A History of Marketing / Episode 31

Last time on A History of Marketing, Paul Feldwick celebrated advertising’s roots in entertainment and spectacle. This week, we hear almost the opposite perspective.

My guest, Robert J. Herbold, spent decades leading marketing at Procter & Gamble and then served as Chief Operating Officer at Microsoft. From the client side, Bob values discipline and persuasiveness above all else. He even calls advertising creative that strays from strategy “gobbledygook.”

The contrast highlights why marketing is such a rich topic to explore, and I think there’s something to be learned from both. As Rory Sutherland writes in Alchemy, “The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.”

Bob’s career illustrates that tension on a global scale. He spent 26 years at Procter & Gamble, he worked inside the legendary brand manager system that became the blueprint for modern consumer marketing.

P&G is among the most talked about companies on this podcast, second only to Coca-Cola. Bob shares an inside perspective on what brand management means at the company, and shares lessons from leading P&G’s global marketing and market research functions.

As COO of Microsoft from 1994 to 2001, Bob reported directly to Bill Gates during a period of unbelievable transformation. During his tenure, he helped navigate:

The “Start Me Up” launch of Windows 95, which was the first consumer marketing campaign of its kind for a software product

The $150 million investment that saved Apple from bankruptcy.

The "browser wars" with Netscape and the U.S. government antitrust case that followed

The CEO transition from Bill Gates to Steve Ballmer.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

This also felt like a special conversation to me. While I’ve never worked directly for Microsoft, I live in Seattle, and several of the best bosses I’ve had are Microsoft veterans. In speaking with Bob, his perspective on marketing reminded me of things I learned from them.

So this is a great conversation about leadership, discipline, persuasion, and the inside story of marketing at two of the world’s most influential companies.

Bob Herbold's books discussed in this episode:

What's Holding You Back?: 10 Bold Steps that Define Gutsy Leaders

Seduced by Success: How the Best Companies Survive the 9 Traps of Winning

The Fiefdom Syndrome: The Turf Battles That Undermine Careers and Companies

Special Thanks:

Thank you to Xiaoying Feng, a Marketing Ph.D. Candidate at Syracuse, who volunteers to review and edit transcripts for accuracy and clarity.

And thank you to Bill Moult, whom you may remember from episode 23 of this podcast, for introducing me to Bob Herbold.

From Computer Science PhD to Marketing CPG

Andrew Mitrak: Robert J. Herbold, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Bob Herbold: Thank you.

Andrew Mitrak: I'm looking forward to a conversation about the lessons and insights from your career. I thought I would start at the beginning by asking you this: How does a guy with a PhD in computer science find himself in charge of worldwide marketing and brand management for Procter & Gamble?

Bob Herbold: I chose Procter & Gamble because it was a very strong company. They have a lot of technical expertise, much deeper than people would imagine, given the businesses that they're in. What people don't understand is marketing at Procter & Gamble is extremely quantitative. They have a world-class market research organization that collects data reliably on how consumers react to your product and the competitor's product. Consequently, it's a lot of statistical analysis, and it's great fun. Basically, you're learning the ropes in terms of brand management, what it takes for a brand to be profitable at Procter & Gamble, and what the components of profitability are, et cetera—and of marketing.

Things moved quickly. After about five years, I was put in charge of the brand management organization—the advertising group. Then I became the VP of Market Research. They needed somebody with a lot of computing skills as well as statistical skills because it was time to move the market research organization into the current technology that was being used in that industry. And so, I became the Senior Vice President of all of those areas that we've just talked about: marketing, market research, and information technology.

The Call from Bill Gates: Leaving P&G for Microsoft

Bob Herbold: I was on year four when I got a visitor that represented Bill Gates. They explained the job at Microsoft, which was the Chief Operating Officer. I said, “Well, it sounds like a fine job, except I'm not leaving Procter & Gamble because this is a great company. I'm doing well, things are rosy, and why should I leave?”

