A History of Marketing / Episode 25

I wanted to do something special for the 25th episode of "A History of Marketing." While I love the conversational format of the podcast, I stumbled upon a story so incredible, so important, that it demanded a different approach. This story is told in a documentary format that took 10X the usual effort to produce.

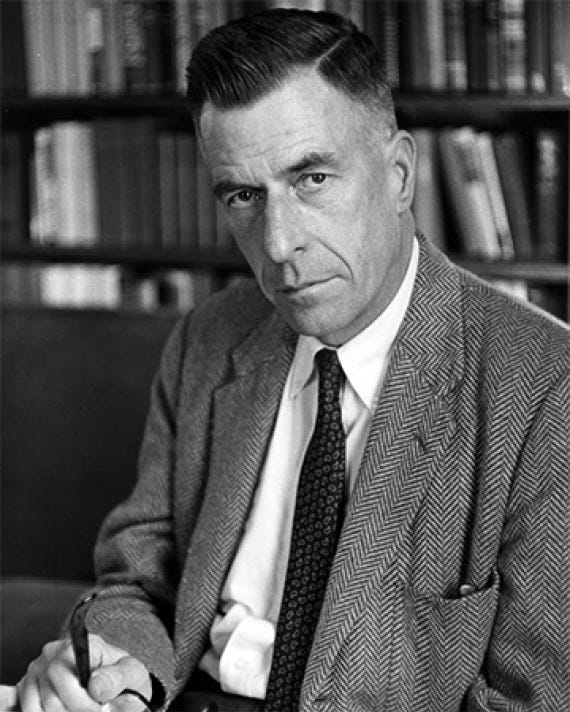

That story belongs to Wroe Alderson.

Ever heard of him? I hadn't either until I started this podcast. Yet, his short Wikipedia page calls him "the most important marketing theorist of the twentieth century and the 'father of modern marketing.'" (A title usually bestowed upon Philip Kotler.)

How could such a pivotal figure be almost completely unknown today?

Answering that question took me on a six-month journey. What I discovered was a life that reads like a great American novel. Before he was a marketing theorist academic, Wroe Alderson was a hobo riding the rails, a prizefighter, a lumberjack, a poet, and an FBI suspect who traveled to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

To do Wroe’s story justice, I decided to break from the usual format. In this episode, I weave together multiple interviews—with Ben Wooliscroft, a professor who has spent his career studying Alderson and chronicled his life; Stan Shapiro, a 91-year-old colleague who co-authored a book with him; and with his only son, Evan Alderson, who shares powerful stories about the defining moments of Wroe Alderson’s life.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

This episode pieces together stories from the astonishing life, the groundbreaking work, and the mysterious disappearance of the most important marketing figure you've never heard of.

You can listen to the audio, and I’ve included images and footage in the video version and the transcript below.

I hope you find Wroe Alderson as inspiring as I do, and that this episode can play a small part in bringing renewed interest to Alderson’s life and work. If you like this podcast, please consider sharing it with a friend or posting about it on your preferred social network. As always, you can email me at hello@marketinghistory.org.

Episode transcript:

Andrew Mitrak: My guess is you haven't heard the name “Wroe Alderson” before. I hadn't heard of him either before I started this podcast series. The Wikipedia entry on Wroe Alderson is less than 500 words long. Here’s the first sentence of it:

Wroe Alderson, 1898 to 1965, an active Quaker, is widely recognized as the most important marketing theorist of the 20th century and "the father of modern marketing."

That's quite an introduction. So, how is it that I know nothing about him?

Ben Wooliscroft: If you're a physicist and you'd never heard of Newton or Einstein, that's where we are in marketing.

Andrew Mitrak: This is Ben Wooliscroft. He's a professor at Auckland University of Technology and co-editor-in-chief of the Journal of Macromarketing.

Ben Wooliscroft: How did this discipline join together around the central character who was president of the American Marketing Association, who created the Marketing Science Institute, who was heavily involved in starting the Management Science Institute, incredibly influential, and yet he died and very quickly his theories almost evaporated.

Andrew Mitrak: Could this really be true? How could one of the most important figures in marketing theory be wiped from the pages of history? To my knowledge, there are no videos of Wroe Alderson, there's no audio of him speaking. I couldn't find a single podcast episode about him. The only YouTube video about him is from some spam account that scrapes Wikipedia pages and reads them in a robotic voice.

Robotic Voice: “He founded Alderson & Associates and served as a professor at Wharton University of Pennsylvania after joining it in 1959.”

Andrew Mitrak: It has more than 93,000 uploads to date…. But after scouring the internet, I found a massive 572 page volume called, A 21st Century Guide to Aldersonian Marketing Thought, published in 2006. Within this tome, there's a 30 page biography written by Ben Wooliscroft.

Ben Wooliscroft: Thank you for inviting me to come and talk about Wroe Alderson who's been the basis of much of my career. To work out why we lost the theories, I wanted to talk to as many people who were alive who had been there and seen that transition. I sat down and tried to put the narrative around his life, because he was a fascinating character.

Andrew Mitrak: Wroe Alderson's life is an incredible story. Here's a teaser. At various times, Wroe Alderson was a hobo, a lumberjack, a teacher, a prizefighter, a soldier, a football player, an academic, a government policy maker, an entrepreneur, a poet, a Quaker, an FBI suspect, and more. Reading it feels like a character that was part Twain, part Hemingway, part something else.

1898 - 1915: Born into poverty in rural Missouri

Andrew Mitrak: I believe the clues to understanding Wroe Alderson's approach to marketing are in his life story. It starts with his birth back in 1898 in rural Missouri.

Ben Wooliscroft: They were a poor family, a lot of children, mother, father.

Evan Alderson: He had lots of brothers and sisters. Family of seven kids, I think.

