A History of Marketing / Episode 6

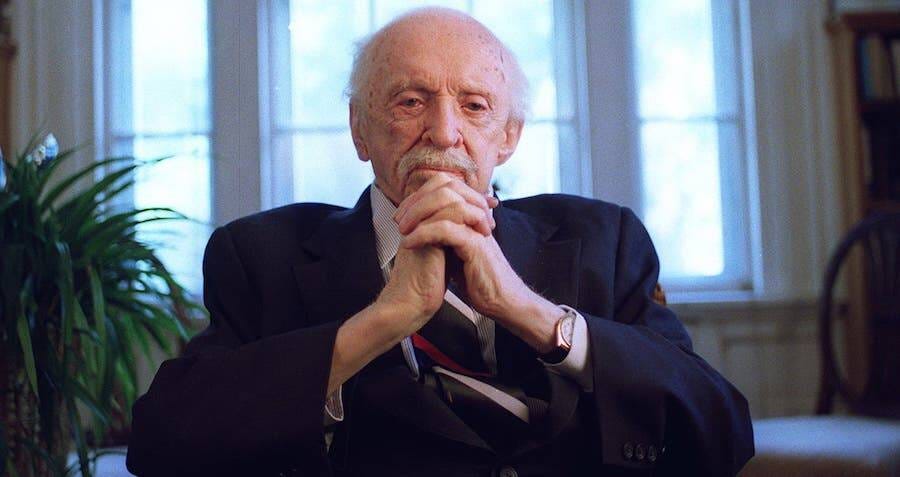

This week we are joined by Shelley Spector, founder and director of the Museum of Public Relations. Shelley's journey into PR history began with an unlikely friendship with the legendary Edward Bernays, the "father of public relations" and nephew of Sigmund Freud.

In our conversation, Shelley shares personal stories of Bernays in his later years, and we use the Museum of Public Relations as a lens to explore PR's early history.

I'm releasing this episode right after last week’s conversation with Larry Tye on the historic life of Eddie Bernays. If you haven't heard that one yet, I suggest listening to that one first, as it will give you richer context for Shelley Spector's personal stories about Eddie Bernays later in his life.

But this conversation isn't just about Bernays. Shelley also highlights the often-overlooked contributions of women to PR, such as Doris Fleischman, Barbara Hunter, Inez Kaiser, and more.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Read the interview transcript, enhanced with links, images, and videos:

Note: This text is from a recorded conversation transcribed with AI. I have read it to check for mistakes, but it is possible that there are errors that I missed.

Andrew Mitrak: Shelley Spector, thanks so much for joining me.

Shelley Spector: Thank you for having me, Andrew.

Edward Bernays and Founding the Museum of Public Relations

Andrew: To start, what inspired you to found a museum dedicated to public relations?

Shelley: It's kind of a long story, but it grew out of our friendship with Eddie Bernays. He lived until 103 and a half, in a mansion outside of Boston, a mile from Harvard. One day, I happened to ask, "What are you going to do with all this stuff when you need to leave?"

He immediately said, "I want to turn it into a museum. I want to turn my house into a museum." He was picturing what Freud's family had done in London. When Freud passed away, his children made his entire house into a Freud Museum. We've been there, and it's wonderful.

I said to Eddie, "I understand where you're coming from, but, no offense, PR is not recognized as broadly as psychology is. Your uncle Freud was a little more famous than you were." He looked really sad when I said this. So I said, "How about we build a museum of public relations in New York?"

He said, "Will you?" And I said, "Yes. It's not going to be an Eddie Bernays Museum; it will be a museum for the whole field."

When Eddie died, the family called us. We came up and walked around from room to room to select those items and papers that we thought were important to have in the museum. We loaded up the truck and drove home, without having a home for the museum yet.

Andrew: We released an episode where I interviewed Larry Tye about his book, The Father of Spin, which was all about Eddie Bernays. For listeners who haven't heard that episode yet, he's just this fascinating person who had all this impact on the world. It sounds like he inspired your Museum. The reason we have bacon for breakfast, bookshelves built into homes, UPS trucks being painted brown, and calling multiple sclerosis "MS"—all these things, including your museum, originate from Eddie Bernays' brain.

