A History of Marketing / Episode 27

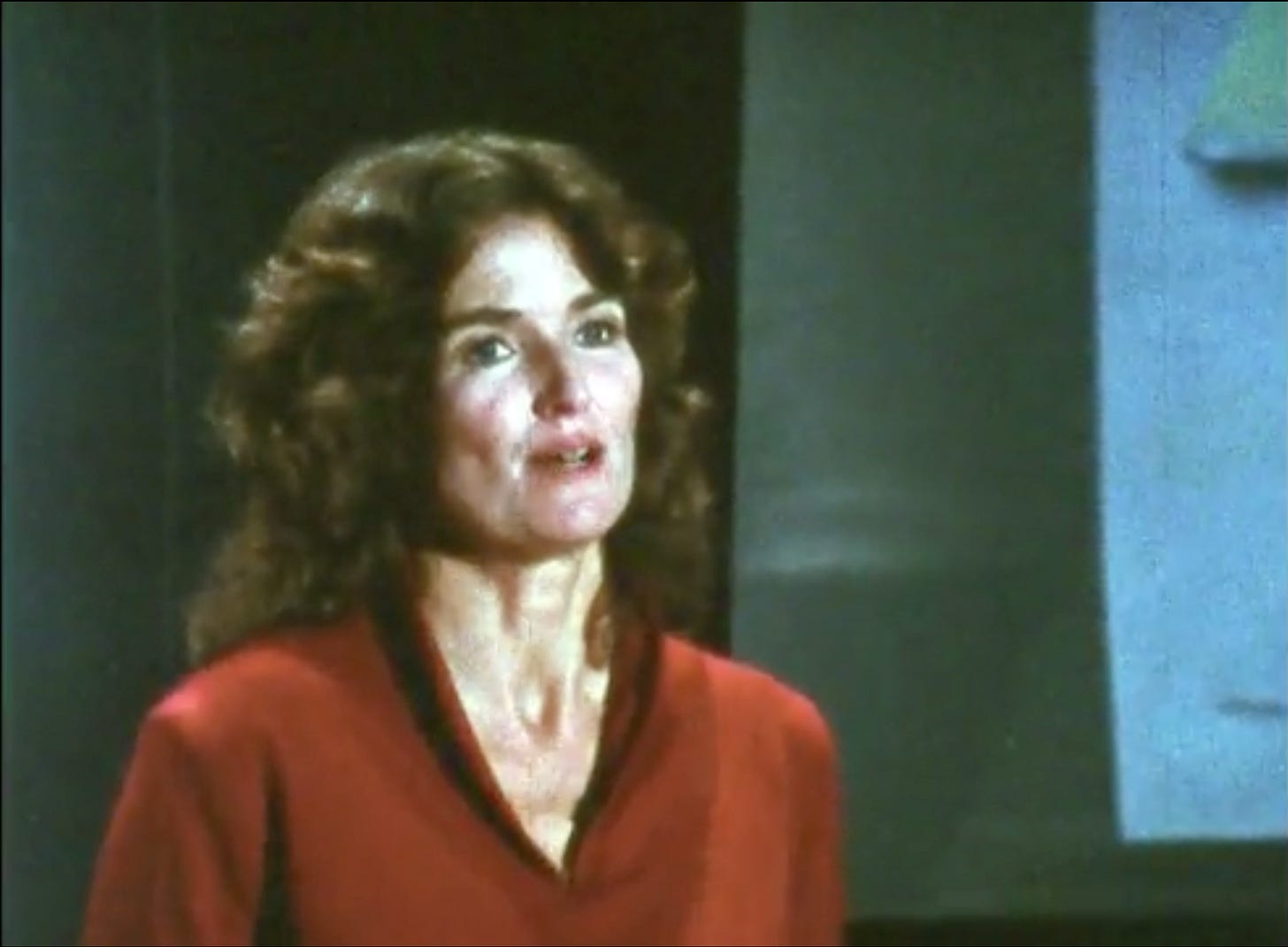

This week, I’m excited to share a timely conversation with author, filmmaker, and activist Jean Kilbourne. Kilbourne is recognized as the pioneer of feminist advertising criticism, and is best known for her influential documentary series, Killing Us Softly.

Since its release in 1979, Killing Us Softly has been essential viewing in classrooms across the United States, draws attention to the objectification of women’s bodies, the promotion of harmful stereotypes, and the effects of advertising on the self-image of women.

In past episodes of this podcast, I’ve mostly focused on the positive side of advertising. We’ve covered the history of advertising and the Creative Revolution, explored the science of persuasion, celebrated iconic spots like Apple’s "1984" Ad and classic Coca-Cola campaigns, and analyzed milestones in measuring advertising’s effectiveness.

But advertising is not without its critics, and a history must cover the good alongside the bad. As a marketer myself, I think it's important to listen and learn from critics so we can avoid making the mistakes of others.

There is no better guest for this conversation than Jean Kilbourne. Kilbourne has been a trailblazing force for more than 50 years, and in our interview she brings an analysis that is thought provoking, witty, and entertaining.

Now, here is my conversation with Jean Kilbourne.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Transcript note: I use AI to transcribe conversations. I review the output but it’s possible there are errors I missed. Parts of this transcript have been edited for clarity.