Andrew Mitrak: This is Wroe Alderson's only son, Evan Alderson. He's a retired professor from Simon Fraser University.

Evan Alderson: His mother got a degree at a teacher's college, which was unusual at that time for a woman to receive an actual degree at the teacher's college. She was a very sweet woman. I think she was probably part of his intellectual development in some ways or his curiosity about the world and so forth.

Andrew Mitrak: If it's okay, I'm just going to read a little excerpt.

Evan Alderson: Absolutely.

Andrew Mitrak: “Wroe Alderson graduated eighth grade and left school at the age of 15. As a young man, he left home in Missouri and took to the rails, living as a hobo and traveling as far as Washington State. Pre-World War I, he held many manual and menial jobs including at a tannery. While he traveled around the country working, he would send money to support the family each month... Alderson was an able fighter and was involved in a number of prize fights.”

I'm going to stop. I could go on, but when I hear that, I'm like, “What?!”

Evan Alderson: (Laughs)

Andrew Mitrak: This is the person who became a renowned academic and scholar and father of marketing thought? Each paragraph - each sentence really - felt like that could be an entire chapter of a book.

Evan Alderson: Let me just say something about the record that you have from Ben Wooliscroft. I think that a lot of the facts even in that story that you just read me are maybe not quite accurate. There are a lot of memories at play. For example, about his education. Actually, Wroe graduated high school at the age of 16.

I'm not entirely sure that that's different from completing grade eight because I don't know what the educational system was at that time.

The other thing that I remember from a story that I think is very important that really hasn't come out in much of the writing, he talked a lot about his father being a very strong guy. There's this fable that he actually lifted huge weights and so on at fairs and even like train assemblies and stuff and which again may be fictional or maybe not, but he was a spectacularly strong guy. And I think that was a big influence on my dad.

He left home at 16, my dad. And I suspect that before he left home, there were various sessions behind the woodshed or in the barn or either whipping or by hand, he got beaten. And I think that made an impression on him. And I think he left home for a reason.

I think in some ways, I think he lit out for the territories to paraphrase Mark Twain, right? That he wanted to get away from home.

The one story he told me that I can remember that I think is very informative, and he told me he was quite sentimental about it. He was on a train somewhere. I don't know quite where. I know he tried to sign up for the army early.

He told me this story of being on a train with some other young men, and looking out the window, and unexpectedly seeing his dad outside the train, waving. Waving at the car in front of him, and then he went by, waving at the car that he was in, and then continuing to wave. And he realized that his dad wanted to know that he cared for him, and that he was wishing him well, and that he was going to stand there for a long time, continuing waving in hope that his son would see him.

That was his interpretation, and I think it was a very moving moment for my dad about his dad. After years, it's still a moving moment for me.

1910S: WWI, Spanish Flu, and family tragedy

Ben Wooliscroft: He spent some time in the army, but it was interesting talking to people. They talked about him as being severely left-handed. And there are a lot of left-handed people out there who can still use a rifle in a right-handed way. And the First World War was not an inclusive war. Here's your piece of equipment. You will use a bolt action rifle. If you cannot manage that with your right arm in the standard model, you're not much use to us. And he really struggled. So, he ended up working as a typist in the army during the First World War.

Andrew Mitrak (Speaking to Evan): When Wroe was enlisted in the army, what was called the Spanish flu broke out and this had a terrible impact and a terrible tragedy that struck Wroe's family and your family. This is your grandfather who passed away and your aunt and uncle, Wroe's brother and sister, passed away during this 1918 flu pandemic. A really horrible tragedy that leaves some lasting trauma. Did he ever speak to that experience?

Evan Alderson: I do think he was probably very supportive of the family after his father died. He did, I think, support them financially in various ways and helped them out. So, I think he continued to be attached to that side of his family.

Andrew Mitrak: Do you think coming back to this train moment, as he's departing the station, do you think that was the last time he saw his father?

Evan Alderson: It's possible. It's possible that it was. Yes.

Ben Wooliscroft: Now, of course, after the First World War, there were really tough times. So, we've got this man who has been brought up in what we would consider now abject poverty, desperately seeking work, looking for income to send home to keep the family.

Early 1920s in Washington State: From lumberjack to Renaissance man

Evan Alderson: As we know, he was stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington State. I think that's where he was a lumberjack actually. He was in the West Coast forest. He sought out an education, and while he was in Washington, he ran across this very interesting economics professor.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, Selden Smyser.

Evan Alderson: Selden Smyser, which I don't know anything about, except that my dad admired him and got very interested in economics as a result of that, and was encouraged to go off to study.

Ben Wooliscroft: And really encouraged him to come to university where Wroe started his first degree, and you've dug up some amazing stuff from Central Washington University.

Andrew Mitrak: Let me jump in and explain this. So, Wroe Alderson was enrolled in what was called Washington State Normal School. I had never heard about normal school before, but this was the historical term for a teacher training institution.

Washington State Normal School is now known as Central Washington University, which is about two hours east of where I live in Seattle. I looked up Central Washington University's archives for 1922 and 1923, the years that Wroe Alderson attended. I found digitized copies of their yearbook and newspaper clippings. And Wroe Alderson was all over them. He was president of the student body, an editor on the student newspaper, a property manager and actor in the drama department, a fraternity member, and a tackle for the football team, which won a regional championship.

This was new information to Wooliscroft. It wasn't in his biography, likely because Wooliscroft wrote it 20 years ago before these documents were digitized and made available online.

Ben Wooliscroft: That's really amazing to see the photos you've sent through of him in his football garb. It's a shame there isn't a tape measure beside him because by all accounts, he was around 5'2", 5'3".

Evan Alderson: He was pleased with himself about his football because he, shorter and smaller but equally strong as the big guys on the team.

Ben Wooliscroft: And also how broad his contributions were being involved in theater, looking after the magazine for the year, and really a renaissance man, one might say.