You mentioned his being inspired by his uncle, Sigmund Freud. He had a very interesting relationship with Freud, and he was also Freud's nephew in two ways: his mother was Freud's sister, and his father's sister was Freud's wife.

Shelley: Exactly.

Andrew: Can you share more about what inspired him about Freud's museum? Had he visited it before?

Shelley: No, he never went to the museum because he only visited with Freud while Freud was alive. The Freud Museum was built in 1938, after Freud had died. But while Eddie was still a child, his parents would go on vacation in the Austrian Alps. We have pictures of Eddie at age nine with Freud, who had a brown beard, which you don't really get to see.

You can imagine growing up in a household where all they're talking about is Freud and his crazy theories of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis wasn't yet adopted in the US. Eddie and Freud were very close; they wrote letters back and forth. Those letters are now preserved at the Library of Congress.

At some point in the 20s, after World War I, Freud wrote to Eddie, "I need a way to make some money. I don't have any money" because of the hyperinflation. He wanted Eddie to perhaps send him some money. Eddie did manage to send him cigars from Cuba, brought over by another PR pioneer named Carl Byoir.

But Eddie proposed to Freud, "Why don't I get your book, Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis, translated? And have you come over here? We'll do a media tour." It's a classic response from a PR person. It was very much Eddie's work that got Freud to be known as much as he is known now.

So, he had the book translated by a disciple of Freud named A.A. Brill. The book was very popular. Eddie wanted Freud to write byline articles that Eddie would help him write for the popular press, but Freud was saying, "Americans are not going to get it. They're not going to get psychoanalysis. We're talking to an audience of people that are really not that smart and cultured." He really looked down on the US.

Eddie could not get him to come here and sit for interviews with the Times or with Life magazine or Fortune. However, the ideas, because they were so big and relevant at the time, those ideas of Freud spread. And behind the scenes, you have the nephew, always behind the scenes.

Befriending Eddie Bernays: A Personal Connection to PR's Past

Andrew: Eddie is this fascinating character, not just in PR, but in history in general, in the 20th century. You met him and knew him before you founded the museum. What was it like first meeting him? What was his personality? Any stories or anecdotes about meeting Eddie Bernays?

Shelley: You have to remember that during that time—this was the mid-80s—there were trade publications in PR that frequently covered Eddie and his gallivanting around the city with various women. This is how everybody got to know who he was, besides knowing his campaigns. On one side, you had all these campaigns that were being taught in the schools, and on the other side, you had this 90-something-year-old man who was said to be quite an adventurer with women in Cambridge.

The series of events were that I was asked to give a seminar at the Doral Hotel, where there were a bunch of PR seminars being given on that day. One of them, right next door, was Eddie's. He had been giving these seminars called "Two Days with Edward L. Bernays."

After the first day of the seminar, I went, stood outside his class, and I introduced myself. One of the first questions he asked me was, "Do you want to have dinner at the Waldorf?"

Of course, I would love to have dinner, but I also don't want to wind up in the trade publication, being seen by paparazzi.

Andrew: Just to remind, Eddie at this point is probably in his 90s, right?

Shelley: He's 94.

Andrew: 94, wow. Okay.

Shelley: And so I said, "Can I call somebody to join us for dinner?" And he said, "By all means."

The previous Sunday, I was on a bike trip, and I met this guy that I kind of liked. I had his phone number, and I called him from a pay phone. The fellow that I called was a graphic designer, knew nothing about Bernays. I said, "But he's very interesting. He's very historical. He's 94. He's worked with every president of the century. Please come to dinner at the Waldorf."

So he was intrigued. Well, that guy turned out to be my husband and business partner all these years, Barry. Barry just could not—his mouth was agape while listening to Eddie talking about working with Calvin Coolidge's reelection campaign and bringing Al Jolson down to the White House. Stuff that made somebody who didn't know him question, "Is this guy senile?"

Barry and I said, "No, all this stuff is true." And so Barry then said to me, "If this stuff is true, then we've got to go up to his house and do an oral history." So I said, "Yes."