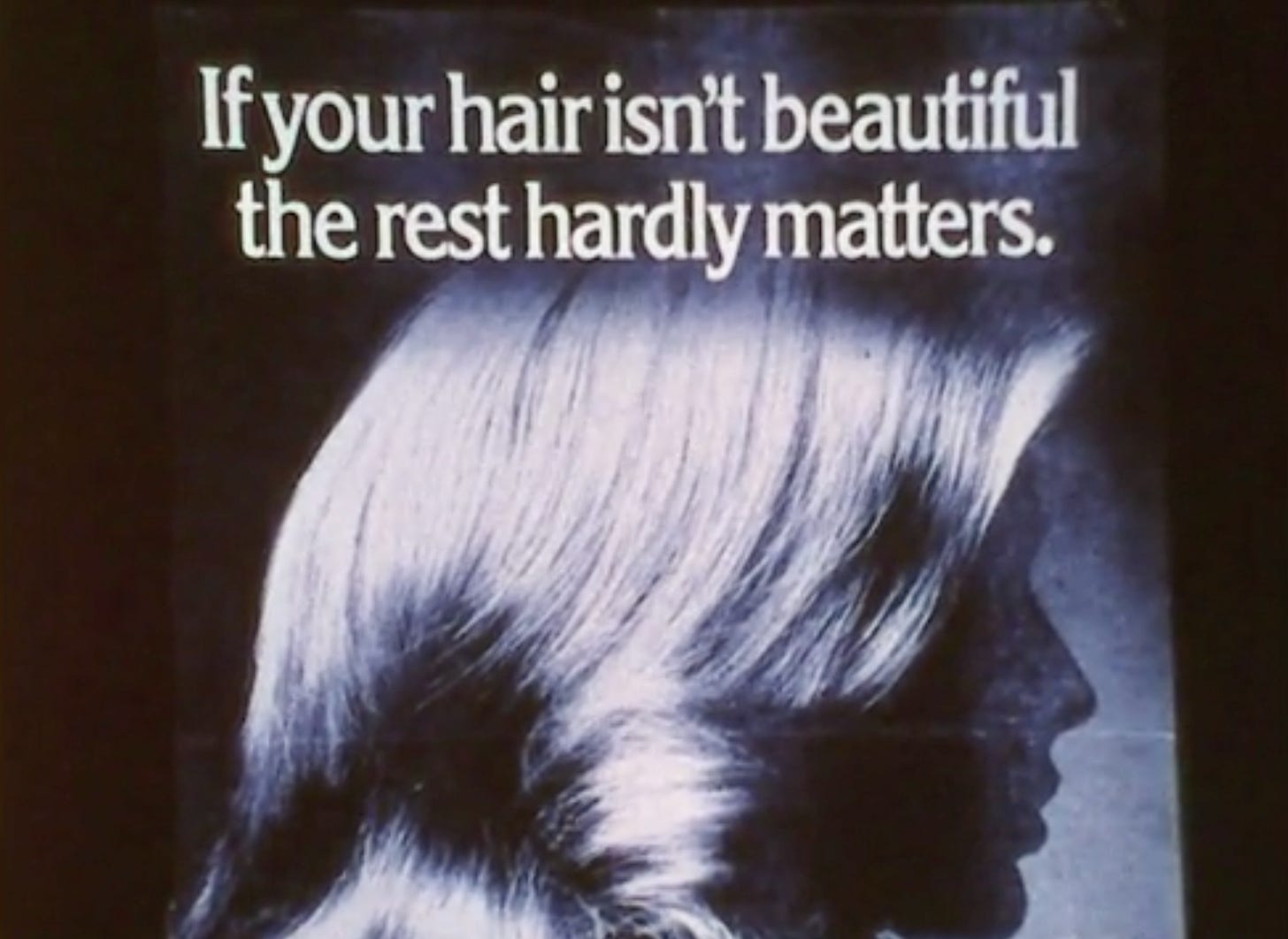

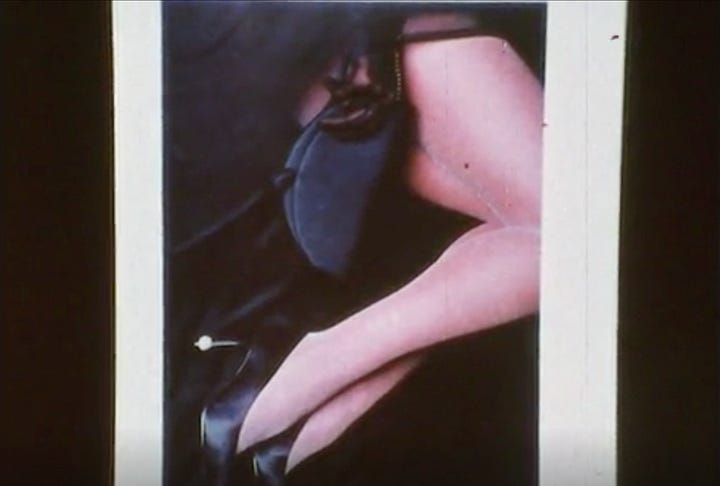

Content note: I’ve included images of advertisements from “Killing Us Softly” in the transcript to illustrate the conversation. There are some ads you will likely find distasteful and potentially upsetting. If you prefer to avoid these, you can listen to the audio or watch the YouTube video instead of scrolling further.

Andrew Mitrak: Jean Kilbourne, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Jean Kilbourne: Thank you so much. It's a pleasure to be here with you.

How It Started: An Awful Ad In A Medical Journal

Andrew Mitrak: I want to start back in the late 1960s or so when you began cutting out and saving those first advertisements. Can you take us back to that moment? Was there a specific ad that stood out to you or what motivated you to first find an advertisement and say, "I need to preserve this"?

Jean Kilbourne: I sometimes say, in 1968, I saw an ad that changed my life. And I did. But I have to go back a little bit as to why I would have been interested in this ad. I was involved in the anti-war movement, like a lot of people in my generation, and then went from that to the second wave of the women's movement. So I was already interested in feminism and all of that. I went to Wellesley College, and then I had to go to secretarial school to get a job. So my options were very limited. I was a waitress, I was a secretary, etc.

So, I had a job putting ads into The Lancet, the British medical journal. Simply placing the ads into the magazine. And one of these ads was for birth control pills called Ovulen 21. It featured a smiling woman's head, and it said, "Ovulen 21 helps you remember by weekdays rather than cycle days." The gist of the ad was that women were too stupid to remember our cycle days, but we could remember the days of the week.

I remember looking at this, and it wasn't the first ad I've ever seen that trivialized or stereotyped women, but there was something so atrocious about this particular ad. And I remember thinking, this is really awful, and it's not trivial. This is going into a medical journal. It's not trivial. So that was the first ad I took home, and I put it on my refrigerator with a magnet. And then I started noticing and collecting other ads.

Andrew Mitrak: So you put it on your refrigerator to collect it. You didn't have a vision at the start of turning these into a slide presentation. It was just to preserve the evidence of this crime.

Jean Kilbourne: That's exactly right. And of course, there wasn't even a model for doing a slide presentation on this. Sometimes people say, "Did you set out to do this?" I mean, there wasn't anybody who was sort of traveling around with slide presentations, or at least not on this topic, certainly.

But I did become interested enough, and I began to see patterns in the ads. I had maybe 10 or 15 ads on the refrigerator by then, and I began to think these are related in some way, and they really are saying something about what it means to be a woman in this culture in terms of advertising and the mass media. So then I bought a… I got a camera, but I got a macro lens, I got a copy stand. This was over 50 years ago, so it was really a time when that's what you had to do. I had to teach myself how to do all that, and I turned the ads into slides. But even then, I didn't think this was something I was going to make a career out of. I was just very interested. And then I became a teacher. I was a high school teacher for about three years, and I began to use the slides in my classes.

Seeing Patterns in Harmful Advertising Tropes

Andrew Mitrak: What were the other ads? What was the range of ads that you were collecting?