So, they said, “Well, just go visit with Bill for a day, and then let's see what you think.” So I went to visit with Bill for a day. We hit it off. He wanted me to come back the next week, and that's when it was time to make a decision: Either I was going to get serious about this, or I'm not. I made the nervy move of deciding to leave Procter & Gamble, which is a rare thing for somebody at the level I was situated at. So I went to Microsoft in late '94 and was the COO until 2001, when I retired.

So that's really a strange set of steps. On the other hand, the thing that is common as you go from one to the other is that in each case, the company was basically taking advantage of an opportunity for somebody that seemed to be able to deal with a variety of situations, which I was able to do. And I enjoyed every one of it. So that's the long answer to your short question.

Andrew Mitrak: I'm sure we'll jump around a little bit in this interview, but I want to ask you about Bill Gates and Microsoft because one of the things that's astonishing to me is that in 1994, I think Bill Gates would have been in his late 30s, like 38 or 39 years old. Not a lot of people left Procter & Gamble; you'd spent 26 years there at that point. So what was it about Bill Gates, Microsoft, or the opportunity that drove you to leave?

Bob Herbold: It was the technology. Simply put, I was a nerd at heart in terms of really enjoying the technology. The decision to go there was really twofold. One was the lure of working with the technology again. Secondly, it was the quality of the people I met at Microsoft that Bill exposed me to during those two days.

I was very skeptical of Microsoft in terms of talent. You need to understand, Procter & Gamble does a superb job at personnel management. They're very careful with recruiting. They know who they want; they know the skills they want. I was so surprised to find out that basically, it looked like Microsoft had the same kind of principles. Those two things were the lure, but when you boil it all down, basically my family—my wife, one of our kids—said to me, “I don't know why you're worrying about making this decision. It's pretty obvious. When you get to be 65 years old, you can say, ‘Well, I worked for Procter & Gamble for a jillion years, and it was total fun.’ Or you can say, ‘I worked for Procter & Gamble for 26 years, and you just went and did this fun thing.’ So you take your choice.” And so I decided to take the leap and to go over to Redmond, Washington, and enjoy the industry and the people at Microsoft.

What Bill Gates Saw in a P&G Executive

Andrew Mitrak: What do you think Bill Gates saw in you? I'm sure they could have seen a lot of different COOs and hired a lot of different people. Why did they single you out, and why do you think they hired you?

Bob Herbold: Well, first of all, my responsibilities at Microsoft were basically the business components. I had finance, information technology, human resources, manufacturing, marketing, and market research. Basically, Bill ran the product groups, and Steve Ballmer ran sales. So I had the rest of it.

What Bill saw in me was somebody who's got a heck of a lot of battle scars from many directions. So this seems to be a guy that he's not bothered by throwing all kinds of different problems at him and just working to fix them. At Microsoft at that time, we were a fairly fat organization. We had hired too many people. The systems aspect was a mess. There was a lot of opportunity to improve the profit margins by getting the costs under control. That was one of my big jobs, and several major transitions needed to be made.

Learning Marketing by Doing: The P&G Brand Management Model

Andrew Mitrak: I want to ask you about some of your battle scars at Procter & Gamble. You had to learn marketing once you were there because you became in charge of a marketing group with a technical background. For listeners who might not be aware, Procter & Gamble's marketing and brand management function is legendary. On one of the first episodes of this podcast, we talked about the history of Procter & Gamble and Neil McElroy, who started their brand management model in the 1930s. I'm wondering if McElroy's legacy came up during your time at Procter & Gamble or if they had a marketing training function or a brand man training function for people encountering marketing from a technical background like yourself.

Bob Herbold: Marketing at Procter & Gamble is taught by doing it. You listen to your brand manager and your assistant brand managers on the brand group, and as a group of five or six people, make your product great. I don't want to pooh-pooh marketing, but it's a very easy discipline to pick up. By that, I mean if you care about the consumer—if you care about who's buying your product and why—that's marketing, okay? Brand management at Procter & Gamble teaches you a very good lesson about marketing. Marketing isn't worth a hoot unless you're making some money, okay?