So it all worked out. We went that April to his house and started doing these oral histories. He had never seen a video camera before. We were using VHS—this is antique equipment; it was brand new, but look at it now—and it was really not anything that was sophisticated compared to what we have now.

But it was fascinating. I remember that conversation was about Eddie's role in World War I with the Committee on Public Information and George Creel, and going over and working on the press release for the Treaty of Versailles. You're sitting next to somebody who's talking about something that happened...He wasn't just PR; he was a part of history.

He was a part of history, and he was also an influencer in historical events.

Andrew: Seeing footage of Eddie from this time period is strange because there's a clip of him on the David Letterman show from the mid-80s around this time, and it is this funny, uncanny feeling of almost seeing a time traveler or some sort of anachronism, telling stories from growing up with Freud and his family in pre-World War I, doing PR in World War I, and here he is talking to Letterman, who's still a person who does interviews today. It's just wild, his longevity and how early he got a start in his career and his impact.

I also didn't realize how intertwined your life was with Eddie Bernays. I'd seen, based on some research, that he was a figure that influenced the museum, but not only your marriage and lifelong partner, your dedication to the museum, your career in public relations—all influenced by Eddie Bernays. That's really remarkable.

Shelley: It was very fateful. We found him to be absolutely charming and brilliant. And you're right, it was time travel. To him, he's talking about events in the early 20th century, the teens, pre-World War I and post, and the whole period in the 20s, and he's talking about it like it was yesterday. It was like you and I just talking about maybe the financial crisis of 2008. The memory was spectacular, and he was so charming in the way he told these stories.

So Barry and I ended up going up there three, four times a year until his last birthday at 103. Barry and I always had him sitting in front of the camera or just having the camera roll. Some of the footage that you see in documentaries is from Eddie just sitting at the table with food, not planned with questions. We would just plant the camera on a tripod and capture whatever we would capture.

Andrew: He seems like somebody who kind of had his greatest hits and had his stories and told them so much, he really had them down, just every PR professional should.

Inside the Museum of Public Relations

Now, we could spend hours just talking about Eddie Bernays, but I want to go back to the museum and cover more of it, use that as a lens to cover more of PR history. Just to ground listeners, can you describe what the Museum of Public Relations is in detail? Is it a building they can visit? Is it an online catalog? What exactly is the museum?

Shelley: The museum, from its first day, was online. In fact, it was noted by USA Today to be the first museum to be online, which we had no idea. We just put it online because we knew that people would not necessarily come to see it, but the material we had was so important that we put it online in the 90s.

Andrew: In '97?

Shelley: Yes. So it's pretty old.

So the museum today is in a large space at the PRSA, which is the Public Relations Society of America. They invited us in because we were outgrowing the space we had been in. At some point, we were at Baruch College for four years, and then we had to leave because of renovations they were doing. And so we were at various offices. Then we moved to, which we hope is our forever home, at 120 Wall Street.

We have frequent visits from students, classes, educators, scholars. And it's amazing. At the beginning, most of the people who would contact us would be people who I've heard of or who I know. And now the people really are from all over the world, asking questions about the past and some of the early pioneers.

Andrew: Listeners might also be thinking, what actually is in a museum of public relations? Is it just a big wall of press releases? I know it's not that. (Laughs) Can you describe what makes up the museum and some of your favorite artifacts?

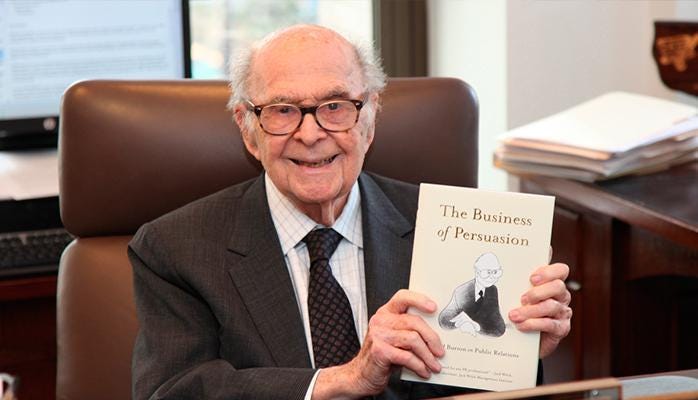

Shelley: When I think about the walls we have and what we've hung up, we only hung up one press release, but it was a very historic press release. It was written in 1952 by Harold Burson about the beginning of the firm Burson-Marsteller, which became the largest firm in the world. Harold Burson himself was a noted pioneer who started, several others, after World War II. They got trained in news writing, etc., during World War II, came out, started working in PR, and then eventually built their own agencies.