Mid 1920s: Washington D.C. and the US Department of Commerce

Evan Alderson: That's what he really wanted to do, was to get a real good education in economics and go that direction.

Ben Wooliscroft: Interesting to go from Washington State to Washington D.C., finishes his degree at George Washington University. There's a real theme running through here.

Andrew Mitrak: For listeners who are outside of the United States, I'm sure all the Washingtons are somewhat confusing. But he's moved from Washington State to Washington D.C., which is about as far within the continental US that you can go. It's a very big trip. He's in Washington D.C. He earned his degree in economics and statistics.

Ben Wooliscroft: And then to employment for the US government looking at supply chains. That was foundational to I think everything that followed was his really rich understanding of how goods were distributed through the American economy. And that was a major topic for marketing at that time because it was a real challenge and efficiency was not primary.

Andrew Mitrak: This is the first moment within the story where I start to see the trend line into being a marketing theorist. And as you mentioned, it's supply chains, it's analyzing efficiency of drugstore purchasing policies, and what were the major contributions of Wroe Alderson's early work at the Department of Commerce?

Ben Wooliscroft: This was not a prosperous time for America. We've got the Great Depression, and he's going around and there are a whole lot of people who are running drugstores and they've got reps coming to see them and saying, can I sell you some drugs? Can I sell you some goods? Now the drugstore owner knows the people who are coming to see me are on commission. If I don't buy something, that's someone who doesn't eat tonight or whose family suffers.

The phenomenon that occurred was a whole lot of drugstores would have five or six different brands of aspirin on their shelves. They'd buy a small bit from everybody because they felt this social responsibility to their fellow man, usually a man on the road as a sales rep. Lots of small purchases, very inefficient supply chains, lots of little deliveries coming through, but a very human world view.

The first marketing question: “How do we get goods to market?”

Andrew Mitrak: Later, we hear about things like the 4 Ps, product price place and promotion, and so much of marketing today, we think of the promotion part of it, but that place part was more the distribution part, the logistics part, the supply chain and where somebody chooses to expand. And it sounds like this is more sort of the area that he's studying.

Ben Wooliscroft: Yes, and the first marketing question was really, how do we get goods to market? Some of the early definitions of marketing explicitly excluded sales. They weren't interested in promotion. They were only interested in how do we get goods to the retailer? After that, it's nothing to do with us. That's a different discipline.

Marriage to Elsie Star Wright

Andrew Mitrak: He was an incredibly hard worker at the Department of Commerce and one illustration of this is that he meets Elsie Star Wright, who becomes his wife, and this is so funny. He gets married on Christmas day, not because he wants to get married on Christmas day, but it's the only day he was sure he could take off work.

Ben Wooliscroft: Certainly she was an intelligent person, a very caring and moral person. They clearly cared for each other, they had a good relationship. Elsie was doing her PhD. A number of times when she was getting close to finishing her PhD, something would come up and disrupt it.

Evan Alderson: She graduated in Sciences and she went into embryology and was working on her dissertation for a long time to get that done and kept having kids instead of completing it. She would call me her little PhD because after she had me, she gave up on trying to… having three young kids to take care of, she gave up on trying to complete it. She lived a very domestic life after she was married, but she was a very intelligent and skilled person, and had her own serious intellectual capacities.

1940: Conversion to Quakerism

Andrew Mitrak: Yet another curveball in his life story is he became a Quaker. I looked this up in the 1930s and 1940s, they accounted for less than one in 1,000 Americans.

Evan Alderson: I don't know how much you know about Quakerism, but it's had its own very sectarian moments when William Penn was off getting his colony and George Fox was refusing to take off his hat to the king and that kind of stuff because every person, every human soul was equal. And as the Quaker saying was there is that of God in every man and that whole notion of a kind of fundamental human equality. They had particular manners that they preserved over time, like we had a somebody in our community who never wore buttons because they were frivolous, so he had to have shirts that were pinned together in some ways and all that kind of stuff of not false showing of yourself and so on. Both had some religious backgrounds, but I think they found a home there.

How the Quakers helped standardize fixed retail pricing

Evan Alderson: The other thing that was, I think, influential for him is that Quakers were very adamant about single pricing. That is to say, you didn't barter.

Ben Wooliscroft: If you go to a Quaker shop and ask them what the price is, they tell you what the price is. In the English language world, Quakers and other sects that are extreme truth-telling, created the fixed price. Otherwise, at that time, if you went to a shop to buy something, it was a skilled activity. You had to be ready to negotiate the price of something. As soon as we get a Quaker shop, the price is the price. This is a major breakthrough in commerce and in the retail environment.

Andrew Mitrak: I'm by no means an expert on Quakerism, but I understand they value equality, they value simplicity and community, reverence for nature, and if you look at his writings about things being interconnected, that marketing isn't purely about squashing your competitor, but there's a lot of opportunity for coexistence between companies that it seems like there is a thread between how Quakerism influenced some of Wroe's philosophy when it came to marketing.

Ben Wooliscroft: Yes, and one of my favorite after dinner stories is Wroe Alderson sitting in a Quaker meeting. And the legend which I have heard from multiple sources is that it came to him as he was sitting there waiting for inspiration from God, that God was looking for humans and humans were looking for God. In the same way that consumers are looking for suppliers and suppliers are looking for consumers. And this idea of “double search” came to him.

Inspired by his religious devotion and meditations, a different view of the world from what was predominantly a supplier sends goods into the world to a more negotiated market where there's a recognition of search on both sides, a much richer and systems oriented marketing view.

1943: World War II and the Office of Price Administration (OPA)

Andrew Mitrak: Wroe Alderson converted to Quakerism in 1940, and then World War II breaks out. His family takes in refugees from Austria and Germany and this just speaks to their ethics and maybe their Quaker philosophy, that's that in action. It's a really admirable thing for them to do. And then he also joins the Office of Price Administration and he works for the government again. Do we have any record of what his work was at the Office of Price Administration or what did the Office of Price Administration actually do?