Brand management is all about you having responsibility for coordinating a product development group assigned to your brand. That product development group doesn't report to you, but they are focused only on—that small group is focused only on your brand. You have to manage that relationship so you can go to them and say, “We need to improve this aspect of our product,” and consequently, let’s work on that. You have a couple of finance people assigned to your brand. Once again, they don't work for you, but you have this relationship where you go to them in terms of how much money we are making, how we are allocating our costs, etc. Same with manufacturing. There are a few people you work with to get your product made. You're putting together volume estimates for the months to come to figure out how much to make. You're working on the advertising itself, be it print or TV. You're working on the finances to make sure this thing is going to make sense. You're working on product development to improve your products in the future. That's the core of Procter & Gamble brand management.

P&G’s Three-Sentence Brand Strategy

Bob Herbold: When people say, “I worked in advertising or marketing at Procter & Gamble,” they're really not serious, okay? What they worked in was brand management. You learn a lot about bad marketing by understanding your product and your profitability. Your tendency to buy stupid advertising from the advertising agency is much lower than the average company because you probably don't have any respect for the gobbledygook they're going to put in front of you if that's what they're doing. You're very willing to call a spade a spade when they've gone overboard on creativity and have underwhelmed you in terms of persuading the consumer to take an interest in your product.

Advertising at Procter & Gamble for a brand group is getting persuasive advertising from the agency that's going to actually sell your product. There's a lot of discipline in that task. One is the strategy statement. You hear people working on strategy, and they hire fancy consulting companies. They build binders of gook that they think represents their strategy. Strategy at Procter & Gamble: three sentences, okay?

The first sentence for your brand is the benefit you provide the consumer. For example, in the case of Tide, you're the superior detergent. That means you're going to beat on product development to always have products that outperform your competitor in a blind test, and that's where the product should be. In the case of Tide, that's where it lives; that's where it's lived for many years. The same way with Crest in terms of cavity protection, et cetera.

That second sentence is the reason why someone could believe the benefit statement. You get the reasons why the product can deliver. Sometimes that's an on-air demonstration, I should say, and sometimes it's something else.

The third aspect, that third sentence that's important, is the character statement, which is: If this brand were a person and they walked in the door, tell me about them. In the case of Tide, it's a trusted member of your family that you rely on to make sure you never have a doubt that you're getting the best cleaning possible, that all the stains are out that can, in fact, be taken out.

Consequently, simplicity was key. One of the things you learn at Procter & Gamble is that business is not that complicated. People make it complicated. They mess things up because they overthink the whole deal. Consequently, you get a lot of bad marketing, products that don't deliver, etc. The consumer finds out very quickly. At Procter & Gamble, you're driven by the consumer, and you have a lot of good measures on your product in terms of whether it's performing. So that's the long and short of it.

Andrew Mitrak: If you think of the AIDA model of advertising—attention, interest, desire, action. An example I've used for sharing the AIDA model or explaining it to somebody who's learning marketing is a Swiffer ad, which is a Procter & Gamble product.

It might have been after your time there, but if you look at their ads for it, you can see beat-by-beat in a 30-second ad: Attention—they'll grab your attention. I think the ad was that a traditional broom just moves dirt around; it doesn't actually get rid of it. Interest—the dirt needs to be removed, not just moved. Desire—the Swiffer cloths are differentiated; they can collect dirt and be thrown away. And then their ads would end with, “And here is where you can buy it at the store, at the household cleaning aisle at your local store.” It has it all really tightly packed in there, and it's not some celebrity endorsement or doesn't have all the fluff—I think you called it gobbledygook. It's just really tight. I'm sure I could find any Procter & Gamble ad and see that it's all really tight fundamentals and really lean to get the message across.

Note from Andrew - Thanks for Ben Thompson at Stratechery who introduced me to this example of the AIDA model in action in this article: https://stratechery.com/2020/the-anti-amazon-alliance/

Bob Herbold: Yep.