So we do have this press release that was written by Harold, and we have the carbon copy of it, which we think is significant because nobody knows what "cc" means anymore. But this was the original press release that Harold typed himself.

Andrew: And just for listeners, also for those who don't know, "carbon copy"—when you see "CC" on an email today, it's "carbon copy." And if I understand, you type something on a sheet of paper, there'd be a sheet behind it, and that would imprint with carbon, and that would be kind of the backup or the additional one, and that would be the “carbon copy” of it, which, 70-plus years later, we still use today in our emails every day. And that's what it is, right?

Shelley: I'm glad you explained that because kids today have no idea. I do ask them about, you know, what is a CC? What is an inbox, for instance?

And so I'll segue over to something else. They have no idea what an inbox is—a physical inbox. They only know the inbox on their email. But we have Eddie's inbox from when he died, and we have in there everything that he had. Because when you used to look at people's physical inboxes, it was papers that were important to them. And he kept the papers that were important to him in this inbox, on his desk. We've since put plastic around them, but I think it's fascinating to look at what he had in there. He had in there articles about himself, yes, but he had a lot of articles about Freud, and he had a lot of articles written about and written by his wife, Doris.

Andrew: It's so fascinating how, when computers developed, they sort of used the analogies of the past, of the physical world. And I think there's a term for it in computer graphic design called skeuomorphism, where you take something from the real world and you put it in the digital... If you see, on my desktop, I still have a trash can, and it looks like a wastebasket. And the "save" might look like a floppy disk, even though floppy disks haven't been used in 30 years or so. And you kind of take things from the past, and you have them preserved in your museum, that are now still part of the digital world. It's just we think about them so differently.

Shelley: You're absolutely right. When kids come to the museum, I go through things —I don't remember the word you just said...

Andrew: Skeuomorphism. (Laughs)

Shelley: ...and show them things that they had no idea existed, Edison's original phonograph, the cylinder phonograph. We have that there. Music didn't always come from a computer; it wasn't always MP3. Sometimes it was a scratchy cylinder.

Ivy Lee: The Other “Father of Public Relations”

Andrew: We've talked about Eddie Bernays. One of the other founding figures of public relations is Ivy Lee. Can you share a little bit about his impact? I'm curious if the museum has any artifacts from Ivy Lee.

Shelley: We have plenty. We have also republished his original official biography from 1966. So we have a biography of Ivy Lee.

He's a fascinating character. Both he and Bernays are noted as fathers of PR, and there are some countries that look at Ivy Lee and not Bernays; there are some countries that look at Bernays and not Ivy Lee.

It was fascinating to study Ivy. He worked with the Rockefellers, and he also represented railroads. He eventually represented the introduction of the IRT subway. Now, imagine, at the beginning, subways were competitive. So one of the things that he did, which was masterful—remember, this is the time of the flu and tuberculosis—so he would put up customer posters where you see advertisements now: "Don't cough too closely," "Don't sit too closely," "Wear a mask." It was the first customer communications of its kind.

But more importantly, he was counseling the Pennsylvania Railroad. One day, they had a derailment around Atlantic City. You can see pictures of this, with cars literally hanging off of this bridge, and people were jumping out of the windows.

So the CEO of Penn Railroad said to Ivy Lee, "You've got to keep this quiet." Because that's what was done during the day, during the Gilded Age. Vanderbilt said, "The public means nothing," right? "The public be damned" is what Vanderbilt said. And the CEOs of the time would disregard what the public would think. "The best thing is, they're too dumb to understand it anyway. Don't let them know."