Ben Wooliscroft: The Office of Price Administration was responsible for stopping rampant inflation which is typical of war, followed by a great depression.

If we look at the history of modern warfare, we see almost without exception, some depression cycle follows a major war and that we have rampant inflation with the reduced supply during the war. So, the Office of Price Administration was charged with avoiding that situation and they did that through a number of ways: rationing, which visited the US for a short time, clearly kept going a lot longer in other countries. But then they added the marketing side and a lot of social messaging around not paying above the ceiling price.

[Archival Government Video] OPA Narrator: Here is the OPA meat regulation. OPA requires tray posting of every display with grade, points, and price. 85 cents is illegally high for any cut. In addition to tray posting, OPA requires the butcher to post a list of ceiling prices and the points required. You can help to hold the home front line against ruinous inflation if… You know your meat!

John Kenneth Galbraith and “Countervailing Power”

Ben Wooliscroft: They had a really strong campaign against black marketeers and that the selling price, you would be supplied. This is why I visited J.K. Galbraith, the smartest individual I've ever seen, because he was the head of the Office of Price Administration.

Andrew Mitrak: It's worth a slight detour to talk about John Kenneth Galbraith. Galbraith was a Canadian-American economist who served in the presidential administrations of Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson. He received both the World War II Medal of Freedom and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and he was appointed to the Order of Canada. He published four dozen books and several of them were best sellers.

(An amazing side note: Galbraith also popularized the term “conventional wisdom”)

In 1952, Galbraith published his book, American Capitalism, The Concept of Countervailing Power. Countervailing power is a concept kind of like checks and balances, where the power of large corporations is held in check by the strength of other groups like labor unions and organized retail buyers.

Evan Alderson: Countervailing power. That's a term that Kenneth Galbraith used. My dad said on several occasions, he thought Kenneth Galbraith had stolen that term from him. Maybe not the term, but the concept from him.

Ben Wooliscroft: Wroe was definitely involved in that sort of supply, messaging around it. J. K. Galbraith didn't recognize [Wroe Alderson’s] name. I'm not sure how big the office was, but I understand that Alderson was reasonably senior in that office.

Evan Alderson: I don't think Kenneth Galbraith stole it, stole the idea from him. But I think it might have emerged out of their conversations at the Office of Price Administration, OPA. I think it was probably a very creative time for both of them. They were doing a really interesting thing. They were messing with the markets. So, they had to think a lot about how systems worked and how they interacted.

1944: Alderson forms his consulting practice

Andrew Mitrak: After the war, he sets up a consulting business called Alderson & Sessions. He met Robert E. Sessions, who was his co-founder, at the Office of Price Administration during the war. This later became Alderson Associates.

Ben Wooliscroft: He was a full-service guy from start to finish. Alderson Associates was product development, commercialization, logistics, selling, advertising around it.

Andrew Mitrak: And he had big clients, clients we still recognize these names today, DuPont, Standard Oil, the Rockefeller Foundation, J. Walter Thompson.

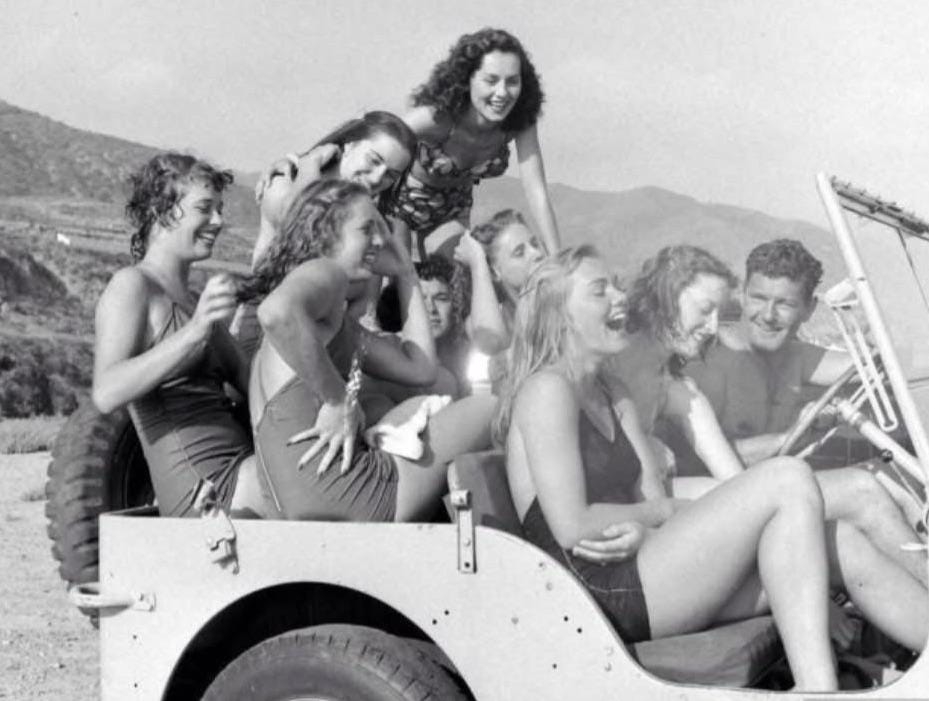

Ben Wooliscroft: He also worked with Jeep. So, his research led to Jeep stepping out of being a military vehicle into being a marketable consumer vehicle as well. He needed to know how people would use a Jeep, what attributes of the Jeep would fit into their lifestyles. The Jeep idea of being on the beach with your Jeep and your girlfriend became quite emblematic of an American experience, far removed from the thought of it being a military vehicle designed to get you into or out of trouble.