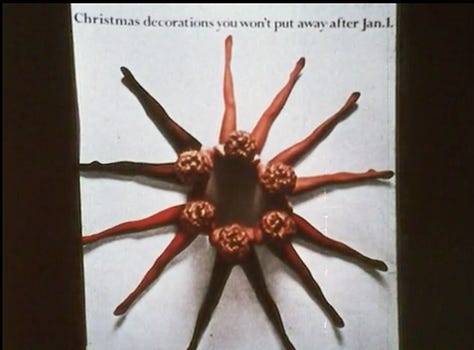

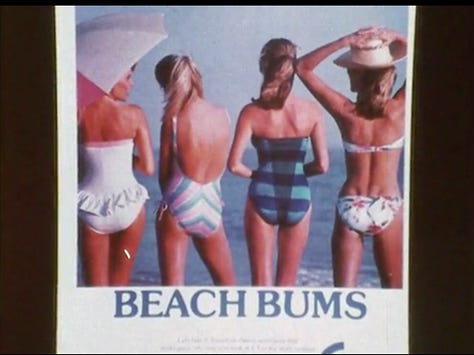

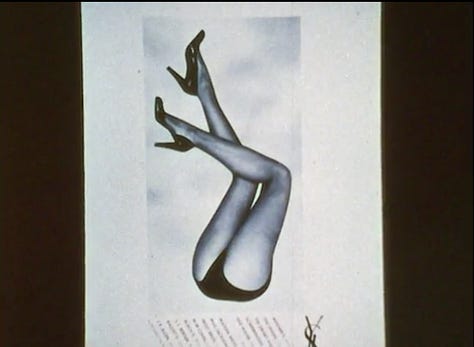

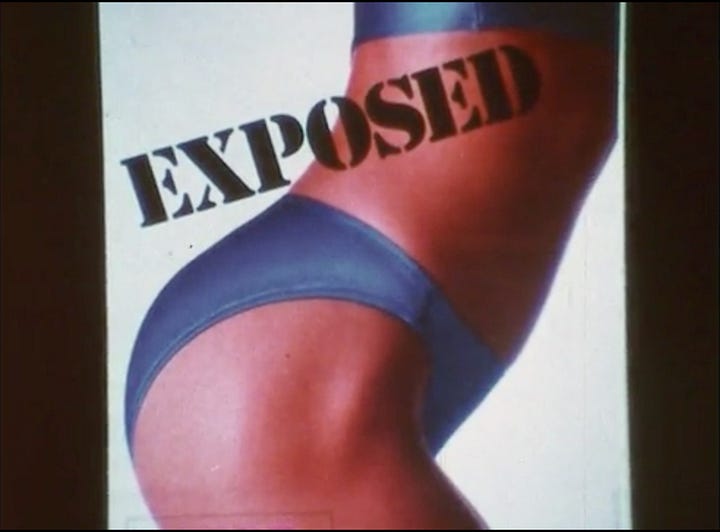

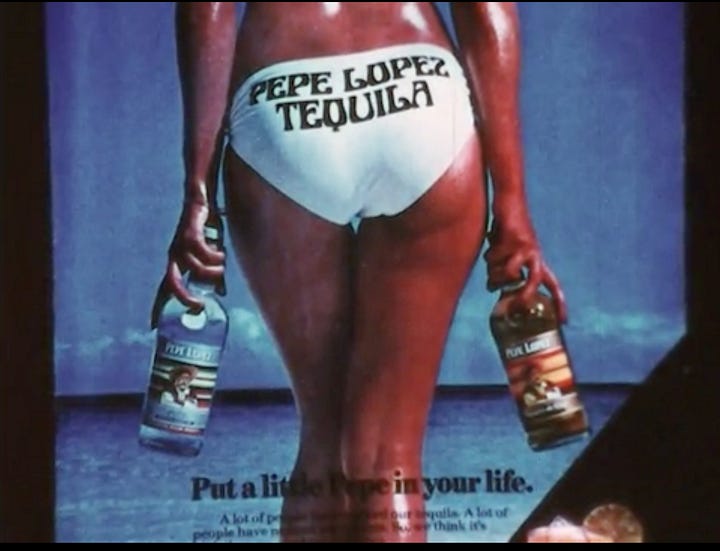

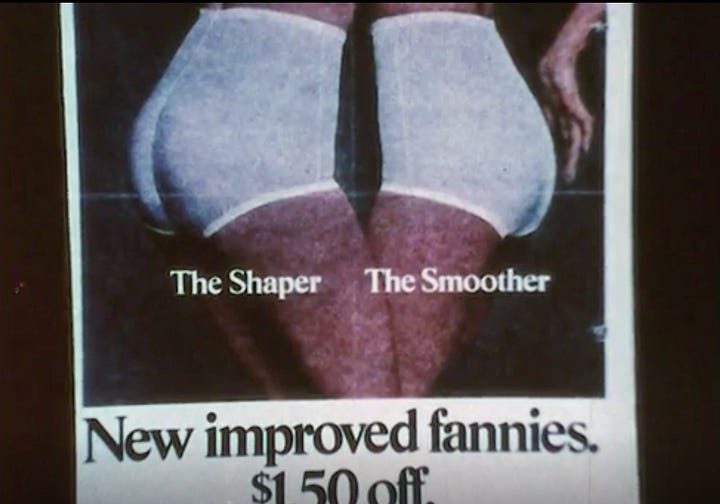

Jean Kilbourne: Well, some of them were just the ideal image of beauty that was everywhere and was so much the same. Some of them, I noticed that women's bodies were dismembered in advertising. So that many, many ads featured, obviously, women's breasts—a huge way to sell products—but also a woman's torso or a woman's legs. And this was not happening to men. So I noticed that. And that seemed to be saying something about the dehumanization of women and the objectification of women.

There were also quite a few ads that were violent in one way or another, that seemed to portray battering or rape in a kind of jokey sort of way, usually. But I noticed those too, and those of course stood out for me. So there were many different patterns that I saw.

Andrew Mitrak: When you use the word "dismembered," it's a really violent word. Sometimes, though, it's also sort of tightly cropped where the camera frames on a piece or a portion of someone's body versus the entire human. Is that sort of the idea behind that?

Jean Kilbourne: Well, sometimes, but sometimes it literally, the ad would simply feature a woman's legs, or a woman's legs sort of in the air. Or sometimes, often, it would feature just a woman's breasts. So it wasn't just the way it was framed, it's just the way it was shot. And that seemed to me particularly dehumanizing. I mean, I used the word dismemberment on purpose because the body really was dismembered. And again, this wasn't something that was done to men.

Also, there were many ads that featured women without heads, basically. I mean, the ad would start from the neck down. And that seemed sort of something that was not happening to men either, and that seemed to be very dehumanizing and objectifying. The other thing I noticed was the body language of women, that it was often so trivializing.

And often, one of the things that I talked about in the original version of Killing Us Softly, and still do, was the sexualization of little girls. And that was happening even then. So little girls were presented in sexualized ways, and adult women were infantilized. Adult women would be portrayed dressed like a little girl or with a lollipop or a headband or something like that. So that was something that stood out too when I started collecting the ads.

View the original 1979 version of “Killing Us Softly” at Archive.org

Andrew Mitrak: So the initial collection, you first presented these in a high school class. What was sort of the context for the initial presentation?

Jean Kilbourne: Well, I taught high school in the late 1960s, so I got away with a whole lot. I was able to teach whatever I wanted to teach. I was an English teacher, but I created a film study class. And then I created a women's study—I mean, I did things that would be impossible to do today. We were not teaching to the test, to put it mildly. So I just, I think I used this in a unit I was doing on probably on women's issues, but also maybe on media. And so I did use it, in the beginning, I used the slides in my high school class. They were incredibly effective in terms of teaching the students not only about issues about women, but also about advertising and about marketing.