Ivy Lee said, "You cannot do that. The press is going to find out about it eventually. If you don't talk to them, they're going to write a very negative story." So he wrote the first—what was not yet called a press release—it was called a "Statement from the Road," about what had just happened.

He wanted to get the company's position out there. He wanted to look open. That was a very important concept back then; people just hid the news. But Ivy Lee said the best way for you to come off looking trustworthy, as a company that deals with your customers all the time, is to take preemptive action. And this became a founding principle of crisis communications.

Andrew: There are so many firsts to unpack in that story: the first example of crisis communications, the first press release itself. Folks who aren't intimately familiar with PR might think of PR as, "They're just spinning things on behalf of companies. They're just trying to tell the best version of the story." And, of course, to some extent, you have to represent your clients in the best way possible. But also, this is a founding example of, "No, compared to what was before, this is actually a lot better." Before, they'd sweep it under the rug, try to hide an awful tragedy with a train derailment, and instead, they're bringing it to light. They're kind of understanding that this is a new age in communication, and you need to not sweep it under the rug but actually tell people about it.

Shelley: Exactly. You've got to preempt the reporter. So the reporters are taking the information from your release, and they're going and interviewing the CEOs. And Ivy probably trained them beforehand to be honest and forthcoming. So it was a whole different way of looking at the relationship of what was then known as a publicist with the press.

Doris Fleischman Bernays: The Unsung Partner in PR's Early Evolution

Andrew: I want to move on to somebody you brought up briefly, which is Doris Fleischman Bernays. You mentioned that when you looked at Eddie's inbox, he had letters and communications from Doris, who had passed away 15 years or so before Eddie. So he preserved these for years. And Doris was not just Eddie's wife; she was also a really important contributor to PR in her own right. I understand she was sort of more behind the scenes than Eddie, but they were equal partners. Can you describe more about who Doris was and what her contributions to PR were?

Shelley: I'm very sorry I never got to meet Doris. And I think that PR history would be very different if Doris were able to be more visible at the time. She was not the first professional public relations person who was a woman—it was actually a woman two years before, who we only just discovered; her name was Zelda Popkin.

And there were probably many others in the teens. But she did some very sophisticated work and writing. She was a tremendously good writer. She had ideas, but back then, women were not allowed to share those ideas. If Eddie had clients in the room, the only woman allowed in that meeting would be a stenographer.

Doris stayed away from the main stage; she was behind the scenes. Now, a lot of people have asked me, did she have any impact on his big campaigns? I don't know. I have asked the family about this, and they say no. I've asked Bernays about this, but I think that for two of the campaigns, he had to have been influenced by her, even if it wasn't so obvious.

So Doris was part of the Lucy Stone Society, which are a group of feminists of the time, suffragettes, former suffragettes, who believed that women should be independent and use their maiden names. Which is something that is a legendary story—that she insisted on keeping her maiden name on her passport.

And on the first night after they got married, on their honeymoon, which started out at the Waldorf, here she is signing in as Doris Fleischman, with a fellow named Edward Bernays, and it doesn't look very kosher to these people in 1919.

Andrew: And you mentioned her passport—she was the first married woman to have her maiden name on her passport in the US, right?

Shelley: That’s right.

Andrew: It's a lot of firsts in this group.

Shelley: And Eddie instinctively knew that that would make news. As much as Doris herself really wanted to do this, Eddie also knew that that would be news-making. But he wouldn't send out a press release about it; he would just let the press find out themselves.

So that the press feels that they were uncovering a piece of news.

Andrew: And I think you were stating that there were certain major campaigns that she may have influenced behind the scenes. And, of course, there's the Torches of Freedom campaign.

Shelley: That's the one.

Andrew: That's the one that very prominently used women and turned lighting a cigarette into a statement about women's empowerment. Do you think she was sort of behind the scenes in that one, potentially?

Shelley: Yes, I do. I have felt, even if she didn't work on the campaign directly, just who she was—she was a liberated woman. She smoked very heavily. And I guess when she smoked, she felt liberated. Now, at the time, it wasn't about making more women into smokers. Women were not allowed to smoke in certain theaters and restaurants, concert halls, all over the country. That's a crazy thing, that there would be signs and posters inside restaurants: "Women cannot smoke here." That's nuts.