Andrew Mitrak: Here's Professor Stan Shapiro, who at 91 years old, is among the few living academics who worked for Wroe Alderson.

Stan Shapiro: Where do you buy baby food? You buy baby food in a supermarket. Sounds like a stupid question. It was Alderson & Sessions that moved it from drugstores to supermarkets. They did a consulting practice for Johnson & Johnson, which wanted to know how its marketing could be improved and what was improved… you're selling it through the wrong outlets! And it also interfered with the impulse purchase.

Usually you go to the drugstore for a purpose. And you go to the supermarket to do the week's shopping, and things are strategically positioned to encourage you to go by all sorts of interesting displays that you had no intention to originally buy. And you're much more likely to get the stuff bought if you repositioned it in the supermarket.

How theory informs practice, and practice informs theory

Andrew Mitrak: Over the course of this podcast series, I've interviewed several professors about the development of marketing theory. I've also interviewed CMOs and executives about how marketing practice has changed. It's exceedingly rare for any individual to excel at advancing either theory or practice. But Wroe Alderson did both. His consulting practice informed his theory and he applied his theory to his practice. Here's how Stan Shapiro summarizes him.

Stan Shapiro: I'd say a genius in blending theory and practice. Nobody before or after in the marketing area has done it as well.

Ben Wooliscroft: Instead of just this very discreet bespoke consulting job, we are going to find out something more that makes this a contribution to knowledge of marketing in general. We will understand more about the world. Of course, the brand died when he died. But we talk about the big four today in terms of consulting companies, he was one of the big two on the east coast of America.

1948: President of the AMA and publishing “Towards a Theory of Marketing”

Andrew Mitrak: He's nominated and he becomes president of the American Marketing Association in 1948. That same year he publishes Towards a Theory of Marketing. What was this theory of marketing in broad strokes and why would he spend the rest of his life working on this general theory of marketing?

Ben Wooliscroft: His 1948 paper in the Journal of Marketing with Cox is towards a theory of marketing. We spend a lot of time on theory in marketing. We've got theories of branding, we've got theories of consumer behavior, a whole lot of different ones, often that don't talk to each other. The idea of theory of is that they are then joined together around some central hub. And the rest of his life before he died in 1965 was really spent trying to make that a reality.

It's hard to put it all into a short bit but I’ve got sessions I give to my students which take a couple of hours. The real nub of it is this idea of heterogeneous supply and demand, markets as places for matching information to work out which the best exchanges would be, and then all the institutions that go around that to do that better.

He produces a theory of exchange, theories of retailing, theories of consumption, theories of distribution, the idea of cooperation and competition being balanced appropriately, the idea of branding is clearly in there, but in its infancy, looking at a lot of the costs involved in information flows, and how that can be improved.

The organized behavior system

Stan Shapiro: The concept of the organized behavior system was one that Alderson had formulated. It was the idea that you're best looking at an activity in terms of the whole range. There's a lot of attention in marketing on micro activity. But let's pay a little more attention on marketing as society's provision. We're not focusing on a micro exchange, we're not focusing even on a marketing channel, but how from beginning to end, people get the mix of goods and services they want, they like, or in some cases, they can only afford.

Ben Wooliscroft: Alderson looked at the world and saw groups working together and recognized that individuals are members of multiple groups. And this is a real departure from what we expect, partly because of our current individualistic world view.

The primary organized behavior systems are the family, the firm. We go and work for a firm because in the medium to long term, we're better off. There are days we don't like it, but we stick with it. And the government is also an organized behavior system. So, these institutions were his building blocks.

Alderson and Functionalism

Andrew Mitrak: Here's a clip from my conversation with Jagdish Sheth on episode seven of this podcast. It's the first time that the name “Wroe Alderson” was brought up on A History of Marketing.

Jagdish Sheth: And there was a whole writing by one single author called Wroe Alderson. He was a brilliant theorist. And he came out with a theory which he called it functionalist. I still don't understand him because he was very complex language even for academics. It's like reading Greek or Sanskrit or something like that.

Ben Wooliscroft: One of the biggest criticisms of him as an author was that he used complicated and new words, which is really rather unfair. I've done reading level analysis of his work. It's not more difficult than Kotler. It's a very lazy excuse to say Wroe Alderson's too hard to read.

Andrew Mitrak: One of the words that comes up a lot when looking at Alderson is functionalism. Could you share what functionalism means?

Ben Wooliscroft: Yes, and functionalism, it's a shame he used that word because functionalism which is a school of philosophy of science where we're looking at the components of a system and how they work together.

So, yes, it's a systems perspective. It's a particular type of system, and in the mid-60s, it received criticism. With the great upheaval in America, the rise of the critical school, functionalism was criticized for excusing things because if there was an institution like the monarchy, functionalism would say, this is the purpose of the monarchy in the system. It sought to explain all the pieces.

Critical scholars would say, no, the monarchy is the appendix. You don't actually need it and you're excusing them because they happen to be there at the moment doesn't mean that they should be there.

If you look at the history of mentions of functionalism in literature, if you do a Google Ngram or something, you see it being really quite popular, and then dropping off a cliff as the word fell out of favor. Had he just said a systems theory, it might have been more palatable and kept going a bit longer.

Were Alderson’s theories too complex to be memorable?

Andrew Mitrak: We were talking about why Alderson isn't as well known today. One idea might be that when I ask, can you define his general theory of marketing? Well, it takes a two-hour lecture. It takes more than that. It takes a lot to do that and it's, in some ways, the people who are remembered, they're kind of the ones that are a little easier to explain.

They have a nice, pithy, memorable phrase like the 4Ps or STP or brand equity, which are all great. They're all important and I don't mean to diminish them in the slightest. But there is a certain memorability to that where you can kind of say that, oh, that's product price place motion, that's the marketing mix. And Alderson doesn't quite have that equivalent.