Selling “A Perpetual State of Dissatisfaction”

Andrew Mitrak: One of the themes of your work is that the advertising industry's goal isn't just to sell an individual product, but to sell a perpetual state of dissatisfaction. That they're not just selling lipstick, but they're selling the need for lipstick. Was there a moment or a specific ad that shifted your understanding about the overall goals of advertising or when did this bigger picture come into play?

Jean Kilbourne: There wasn't a particular ad, but I did notice that most of the products that were being sold were really the same. That was one thing. The kind of lipstick or the moisturizer or whatever. In fact, I would go sometimes to a CVS or a drugstore and look at the brand-name items versus what was being sold cheaply. And the ingredients were almost always the same.

And so that made me realize that what they had to be selling was an image. They had to be selling something beyond the lipstick and the moisturizer. So that was one thing. Another thing that became clear quite quickly is that many of the products that were being sold to women didn't really work. The so-called anti-aging products, for example, which almost always featured a very young woman smearing on this cream. And also the diet products. They, of course, did not work because if they did, then that would get out. Of course, the world has changed since then, and now there are diet products that do work. And not so much that there are anti-aging products that work, but people have surgery and all kinds of other ways to do that. But 50, 60 years ago, that wasn't the case. So these products seemed to be not only the same, but they actually weren't working. So all the more reason that they had to be sold by selling something other than the product.

And I'd also been influenced by… there wasn't much out there about advertising in those days, but I had read Vance Packard's book, The Hidden Persuaders, in high school, and I remember being fascinated by that. And I also had read Erving Goffman's book on Gender Advertisements, which was also… that was mostly about the body language and the way in which women are posed and everything. And that was very important to me as well. So those things informed my consciousness about all this.

Andrew Mitrak: Erving Goffman, did he also write about the masks that we wear and that there are different personas? Am I remembering the right author?

Jean Kilbourne: Yeah, he's a sociologist who wrote about a lot of things, but I think only that one book was about gender, and it was very specifically about, again, not just body language, but things that still are true—the way in which women often cover their mouths in ads or do the little girl thing, become sort of ridiculous or trivialized. He pointed that out early on.

Bringing Advertising Criticism to the Feminist Movement

Andrew Mitrak: So you're drawing from some of these sociologists like Goffman, others who have written about advertising, and then you were doing a lot of your own research, literally through magazines and just what you were finding and piecing this together through your independent research.

Jean Kilbourne: And I had a feminist point of view, of course, which Vance Packard did not, and so that made it different as well.

Andrew Mitrak: From your feminist point of view, what were your key inspirations there? Who was inspiring you and what literature were you reading?

Jean Kilbourne: Well, that's kind of interesting because nobody was talking about advertising or the image of women in advertising at all. And in fact, most feminists in those days felt that it was a trivial issue. Everybody thought it was a trivial issue. What I heard most of all people would say is, "I don't pay attention to ads, I just tune them out." Everyone believes that they're somehow not susceptible to advertising, which of course makes the advertiser's job so much easier because it's beneath our radar.

But what feminists would say to me was, "We don't have time to deal with trivial issues like the image of women in advertising. We're dealing with serious issues like violence against women." And I would say it's related. When you objectify women, you set them up for violence. In fact, it's a necessary step for violence, is to dehumanize the person you're being violent to. I don't think it's really possible to be violent to someone you consider an equal human being, but it's very easy to abuse a thing. So that was my argument, but it took years before even feminists took the issue seriously. So when I started, I don't think there was anybody else who was really looking at this in any kind of serious way.

In terms of the other influence, I was influenced by the consciousness-raising groups because that was the second wave of feminism. We got together in small groups and told the truth about our lives. The poet Muriel Rukeyser has a wonderful line, "What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open." And that is what happened in these consciousness-raising groups, that we realized we were not alone. Those of us who've been raped, those of us who've been sexually harassed, those of us who've been in abusive relationships, we were not alone. And up until that time, I've been sexually harassed all the time, and I thought it was something I was doing wrong, or that I was the only one. So just to learn that this was happening and it was happening in a very systemic way was incredibly important.

When Did Harmful Tropes Emerge in Advertising?

Andrew Mitrak: You recognize that this is happening in a systemic way. Part of this podcast is taking a historical view on marketing and advertising. Do you have a sense of when this emerged—when unrealistic beauty standards or harmful stereotypes of women started to appear in advertising? Was it there from the beginning or were there moments that punctuated it becoming a more prominent part?

Jean Kilbourne: You'll probably know more about this than I do, but in the beginning, I think, of advertising, advertising was designed to give information, right? It was sort of something in the newspaper telling people where to go for a sale or something, or in the very beginning, signs on buildings: "Here's a tailor, here's a…" that sort of thing. Then it became something that was very, very different. It became something that again was selling products that people often did not need, or selling them using images that were harmful and destructive in some way.

I used to say to my audiences sometimes that if an ad is giving honest information about a product that we need, I have absolutely no problem with that, but can you name an ad that does that? A national or international ad. And really, hardly ever could somebody say, "This is honest information about a product that we really need." So I think that was part of what happened. As the whole media changed with television and all of that, it became much more advertising-based and commercially-based so that the point of the programs and the magazines and everything was to sell audiences to advertisers. That was when things really flipped and became very, very different than they'd been in the past.

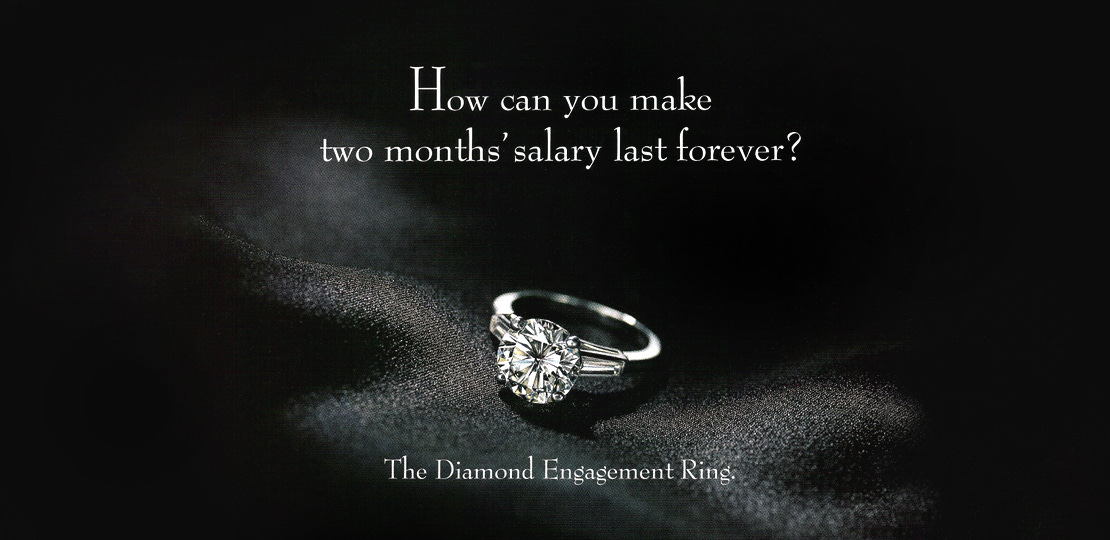

De Beers and “A Diamond Is Forever”

Andrew Mitrak: One that you've spoken about that is a historical one is De Beers and the idea that "A diamond is forever," and that we didn't feel the need to purchase things like engagement rings, but this company, through creating this need or creating this dissatisfaction of somehow your love of somebody is measured by the size of a ring… that's one that strikes me as a historical example. I think it was in the '40s or so that that one appeared.