And so it was encroaching on women's freedom. And so that's why there was an appetite at that time for the Torches of Freedom, part of the Easter Parade. And it wasn't just these women in a separate parade; it was part of the Easter Parade, where everybody's already dressed up. And there's some marvelous pictures of debutantes and these men, these high-class men wearing these top hats, walking in the Easter Parade.

But the brilliance of Eddie was that, again, he didn't announce it. He didn't send out a media alert and say, "If you get to the parade in time, you're going to see these women with cigarettes out in the open." That didn't happen. He knew that there would be photographers there shooting the Easter Parade, but when they started seeing women smoking out in the open, in public, that made news. But nobody knew who was behind it.

Andrew: So he was kind of a magician in the background.

Shelley: Absolutely.

Andrew: That sense of showmanship and how to create a spectacle and a scene. And you suspect that... Doris was an equal partner at his firm, she was a smoker herself, they used the guise of women's liberation to break barriers, let them smoke more, and, of course, if they can smoke in more places, they can smoke more products for their client, Lucky Strike or American Tobacco. So it all kind of came together that way.

Researching Doris, I saw she edited and published a book in 1928 called An Outline of Careers for Women: A Practical Guide to Achievement. And this, in itself, just that she edited and published a book all about women's careers, says a lot about her. And in it... It's all available online at this point; I think it must be in the public domain or something. And in it, she wrote a chapter herself on public relations. And I want to just quote the introduction:

"The profession of counsel on public relations is so new that all who are engaged in it, men as well as women, are pioneers. No traditions have grown against women's participation in it, and women will share the responsibility of developing and shaping this new profession. It is so new that its ultimate possibilities for women lie in the future."

I just think this is so prescient, that now PR today, I think, has—depending on what you read—it's 65 or 75% women who are in it and who lead it. Do you have a reaction to this quote? What's your take on it?

Shelley: It's very prescient. I wish that Doris was alive in the 80s, 90s, to see women rising to the top of agencies. Because back then, she's talking about women who are doing the work of PR. She's not talking about women who are leaders of PR agencies. In her mind, she could not imagine how big agencies would be one day and how women would have a role in those agencies, and running those agencies, being CEOs. She could not imagine this because it was unheard of, just unheard of.

But she was offering up her own experience as a public relations counselor. Now, one of the important things here is that it was Bernays and his wife who came up with the phrase "counsel on public relations." Before then, it was just "publicity."

When Ivy Lee would just call it "publicity"—even though he could be talking about crisis management—"publicity" did not become a kind of low-class word until much later. But "counsel on public relations" sounded like a lawyer.

Andrew: Exactly.

Shelley: So, but she was pretty much saying, women can and should be part of this growing profession. But back then, there were no professional women. And the only professional woman that I know of during that very time, in the 20s, was a woman named Belle Moskowitz, who was a political consultant to Al Smith when he was running for presidency. And you can see in some of the old documentaries of Al Smith, there is Belle, a rather big woman with a hat and a feather in it.

But yeah, it's really something that she would be so prescient, and she would be such a fan of women. And she wrote a book—I don't know if you've researched this—called A Wife Is Many Women, which says it all. A wife is a mother, a wife entertains in the home, a wife is a wife to her husband. We play so many roles. And this all came out, I think, in the 80s, when women—they were called "super moms"— when there was a front page of Newsweek with a working mom carrying a briefcase on one hand, in her business suit, and her baby on the other hand. That's what Doris was envisioning.

Of course, Doris had the means to hire a lot of help raising her children. Most people don't. And we still have to juggle, as women, we still have to juggle, but we're doing it.

Barbara Hunter and the Fight for Female Leadership in PR

Andrew: So Doris Fleischman was the first woman to be a 50/50 partner at a firm, and I want to also ask you about Barbara Hunter, the first woman to own and lead a major PR firm. And before I ask, I also want to acknowledge an unfortunate coincidence in timing. We're recording this in December of 2024, and just yesterday, we learned the sad news that Barbara Hunter passed away at the age of 97. And in her obituary, the last line reads,

"Donations and tributes in Mrs. Hunter's name could be made to the PRSA Foundation or to the Museum of Public Relations."