There wasn't any short quip, acronym, or easy to remember thought. I'm wondering if that idea rings true for you or if you have any sort of idea about that.

Ben Wooliscroft: Very much so. It's all very well to say, “Einstein is E=mc².” But to get to the point where you can actually understand what that means, you've gone through typically an undergraduate education and really thought quite hard. And if we get into things like quantum physics, leading quantum physicists like Feynman and others say, well, there are three people in the world who understand this theory and I'm not sure that I'm one of them.

So, should a theory be hard? That's one of the philosophy of science questions.

1955: Alderson travels to the Soviet Union, becomes an FBI suspect

Andrew Mitrak: Back to Wroe's biography, right when you think things are starting to, okay, I see the line. He's writing a general theory of marketing, he's the president of the American Marketing Association, he's the founder of one of the top marketing consulting firms in America. Yet another just amazing left turn that's like you wouldn't expect is he visits the Soviet Union in 1959 at the very height of McCarthyism.

And this would be like… you wouldn't imagine the president of KPMG visiting North Korea right now. Just imagine the flack that he must have gotten and the FBI list he must have been on, and he's already sort of on the outside being a Quaker, a pacifist, and here he is going into enemy territory, visiting the Soviet Union.

Ben Wooliscroft: So he published a booklet on it. So not only doing it, but then making it public that he had been there. Their travel papers were from the Quakers because you couldn't travel there on an American passport.

Evan Alderson: He was invited along with some other very senior members of the Quaker church. He was very interested, of course, because he was interested in how they deal with scarcity.

Ben Wooliscroft: And he was looking at their systems of distribution. He was looking at where it was efficient or inefficient.

Evan Alderson: It was a kind of a mission, it was fact-finding.. and it was the kind of stuff that wasn't terribly well regarded at the time.

Stan Shapiro: They were kind of curious, what were these people doing, wandering through Russia at a time of Cold War concerns. It wasn't until Mark Tadajewski published that article about him being followed by the FBI.

Andrew Mitrak: Mark Tadajewski is a professor with a passion for marketing history. He performed a Freedom of Information Act request, also known as a FOIA, for the FBI files on Wroe Alderson.

Andrew Mitrak (to Mark Tadajewski): Do you know if a FOIA has ever been done on Wroe Alderson?

Mark Tadajewski: I did it. (Laughs)

Andrew Mitrak: You did? You did it? Oh, wow. That's amazing.

Mark Tadajewski: The paper that I wrote was called "Quaker Travels, Fellow Traveler? Wroe Alderson's Visit to Russia During the Cold War."

The FBI didn't have a clue that he'd gone there. They only found out, the image I had in my head was it seemed to be some guy in an FBI field office who's sitting there reading a local newspaper and Alderson and the Quakers, which is the group he went with. Now, the Quakers are always going to attract attention because they're pacifists. So they need to be watched.

So Alderson goes there. He's really interested in the Russian distribution system, but seeing where it works and where it doesn't. And he comes back and so somebody from the FBI realizes he's been there because he's been lecturing on it at different places. And then, I don't know how this kind of happened. Presumably he's being followed at this point. But Alderson's in a cafe where somebody's asking him about the trip or something along those lines.

It's a long time since I've looked at it. I think he prods him, and he's basically trying to encourage him to say something about the Soviet Union being better. And Alderson wasn't having any of it. He was quite vociferous at the table. He was very, very firm about his views and he's not clearly aligned in any way, shape or form. And that's reported back to J. Edgar Hoover.

1963: Marketing and the Computer

Ben Wooliscroft: Stan Shapiro, he was deeply involved in some of the work that Alderson did.

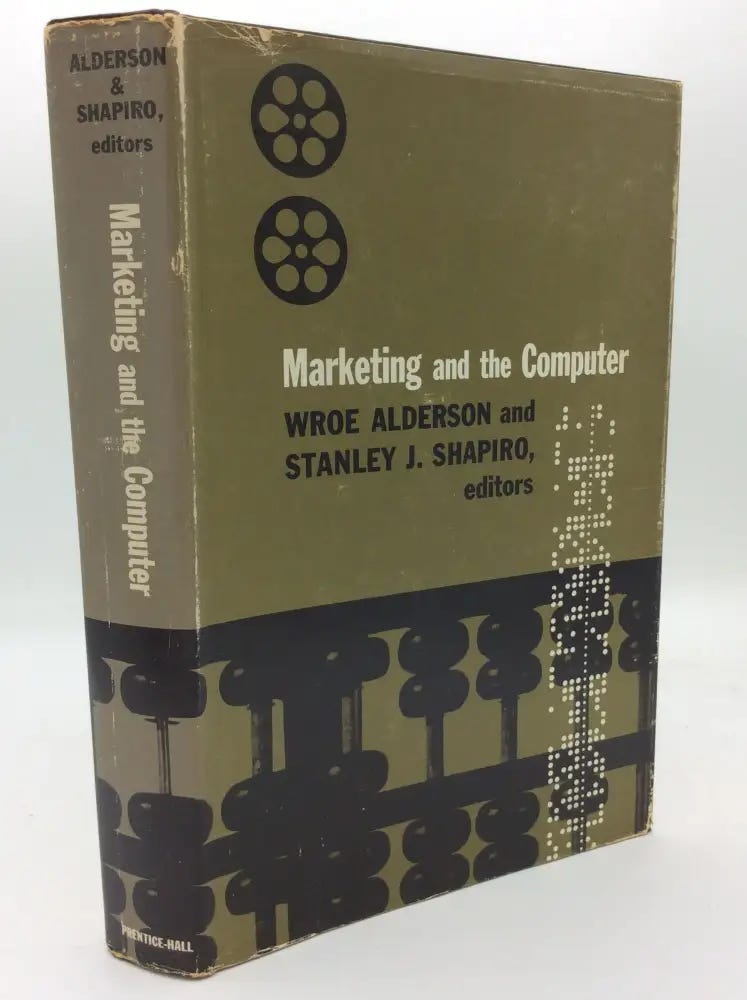

Andrew Mitrak: One of Stan Shapiro's collaborations with Wroe Alderson was the 1963 book, Marketing and the Computer. It's among the first books to analyze the implications of the computer on modern marketing.