Jean Kilbourne: Absolutely. And I don't think diamonds were even particularly precious or desirable really before then. That's such a good example of how a company created a need.

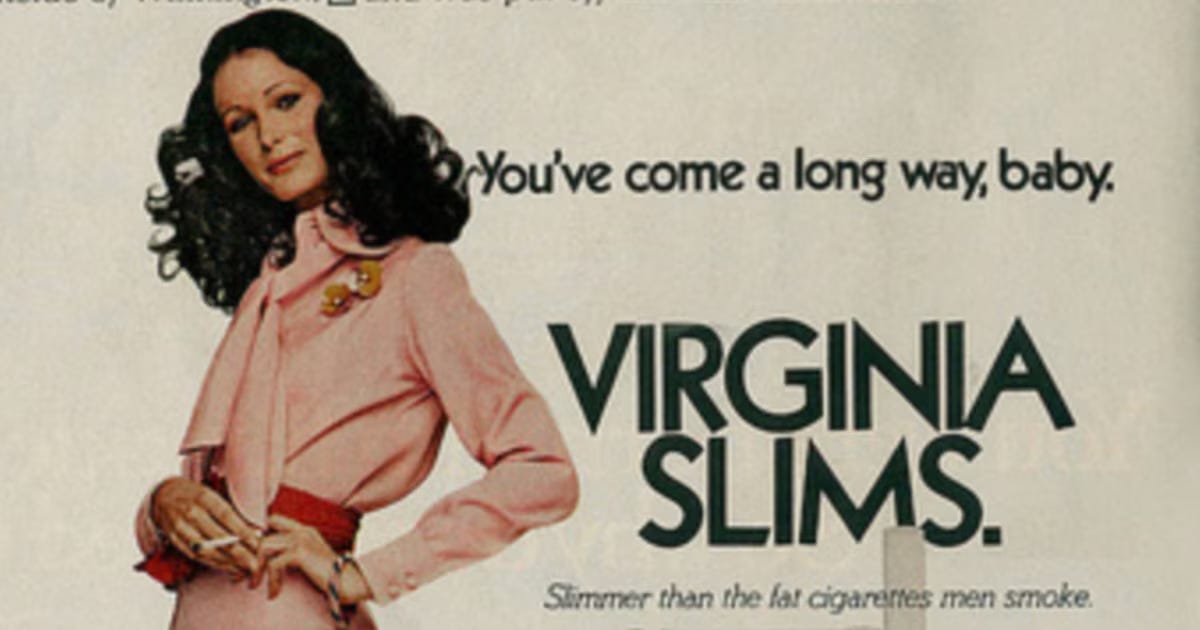

One of the earliest examples too that I use a lot comes from Edward Bernays, of course, who was the father of public relations. He had the brilliant idea in, I think it was 1929, to march with the suffragists—he hired women to march with the suffragists in the Easter Parade, I think. And then to light cigarettes. And that was an amazing thing to do then, for women to smoke in public. And when they were asked about it, they would say, "These are torches of freedom."

So what he did was he linked smoking with liberation for women. And then of course, that went on. We saw that with Virginia Slims, "You've come a long way, baby" was a direct line from that. But what an amazing thing to link an addictive product with liberation for women, with freedom. He was one of the starters of that sort of thing.

Andrew Mitrak: I recorded an episode with Bernays’ biographer [Larry Tye]. We talked about this and it’s sort of co-opting a movement for good with commercialization. In this case, the commercialization of a lethal product that’s killing its customers.

Jean Kilbourne: Well, actually I did my doctoral thesis on the co-optation of women, the liberation by the media, by the advertising. I’ve always felt that capitalism always co-opts any kind of radical movement for change. Whether it is women’s liberation or the green movement, basically anything that’s going to bring about radical change in society that might harm shareholders’ profit is going to be co-opted. We are seeing that more and more of that now.

Kilbourne’s Experience as a Professional Model

Andrew Mitrak: A piece of your own history that we haven't talked about yet is that you were once a model in London in the 1960s, and you've spoken about how this was a formative experience for you. Do you have any reflections of this time, and did your later study and analysis of advertising change your own memories and reflections of it as well?

Jean Kilbourne: I didn't really set out to be a model, but again, as I said, I went to Wellesley College, and then I went to secretarial school. The options for women were so limited. I was a waitress, and I was a secretary. But modeling was one of the few jobs available to women that was lucrative. And so, when I was young, I was often encouraged to enter beauty contests and to model. I was always ambivalent about it, always, because for one thing, it seemed sort of awful to rely so much on something like one's looks, one's image. But again, it was lucrative, and also in those days, there was a lot of encouragement to do it. Nobody saw anything wrong with it. It was like, "Wow, you have this opportunity, you should do it."

But I found it incredibly depressing, actually, and dehumanizing. I also found it interesting that the other models, the ones who were really doing this, were among the most insecure group of women I've ever known because if your value depends on your looks, you're always going to be comparing yourself to somebody else, or dreading growing older. And of course, in those days, growing older meant turning 30. So I didn't, I would do it, and then I would back away from it. The other thing about it is there was an incredible amount of sexual harassment, and that just sort of came with the territory. And the number of times that I was told I could really make it big if only… So that was very depressing as well. So it was not a career, by a long shot.

Andrew Mitrak: I'm sorry that you went through that. It's disgusting and makes me angry and sad. And also just that it's a profession that so many young people aspire to. It's glamorized in a way, and really it's a career that even the very small number who are successful within it seem, as you're mentioning, to have deep insecurities or face other challenges.

Jean Kilbourne: Thank you. It's also changed tremendously because when I was young, models were not famous. You did not know the names of them. Maybe you knew Jean Shrimpton, but you really didn't know the names of the models. They weren't celebrities. And then, of course, that changed, and the models became supermodels, and then they became very famous. Also, when I was young, we didn't really expect to look like the models. We didn't measure ourselves against them all the time the way that is happening now. So it was a very different world.