First, amazing that Barbara Hunter had such a close relationship with you and the Museum of Public Relations; clearly, it meant a lot to her. And if you're able to, just share who Barbara was, what impact she had on the industry, and what your relationship was personally with Barbara Hunter.

Shelley: Well, yes, I'll take the last question first. She was very active. She sold the agency, Hunter PR, which she created after working at another agency called Dudley-Anderson-Yutzy, and she had sold that off and created Hunter PR.

So the founder of Hunter PR—or the person she passed the torch to—is named Grace Leong, current CEO, marvelous CEO. And we had worked with Grace for years—"Let's get Barbara on the panel," because... There were a few women who are of an age where, you know, you want to get them while they're still very sharp. Barbara continued to be sharp until the very last day. Amazing.

But she would tell stories about what it was like to work in a very anti-feminist world. The business world was... If you look at Mad Men, that's what the world was.

Even though Mad Men was set in an advertising agency, it's the same kind of interactions between men and women, and how men saw women, and what was allowed in the office, right? So despite all that, Barbara Hunter and her sister, Jean Schoonover, managed to work with the respect of men and actually bought an agency, renamed it Hunter PR, and managed a thriving business—thriving. It's amazing.

Andrew: Yeah. Well, you mentioned how Barbara was sharp right up to the end. I listened to an interview that must have been recorded within the last year or so, where she tells this story. And she tells the story of how she and her sister bought the PR firm that was then known as D-A-Y, right? And the amount of sexism they were up against was just shocking to listen to. Of course, you've seen it portrayed in things Mad Men, but hearing it firsthand from somebody...

And she said that when she bought this firm that she had been working at, and she purchased it, the men who worked at the firm, they all left. They didn't want to work for a woman. They took their clients with them. And then sometimes they'd get meetings with clients, but they just wanted to listen to them almost as a novelty, where they just said, " We just wanted to say we listened to the first women-led PR firm pitch." And they didn't really give them serious consideration, which just seems so rude and a waste of time.

What she was up against then, it's kind of gross to hear about. It makes you sad. But then seeing what she kind of overcame and what she accomplished and what she built it into is so remarkable.

Shelley: I think we have people like Barbara to thank for the industry allowing women to do the same job as men and for allowing them to rise to the heights, as far as they can go. As you mentioned, it transformed sometime in the 80s and 90s to a dominantly woman field. But, unfortunately, the top of the industry are all men, still—the CEOs of the holding companies who have bought a lot of the agencies.

But Barbara was out there. She just didn't give a damn. If she had the best idea, that's the... If you look at all her ideas, they came up from her brain. During agency selections for new clients, you'd have to come up with a unique idea. And it wasn't good if the client prospect would hear an idea and then go to another agency. I'm sure that did happen. But with her, they came up with brilliant ideas, mostly about food. She introduced the idea of food product PR.

And some of those products... Tabasco was with the agency—currently with the agency. And the last time I saw Barbara, on Founders Day, I got a whole souvenir bag of different kinds of Tabasco, which I still have. But yeah, it forced them to come up with unusual ideas and not just the standard way of doing things. I think it made women work harder and stand out and realize the value of big ideas. When I came into the business, there were no women professionals. I didn't know how to even find them.

Andrew: Wow.

Shelley: Because we didn't have an internet back then. So I'd see an occasional woman at an industry conference or a lunch, but usually, I was the only woman in the room. Like Peggy…

Andrew: Like Peggy in Mad Men. Right.

Did Barbara Hunter... Did she run her firm differently than other firms of the day? Did she lean into the fact that it was woman-led and as a sort of competitive advantage, or attracting brands that marketed to women as their clients? What was her approach to that?

Shelley: Well, considering that she was handling food PR, she knew the consumer much better than the men did.

And that was really what set her apart. That was her USP. She was... It wasn't like she was running oil... She was handling oil and gas companies or electric utilities or steamship firms. She really knew the consumer, because she was a woman herself. She was a mother. She ran a house, so she got it. And it was very smart for them to pick this category of client—of food—that they knew much better than the men did. It wasn't until years later that women started handling things that were not fashion and all this kind of stuff, which I personally hated, which is why I went into a niche part of PR, in financial PR, because there weren't many women doing it. And that, to me, was a very serious subfield of public relations—the financial services industry.