Stan Shapiro: And remember, let's make it clear. I didn't work with Wroe Alderson. I worked for Wroe Alderson. And there is a difference in that. Remember, this was the early days of computer. You cannot imagine. And there was this enormous room, which had one of the early computers. It was the size of a conference room. And it was felt and well anticipated, this was going to revolutionize things. And so he decided to put together this book.

Andrew Mitrak: Here's a quote. "Advancing skill in handling numerical data is a major facet of intellectual and material progress. Man, the marketer, is first of all man, the counter, whether he keeps his score on clay tablets or magnetic tapes. The perennial questions of the marketplace are how many and how much."

They also anticipated the use of computers for better forecasting. Another quote. "The constant pressure for better forecasts may occasion a deep regret for past business records thrown away. It is impossible to foresee all the possible uses of information which appear relatively useless today."

Stan Shapiro: I think there were some important insights, but we were there and we were there early. And that was all Alderson wanted to do. He wanted to be there intellectually early in a number of areas.

Marketing Theory Seminars and Alderson the educator

Ben Wooliscroft: Associated with the consultancy, but driven through the universities, was the marketing theory seminars. They had meetings by invitation only. And so, if you're the deputy vice president marketing for Firestone or Bell Telephone or Coca-Cola, and you got an invitation from Alderson to come to this, you would come. As well as senior executives, Wroe Alderson chose the young scholars he saw across the country, and they were invited. And of course, if you got invited, you wanted to go because this was the president of AMA, the leader of Alderson & Sessions, the Wharton professor.

Stan Shapiro: And he was a character. He was an event. Now, we're talking about a heavy set man, didn't dress too well, kind of a little awkward in his manners. Very bad classroom lecturer, brilliant across the beer at the faculty club. That's where Wroe Alderson was at his greatest.

1965: Wroe Alderson’s death

Andrew Mitrak: Although he was athletic as a young man, Alderson enjoyed food and drink and by the mid-1950s, he was seriously overweight. Wroe suffered his first heart attack in 1955. And despite attempts to moderate his diet, he had health issues for the remainder of his life.

Evan Alderson: This is a story of a major event in my dad's life that I never witnessed. But I heard about it from my mother when she called to tell me about my dad's death in 1965.

They had a place near Royal Oak in Maryland, which was near an arm of the Chesapeake Bay that came up and they loved it there. And you hear from what you've read that that was his retirement place and he was pretty much by that time retired from his work at Wharton school and he was spending more and more time in Maryland and that was his place. And he loved it.

He had boats that he didn't drive anymore, but he loved to go out on his paddle boat just off the shore. There was a little beach on the property and he went off just a little way out and then came took his paddle board back.

And that morning, he'd gone out on his paddle boat. And he had, I imagine, that when he, the way I construed the events is that when he was coming back on his paddle board, he had his third heart attack.

He knew what was happening. And he was out there, maybe not all that far, but maybe 50 yards to shore or something. And he was having his heart attack. And he faced this ultimate dilemma of what to do next.

He tried to make it back to shore.

And I can imagine this guy, I think I think of a lot… using all his strength… everybody he was, everything he knew… trying to get back on his paddle board and making it to shore and taking one or two steps onto the beach… and falling dead.

Obviously, that story is very moving for me. And it's full of love and compassion when I think about it. But I also think it was very much about his character and who he was and his determination against many odds and how he could manage best in an absolutely horrible situation.

Andrew Mitrak: Thanks for sharing that. That's deeply moving to hear that. I obviously didn't know the circumstances of his passing… and in a way, it's beautiful that it happened in a place that he clearly loved, that he loved the water and the Chesapeake and this meant a lot to his family…

But going to shore while you're facing that, it's really a feat of strength and shows that you don't want to be lost at sea either. You don't want somebody else to discover you, you don't want to become somebody else's problem.

Evan Alderson: Exactly.

Andrew Mitrak (to Evan Alderson): Thanks for being so open and sharing about your family, your father. This has really been just a moving conversation to hear about.