The Viral Spread of "Killing Us Softly"

Andrew Mitrak: Jumping around a little bit, you had been putting these slides together for your high school courses. Do you remember the first time you gave what became the "Killing Us Softly" lecture? What was the audience and what was the initial response to it?

Jean Kilbourne: Well, I remember the first time I gave it to a large audience. I did it in classrooms, then I got invited to do it for smaller groups here and there. But the first large audience was at Concord Academy in Massachusetts, a very progressive, wonderful school. I was invited to speak to the entire student body, which I think would have been about 400 or 500 people. I was so terrified that when I was driving there, I seriously considered driving off the road. Not to kill myself, but just to be incapacitated. The other thing I thought about was phoning in a bomb scare, which in those days did not land you in federal prison, but it would have… I was terrified because I was very afraid of public speaking. Most Americans are. In fact, studies say that we fear speaking more than death, which I've always found kind of funny. But that didn't mean I wasn't good at it. I was actually always pretty good at it, and I actually enjoyed it, but I was very afraid of it.

So that first big audience was hugely important because had it not gone well, I'm not sure what would have happened. But it went very, very well. I got a standing ovation, and they had wonderful questions, and they stayed around to talk for a long time. So it was very, very heartening. So I do remember that lecture very, very well.

And another thing, in terms of the very first lectures I gave, what surprised me the most when I first started doing this was that people laughed. I hadn't set out to be funny. And I also never wrote out a script; everything I did was sort of ad-lib. I remember the first time that I said, talking about the ideal image, that, "She is completely flawless, she has no scars or blemishes, indeed, she has no pores." And everybody laughed, and I thought, "Wow, that's fun." So I keep using that line. And I then started encouraging people to laugh at the ads because I thought it was good to ridicule the ads. So then the presentation became actually very funny because the ads are so ridiculous. And I think that had a lot to do with the success of "Killing Us Softly"—that it was funny, and it was not what people were expecting. They were expecting, I don't know, a polemic or something, but it was not what they were expecting.

Andrew Mitrak: It is actually funny. It's also entertaining to watch. It doesn't feel like homework. It's sort of like eating your vegetables but also having some sugar with it so it goes down a little easier.

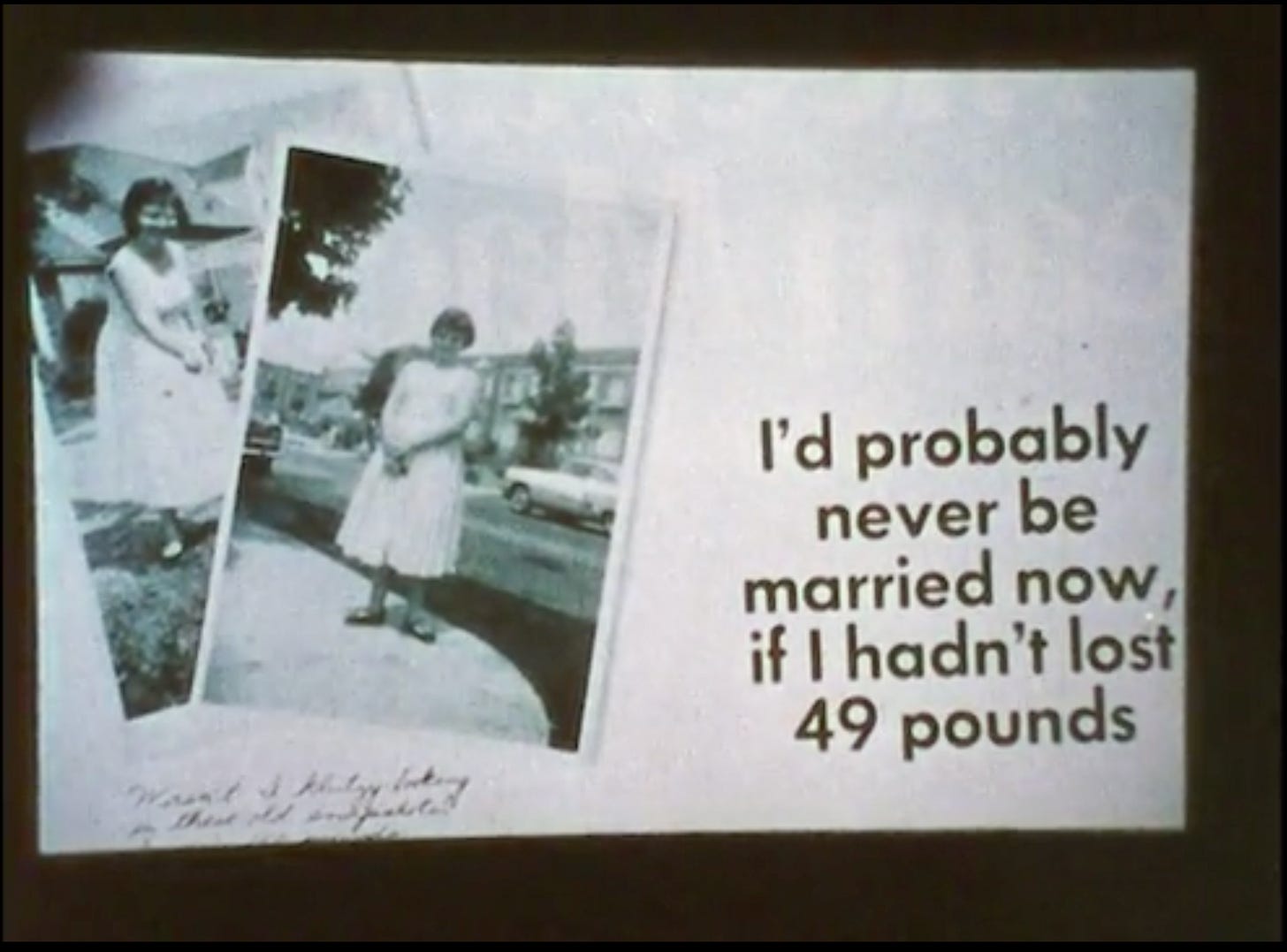

Jean Kilbourne: Some of my best lines, by the way, came from my audiences. One of my favorites was an ad, this was a long time ago, for a diet product, and it said, "I'd probably never be married now if I hadn't lost 49 pounds." And one woman shouted out that that was the best advertisement for fat she'd ever seen. The audience broke up, and I started using that line all the time, too. And the other thing is, in those days, when I was starting out, people were saying feminists had no sense of humor. That was a big thing—that we were ugly, and we were depressing, and we were man-haters and all of that, but we had no sense of humor. So I certainly wanted to dispel that.

Bringing “Killing Us Softly” to College Campuses

Andrew Mitrak: Now, these were popular lectures as soon as you started getting these big audiences, and you traveled the country, right? You traveled to different colleges. I read online—I can't believe everything I read on the internet—but it looks like you were one of the most popular lecturers of the 1970s visiting colleges.