Inez Kaiser: Breaking Barriers in Public Relations

Andrew: There are a lot of women to cover in the history of PR that are leaders, but one that I wanted to specifically highlight was Inez Kaiser. Can you share the story of Inez Kaiser with listeners?

Shelley: Let me, just take a step back, because I think this is an interesting story. We had, as I mentioned before, we had the whole museum set up on the library floor of Baruch College and hosted a lot of student classes. And so one of the classes comes in one day, and they're a diverse class, and one of the young women was walking around and looking at the exhibits and shaking her head. And usually, people like this stuff; I didn't understand why she didn't like it. And she sat down and raised her hand, and she says, "How come no one here looks like me?"

And so this was October of 2016, and I was just dumbstruck because she brought up such an important point, and I didn't know what to tell her exactly then, except that I was going to fix it. And I told her and the whole class... I made a promise to her class and the professor: we were going to change things. So from October to Black History Month, February of 2017, we started researching Black and other people of color and their role in public relations history. So that now, half of the museum is about diverse people in PR history, because that is one way to bring more diverse people into the industry.

So Inez is one of those people. But she was the first woman, as far as we know, the first Black woman to open a PR firm. Now, it wasn't she opened it in New York or LA; she opened it in Kansas City, Kansas, where it was tough to be a woman, and it was tough to be a Black person. But one day, she decides she needs her own office to open up this firm, and none of the landlords of commercial property in downtown Kansas City wanted to rent to her, not only because she was Black, but because she was a woman.

And so she said, "I'll tell you who's going to be interested in this story: ABC, CBS, and NBC. And if you want, I can go give them a call later this afternoon." Next thing she knows, all the brokers are coming in, giving her tours of various offices in downtown. To her, it made no difference if she was a woman or she was Black. "Give me an office."

And this is during the Jim Crow era, 1957. That's what's most spectacular about this story, is that she just didn't care. She just didn't care. But for consumer product companies, she was a great bridge to the newly affluent post-war country, and the affluence also was part of the Black communities around the country. So they took advantage of that. Various consumer brands hired her to find a way to communicate with them, and she did that. She was also a Republican and worked for the Reagan administration as far as promoting the idea of Black people starting up their businesses, and this became part of the Small Business Administration.

So the day I found out about her, somebody had called me, was writing a paper about her, wanted to know if she was still alive. I had no idea; I never heard of her.

So a person in my office decided to Google her and found out that her son, Rick Kaiser, was living—and living in Kansas City. And so she just picked up the phone and called him.

And she says, "How is your mother doing?" And he said, "Mama is doing just great. She's in the next town over, in the assisted living place, and she's 96. And would you like to talk to her?" And we said, "Are you kidding?" And so we have this two-hour phone interview with her that's on our website that, to my knowledge, is the only recording of her telling her life story.

Andrew: Wow, it's amazing that you have that oral history from Inez. It seems like a treasure. I think that that kind of work is exactly what's inspiring me to do this podcast as well... so many marketers don't know the history of marketing. I myself am still just learning, at the beginning of this journey, and I think it's such cool work to capture voices, capture these stories, so they're not lost to history, and that listeners can find them, and that those who are curious can learn about this.

Supporting The Museum of Public Relations

I've just really enjoyed this conversation, Shelley. How can listeners support the museum, follow it online? Where would you point them to?

Shelley: I would say go to PRMuseum.org. There's a donation page there, there's listings of our events that are coming up, or events we've done in the past. We've done 37 events, programs, panels, mostly regarding DEI and history, and there's a lot of videotape up there, and oral histories. And I encourage everybody, whether you're a student or not a student, or whether you're a PR person or not a PR person, it's interesting in history regardless.

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely. Well, I'll post a link to that in the show notes with this podcast. So, Shelley, thanks so much for your time. I really enjoyed the conversation.

Shelley: Thank you, Andrew.