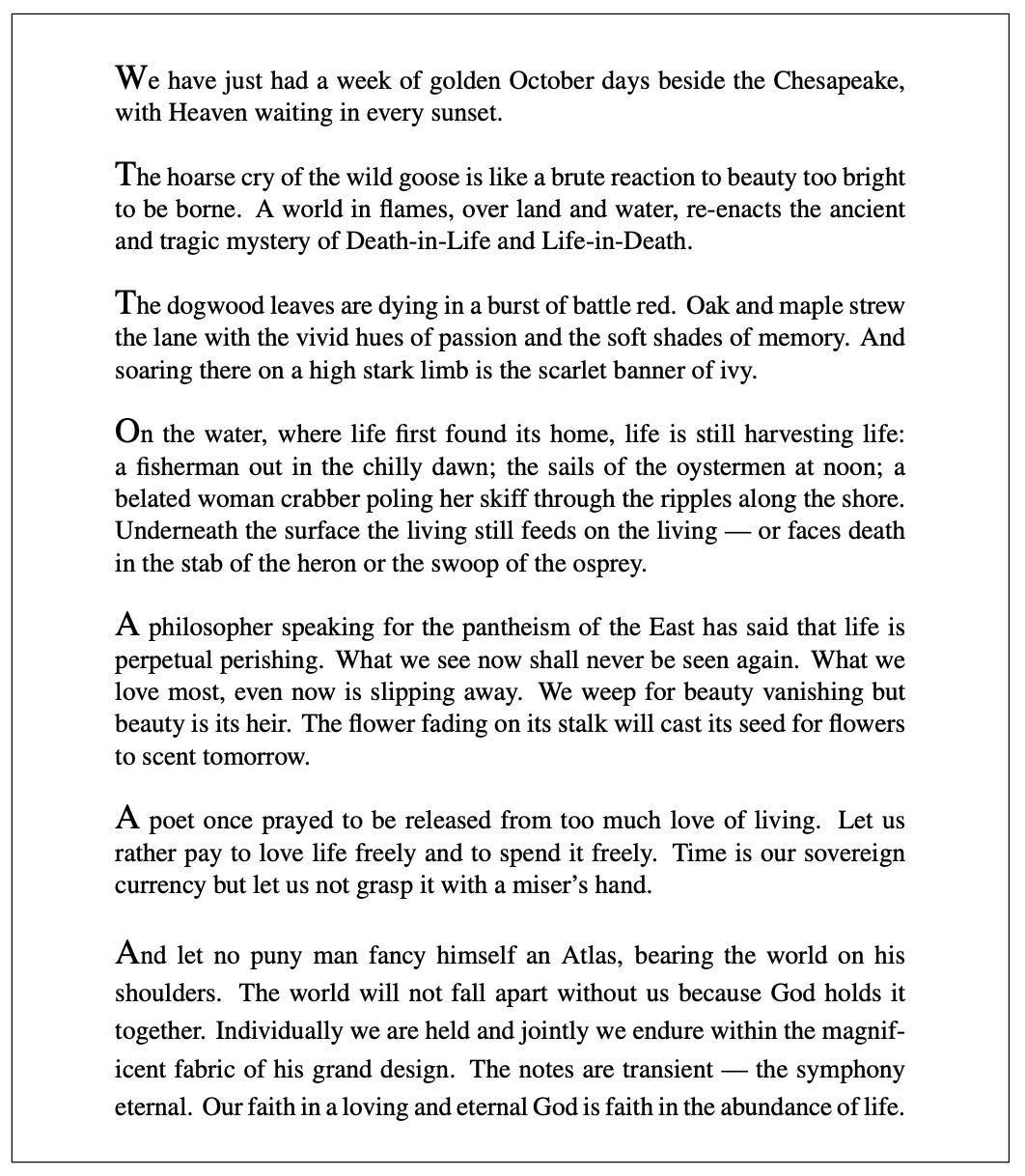

Andrew Mitrak (Narrating): Wroe Alderson wrote poetry for his wife, Elsie, and was known for his eloquence when he spoke at friends meetings among Quakers. He wrote about the fleeting beauty of the Chesapeake Bay, the location where he died, in what became known as The Autumn Prayer. I'm going to read a few of my favorite lines that seem appropriate.

"We've just had a week of golden October days beside the Chesapeake with heaven waiting in every sunset... What we see now shall never be seen again…. What we love most, even now, is slipping away…. Time is our sovereign currency, but let us not grasp it with a miser's hand…. The notes are transient, the symphony, eternal."

Wroe Alderson’s legacy and place in marketing history

Stan Shapiro: When Alderson left, the driving force was gone.

Ben Wooliscroft: It seems that wherever he was, he was one of these very charismatic and active leaders. So he would step in and drive things and be engaged, be it church, be it university, creating whole institutions like the Marketing Science Institute, leading the AMA. And yet he spent so much time involved with the market at the bottom, where the customer hits the road, that I think that really added a lot of value to his theories.

Stan Shapiro: Now, as to why people haven't heard about him, you take a PhD course in marketing, what you do is you learn more and more each year about less and less until you become a leading authority on next to nothing at all. That has been the focus. Alderson is wide-ranging.

Ben Wooliscroft: I was going back to second year, did my honors degree and in the honors year, they said, and now we're going to talk about Wroe Alderson for one class. And I was upset!

Here is the person who gave us the most complete theory of marketing, who was the most connecting person in the discipline, and I had to get to fourth year to hear about him.

To be honest, I was very lucky because most universities in the world won't mention Wroe Alderson at all. And this had stuck with me, the sense of injustice that our leading scholar had forgotten.

Andrew Mitrak: So now you know more about the life and influence of Wroe Alderson than almost every other marketer in the world.

So, was Wikipedia right? Is he really the most important marketing theorist of the 20th century and “the father of modern marketing”? I'm still not equipped to answer that, and I've come to think of labeling any individual person as the father of an entire discipline is kind of a frivolous exercise.

I'm also not sure that honor would sit well with a Quaker like Alderson, who saw all men as equals and who rejected offers of honorary PhDs because he hadn't felt like he earned the title. But I hope you agree that Wroe Alderson lived an inspiring life. I'll give Stan Shapiro the final word.

Stan Shapiro: Wroe Alderson was not a person, he was a personage. He was the most important figure in the mid 20th century in the marketing. Now, there were people who chided me for not giving him the whole century, you might say, but there were one or two other people like Philip Kotler for whom I could make the case, but there's no question in my mind, he dominated that middle period in intellectual thought. I'll sign off with that.

Here is the complete version of Alderson’s “Autumn Prayer” which I read excerpts of:

I’d like to give a special thanks to professors Ben Wooliscroft, Stan Shapiro, and Evan Alderson for their participation in this podcast about Wroe Alderson.

I’d also like to thank my friend Scott Morris of Waka Seattle for providing creative feedback during the editing process of this episode.

This episode required ~10X the effort of my usual conversational episodes. I had a lot of fun creating it. If you liked this episode please consider sharing it with a friend or posting about it on your preferred social network.

If you’d like to send me a note about it, email me at hello@marketinghistory.org.