Jean Kilbourne: Well, there was one point somewhere in the early '80s that The New York Times Magazine said that I was one of the three most popular lecturers on college campuses. One of whom was Maya Angelou, so I was very pleased by that. We actually had the same agent.

But I was, in the very beginning, doing maybe 110 lectures a year. I was going out on Monday and coming back on Friday, a different place every single night. I think I've lectured at close to half of all the colleges in the US and most of the ones in Canada. I also traveled a lot in Canada. So I've been on at least 1500 campuses. I was out just on the road all the time. I was young, so it was exciting, and it was exciting to see audiences' reactions all across the country. I've lectured in every state, every province. Then I had a child fairly late in life and cut back, but I still was doing like 70 a year, but I didn't want to be away from home more than about two nights a week. So that's how I managed that.

Andrew Mitrak: Is this partly what inspired you to turn your lecture into a film? Just that this travel schedule was so intense and there's clearly such demand to see your lecture? Is this what inspired the film version of "Killing Us Softly"?

Jean Kilbourne: That would make sense, but that's not what happened. In those days, I still didn't have very high self-esteem, and it never would have occurred to me that people would have wanted to turn my lecture into a film. That just wouldn't have crossed my mind. So two filmmakers approached me and said that they wanted to turn it into a film. My reaction was, "Oh my, these nice filmmakers think that my work is important." Looking back, this is kind of crazy, but that's the way it was, not just for me, for a lot of women. So the film was made. It was a one-take, one-camera film, cost $6,000 to make, and it, in today's terms, went viral and made a lot of money and also was seen by a whole lot of people. Unfortunately, I had made a very bad deal with those filmmakers, so eventually, I switched over to the Media Education Foundation and have made my films with them ever since, and that's been much better for me and for everybody.

The Viral Spread of “Killing Us Softly”

Andrew Mitrak: Do you have a sense of how it went viral? Where were people actually watching it? Where was it being played?

Jean Kilbourne: I have no idea except word of mouth. It was shown in classrooms. I think in particular, feminists who were teaching found this an incredibly effective way to teach their students about sexism in an entertaining way, in a way that would capture their attention. I think it just had to be word of mouth, people at conferences, people at different places. Of course, the fact that I was on the road and I was spreading the word that way. But when I think about it, I could be on the road for 100 years and I wouldn’t reach nearly the audience that “Killing Us Softly” has been able to reach. It just happened due to word of mouth because in those days there was no social media. There really wasn’t any advertising to the film.

Andrew Mitrak: Did it going viral change your career at all?

Jean Kilbourne: It changed my career a lot in two ways. One is, not so much about my career, but in terms of what I was trying to do because I’ve always been an advocate, an activist. That’s really what this is about. I was able to get the messages out to so many people than no matter how many lectures I did. But the other thing is that more people saw the film, the more they wanted to see me in person. So I became more popular as a lecturer.

Andrew Mitrak: Did you come up with new materials because people had already seen the film? Did you feel some pressure, almost like a stand-up comedian, once their specials out they usually come up with new material. Did you think, “They’ve already seen the film so I need to have new ads or new materials?”

Jean Kilbourne: The trouble is the ads turn over so fast and there was no way I was going to be able to keep up. Some of the ads were so perfect and making my point that I didn;t want to stop using them. What I did was I found new ads, and I would sprinkle them in, but I didn’t totally change the presentation. Eventually, by the time I got to “Killing Us Softly 3” and “Killing Us Softly 4”, I began to present them more as a historical perspective. Here’s what it was like and here’s what it’s like now. So that way, I was able to use a lot of the same material but have it updated enough to keep people’s interest. There are teachers who have probably seen “Killing Us Softly” hundreds of times and they could sing along with me at any presentation. They seem not to mind, which was very often touching.

The Advertising Industry’s Response

Andrew Mitrak: We haven’t talked about the advertising industry’s response to your work yet. What was their initial reaction to it?

Jean Kilbourne: The initial reaction was just to ignore it. Sometimes they attacked it, but not so much when I was talking about the image of women. It was when I started talking and making films about alcohol advertising and tobacco advertising. That’s when they became upset, and that’s when they started labeling me as a prohibitionist. They called me Carry Nation. They tried to turn my message into something that it wasn’t at all. Because the image of women, by that time, everybody knew it was a problem, it was going to be hard for them to fight back against that. But they could fight back against what I was saying about alcohol and tobacco. I think what I was saying about alcohol and tobacco was because I started doing research and talking about those issues in the 70s. I was presenting something very different than had been presented before.

For example, with smoking, the typical approach for kids was to show them diseased lungs and things like that. I started smoking when I was 13. I wouldn’t have cared about a diseased lung at all. I didn’t expect to live beyond 50. But what would have gotten my attention was being told that I was being manipulated by a very powerful industry that wanted my money. And that is what I did. I started talking about the ways in which these industries were targeting kids and the messages that they were using, not at all about the health consequences. Because most kids feel they’re immortal, and they really don’t care about the health consequences, but they really don’t want to be manipulated. That was my great insight on those and since then, that became the primary prevention tool working with alcohol and tobacco, but it really wasn;t then until 70s.

Is it Possible to Establish a Causal Relationship Between Ads and Harm?

Andrew Mitrak: In one of your articles, you wrote, “It is virtually impossible to measure the influence of advertising on a culture.” I’m wondering if there have been attempts to establish a direct causal relationship between advertising and some negative effects we’ve been talking about, because it does strike me that there are a lot of correlations. Is there any research that you found compelling that tries to show the exact like direct cause between these two or to quantify the negative impact, because it is clearly very tough to do. I’m just wondering if you see any kind of direct causal effect?

Jean Kilbourne: People have done studies of the influence of “Killing Us Softly” on audiences. Sometimes they found that there’s a slightly positive influence but again who knows really? I think the fact that there isn’t a control group makes it almost impossible to do the gold standard research. Some of it has been ridiculous, like I remember doing an interview with a TV person about alcohol advertising and about the effect that alcohol advertising has on us and young people in particular. Then the rebuttal was that a reporter went into a bar and asked people if they were drinking because of the alcohol advertising. How many people said yes, do you think? None. Obviously, I mean it was so stupid but that was sort of the approach because it actually is very difficult to find out. I think advertisers would love to know.

Andrew Mitrak: What is kind of ironic about the setup of the question is that advertisers want to know the impact of their ads to be able to show ROI. Whether you’re an in-house marketing team and you’re showing impact to your boss and your finance team that advertising is positive ROI. Advertising agencies, they want to show that their work causes impact. But in the same way that you would like to show “I would also like to directly measure the harm.” It’s tough to show the causality even though both of you want in some way.

Jean Kilbourne: I mean, it’s very tough, right? As you said, when advertisers try to see if this particular ad is effective, that’s hard. It’s hard for them to really measure that. At least it always has been. So maybe there’s some new technology now, but I am not aware of it.

