really fit with the kind of prevailing ideas of being a rock star and being a man, you know, being an artistic man and being a genius, you know. You were meant to be conflicted and difficult and weird and messed up and do unconventional things and throw TVs out of windows and and take drugs and maybe be really horrible to women, that's kind of part of it as well. And McCartney was just sort of refusing to do any of that stuff. His reputation took a battering in the 70s, and it got much worse after John's death because John then becomes kind of deified and it takes many years for his [Paul’s] reputation to recover from that.

Apple Corps: A strong brand, but a disastrous business

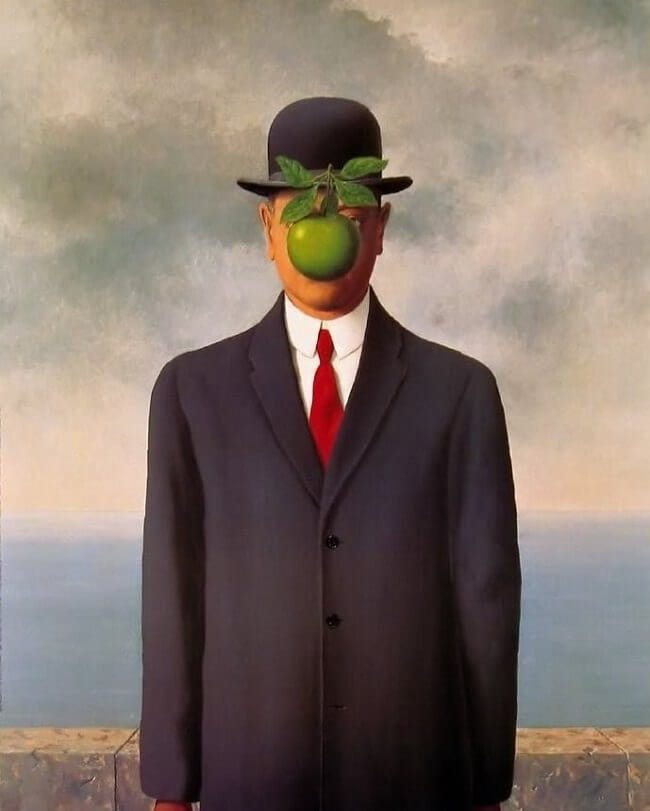

Andrew Mitrak: One other thing I think that's worth highlighting for the marketing element of The Beatles is Apple Corps. And they name their company Apple Corps. We were talking about naming earlier, and you cited Apple as the great computer brand. And it just strikes me that what do they name their company? Apple Corps. And that even though the company wasn't especially successful, that name actually became pretty valuable because of the trademark and licensing and legal settlements with Apple Computer, which they could have never known at the start. But they picked this really great name, and it seems like that seemed to be among the more valuable parts of that company itself. And it seems like it was reflective of some smart branding intuition. Do you have any thoughts on Apple Corps?

Ian Leslie: Well, it was Paul McCartney's name, and he took it from, I think, from a René Magritte painting. You know, McCartney is a huge fan of René Magritte. He just got into him at the time, and you know, there's that famous picture of the man with the apple in front of his face. And I think he took it from that.

He liked the sense of artistic subversion that it was associated with. And they were very much running on instinct through the whole Apple thing. In business terms, that proved to be disastrous because it turns out your artistic instincts aren't that good when it comes to running a business. But in anything to do with the creative side of it, it was they were still pretty good, and yeah, Apple is a great name.

How George Martin is like Eric Schmidt

Andrew Mitrak: Thanks for this conversation, this tour of Beatles history. I know that we've taken a marketing and business approach to this book, but it's... you know, this book is so much more than that. In fact, this business element is just a footnote in the book, and at the core is just this amazing, heartfelt, intimate story of these two geniuses and we were lucky enough that they crossed paths as young men and made all the contributions they made.

But as you reflect on this conversation, are there any reflections on lessons that marketers can draw from The Beatles or other things we didn't talk about when it comes to The Beatles and some of the innovation they did around marketing and branding and promoting their music and their work?

Ian Leslie: I mean, I think there are more. The thing is, like, the more you think about it, the more stuff comes up. One of the things I was thinking about the other day was the analogy between George Martin and Eric Schmidt at Google. You know, when you have a startup and you have these brilliant young guys, and then it's like, "Well, you might need a gray hair, experienced guy." And Eric Schmidt was the perfect guy for the Google co-founders, and he kind of helped. But in other cases, it hasn't worked out because the gray hair thinks he knows better than these kids and tries to impose his experience on them, and it doesn't work.

George Martin was in that Eric Schmidt mode. He used his experience, but he recognized very early on that they were the talent and that they really knew what they were doing, even if they weren't musically educated like he was. They had great musical sophistication and great musical intuition.

So his ability to put his ego to one side and say, "Well, how can I help these guys?" rather than trying to impose my ideas on them, I think is a great lesson there for for startups and and growth.

But yeah, I'm sure we could talk for a lot longer. There's so many lessons.

Subscribe to Ian’s Excellent Newsletter: The Ruffian

Andrew Mitrak: Absolutely. Well, thanks so much for the conversation. As one final question, where can listeners find you online?

Ian Leslie: Well, I think the easiest place to get me is my newsletter, my Substack newsletter, which is called The Ruffian. So if you just Google my name and Substack or The Ruffian, you'll find your way to it.

Andrew Mitrak: Yes, I'm a subscriber to The Ruffian. I love it. It's a really great newsletter that covers a lot on John and Paul and also a lot of other great topics. Ian Leslie, thanks so much for joining me. I really enjoyed the conversation.

Ian Leslie: Thank you, that was brilliant. Thanks a lot, Andrew.