Advice for Practicing Ethics Marketing

Andrew Mitrak: I'm a marketing professional. I primarily work in B2B software marketing, so I don't think you show so much B2B software in your slides. But I think just as somebody who is also a student, professor, or educator, just reflecting on folks who are marketing practitioners, what are some of the top lessons they can take away to help pursue their work in a responsible way?

Jean Kilbourne: One of the things that's really impressed me is how many advertisers and marketers have asked me that question. And students who are studying advertising, although I do remember one young woman who approached me and said, "I saw your film last year and I switched my major from advertising to social work." And I said, "I'm really sorry about the pay cut, but good for you." I'm obviously not trying to have people do that. But what I do ask them to do is to think about some of the ethical issues that will come up—to think about those issues before they have mortgages, before they are in a situation where they feel like they have to do it. If somebody comes along and says, "We're marketing a cigarette to women by playing on their fear of gaining weight," be in a position where you can say, "I won't do that," as opposed to feeling like you have to.

And that's one reason I think that there should be much more discussion about ethics in business schools and in classes that are talking about this, because it certainly is possible to do ethical marketing. But sometimes people have to learn more about how to do that and what to avoid. So that's one thing that I suggest. I also suggest to people that they form alliances. If they're in an agency or something, form alliances with other people who care about these issues and want to market in a more responsible way. One organization I love, and I think it may have started 10 years ago, even longer, is called The 3% Movement. Kat Gordon, the woman who started that, it started because at that time, 3% of creative directors in agencies were female. 3%. Now I think it's soared to like 11%, but in any event, most of the power was in the hands of men. And so what Kat did was she started this organization—and I remember I spoke at the first conference, and it was quite a while ago—and it's really taken off, of trying to get women and men who care about these issues to get together because there's strength in numbers. You might not want to be alone in opposing a marketing idea, but if you have people behind you, that can make a very big difference. So those are some of the things that I've suggested. I also, of course, suggest that people work for nonprofits, but again, sorry about the pay cut. I do suggest that people use their skills—because there are some incredible skills that are involved in this—use them in so far as possible in a way that helps and does not harm.

Andrew Mitrak: I think it's useful for folks who do work in this industry. Somebody's probably going to do this, and I think you want folks who are educated and mindful about this to be there because otherwise, if they all leave and all go to nonprofits, it's just the people who don't care at all who are continuing to work in the for-profit sector.

Jean Kilbourne: But people who could do it in the for-profit sector and maybe do pro bono work, which a lot of people do, for the nonprofit sector. Because God knows the nonprofit sector needs those skills. It needs good marketing and good advertising. It's really important.

Where Do Harmful Advertising Practices Come From?

Andrew Mitrak: Everything that's being discussed, I never learned as a marketer. I've read a lot of advertising books and marketing books, and nobody ever told me, "Here's how you Photoshop somebody to look unnaturally skinny and perfect. And here's how you manipulate people and here's how you lean into their desire and unfulfilled needs." You don't learn that.

You learn things like how your product is positioned and what your segment and target audience are. Where do you think these underlying things come from? Is it just an unspoken pressure that the industry has to Photoshop people in strange ways? Where are these ideas coming from if they're not in marketing textbooks or advertising books, and they don't speak about it publicly in conferences? But it does happen and it does come out in the open. Where do you think it originates?

Jean Kilbourne: That's an excellent question. I really don't know because you're absolutely right. It's not in textbooks, it's not in conferences. And I'm not a conspiracy theorist. I don't think that it's taking place in dark rooms somewhere—well, it is taking place in dark rooms, never mind. But it must be in photography studios and advertising agencies. There must be, because obviously people are doing this, they're doing it all the time. So somebody's teaching them; they're learning somewhere. Where do you think?

Andrew Mitrak: A hypothesis I have is that if I just look at artwork in general, I remember seeing Michelangelo's David in Florence. Perfect body. I don't have that body. This sculpture is more than 500 years old now, and there is a lot of artwork that shows ideal forms of people. Also, when I was doing filmmaking and learned to color-correct people, you know, the lighting's off, let me adjust that. You kind of give people a tan a little bit with your color grading. I don't think I was intentionally trying to say, "Oh, tan skin is beautiful," but we're primed this way through artwork, through advertising, through all sorts of media we consume of what looks good. And we do that. And people, maybe not even consciously, just have an intuition around what are good aesthetics. In some ads, it might be an unconscious bias somebody has to just create beauty or fix what they see as some blemish or flaw. It might not even be that conscious. The work you're doing is actually showing unconscious biases that have compounded to create these distorted aesthetics that we see in advertising. That's just a hypothesis or a musing that I had.

Jean Kilbourne: I think that's part of it. When you mentioned the statue of David, an ideal image of beauty has existed forever, probably. But the difference between seeing a statue of David and being hit with an ideal image thousands of times a day everywhere is a very, very different thing from appreciating the beauty of a figure in an artwork versus not only seeing it everywhere but seeing no other options. Almost always, for women and for men, the models are very, very specific.

The other thing is, what a difference… every time I go to the museum and I see, you know, Rubens for example, and I see the women, I think, how would this change women's lives if this were the ideal? I think it would change women's lives dramatically. So that says something about the power of the image. And in terms of people doing this unconsciously, I think you're right. I think that sometimes does happen. But I also think if they're selling a diet product, they're going to do whatever they can to make the person look as thin as possible, including ridiculous things where the thinness becomes so incredible and so extreme that it's absolutely impossible. The person is a skeleton.

Andrew Mitrak: I recall some of the images in your lecture series, and I think you even used an example of a model, I think from South America, where she died at like 88 pounds from anorexia and probably felt tremendous pressure. So really, some very awful, "killing us softly," negative consequences from that.

Jean Kilbourne: Right. Yeah, a lot of anorexia, a lot of eating disorders. And not all the models, obviously, but the models, most of them have a certain type of body. It's very tall, very thin, usually not very full-breasted, so that's either done through Photoshop or implants. But it is a very specific body type, and I always say, there's nothing wrong with this body type at all, but it's a body type that basically 5% of American women have. So if that's all you see, then you begin to feel… and you can't diet yourself into this body type. You just can't. Most women are more apple-shaped than V-shaped.

Learn More About Jean Kilbourne’s Work

Andrew Mitrak: Jean Kilbourne, thanks so much for this conversation and for your work and for sharing your insights and wisdom and reflections with us. This has been great. For folks who have enjoyed this conversation and want to learn more about your work, where would you direct them?

Jean Kilbourne: I think probably to my website, if that isn't too old-fashioned. Because that's where people can find out about my films and my books. I have a couple of books and many articles, and I also have a resource list where people can get further information. It's a resource list where I talk about parenting resources and media literacy and all kinds of different resources. So I am on LinkedIn and stuff, but probably going to the website is the best way.

Andrew Mitrak: Well, yeah, I'll paste a link to that in the show notes and the blog that accompanies this post. Jean Kilbourne, thanks so much. I really enjoyed this conversation.

Jean Kilbourne: Thank you, I enjoyed it too, and thanks for such great questions.