Launching Liquid Tide: How P&G Innovated by Competing with Itself

Andrew Mitrak: While researching and prepping for this interview, I watched some of your lectures that are available on YouTube, and you spoke a lot about inflection points. This is probably more speaking to business leadership in general and the inflection points that companies have faced. I'm wondering, when it comes to brand management and marketing at Procter & Gamble, were there any specific inflection points that come to mind in your 26-year career there?

Bob Herbold: There were several. Probably one of the largest was when I was running the advertising, marketing, and brand management group of package soap and detergent. One of our brands was Tide. Someone had come up with a liquid version; it was all powder at that point. In R&D, they had been working for years and years on a liquid detergent that would clean as well as powder Tide.

When I was there, the product development people claimed they had finally achieved this. Naturally, we exposed those formulas to extensive product tests where basically it was liquid Tide versus powder Tide in blind tests, usage tests, and the like, as well as against the competition. Liquid competition at that point was really weak in the context of cleaning. The blind test showed that this thing cleaned as well as powder Tide. Launching that product generated a huge boost for the Tide franchise. We offered both powder and liquid for many years, just in case there were people that absolutely loved powder detergents. That was a really important inflection point in the industry—that someone could come up with a formula that would clean as well as that. That was a ton of fun to market that baby.

Andrew Mitrak: I wonder if there was a risk of perceiving this as, “Hey, we might cannibalize ourselves if we're converting people over to liquid; we might lose some of our…” But also, if you don't cannibalize yourself, somebody else might do it for you, and that would be a bigger risk, right? Is that the dilemma you were facing?

Bob Herbold: Absolutely. We knew it would cannibalize; it was the subject of how much. But also, we knew it would kill—I should say that it would beat the liquid competition, which was very weak at that point.

I don't want us to get sued by the government.

Andrew Mitrak: Exactly. I’m sure this is probably the scars of the antitrust investigation into Microsoft. You can't use "kill." Can't use those words about your competition.

Bob Herbold: You can’t use those words…

Anyway, we knew we could get business from both parties. The powder would be injured, so to speak, and we'd get a lot of new business. We ran a test market on this very issue. One of the things that's great about the consumer products industry is you can isolate an area and do a very clean test to understand the nature of the change you want to take place.

How Measuring Persuasion Changed P&G Advertising

Bob Herbold: Another inflection point that I think was very important was when I was running Market Research and we came up with a measure that was what we called a “persuasion measure.” We tested this thing nine ways from Sunday to make sure that brands that used what we measured as persuasive advertising, in fact, had a marketplace impact when they ran that advertising. We ran a lot of split-cable tests on this issue to find out that our tool for measuring persuasive advertising was really working very well. Consequently, from that point on, any new advertising had to be tested with the persuasion tool from the MRD group to understand whether this was really going to make the mark relative to the consumer. A huge inflection in terms of having some confidence that the advertising was going to work.

Now, I'll tell you the people who hated this were the ad agencies, okay? Because somebody has a report card on this advertising done at the time of the early testing of an ad. It was a great tool, and I'm assuming it's still used—the evolution of that tool. It was powerful.

Creative Ad Agencies vs. Strategic Clients

Andrew Mitrak: I'm picking up on a little bit of disdain for certain types of ad agencies or certain types of creatives. I'm wondering, did you ever butt heads with them, or did you ever have direct interactions that are memorable with your ad agencies?

Bob Herbold: Oh yeah, no doubt about it. In fact, I'll never forget when I first had responsibility for package soap and detergent. The guy who was running Compton Advertising (which became Saatch & Saatchi), which was one of our large advertisers at that point—a company that has subsequently been acquired, then acquired, and then acquired...

Andrew Mitrak: Like most ad agencies, it seems like.

Bob Herbold: This guy looked at me and said, “Oh no, I worked with Herbold three years ago, and he's dreadful to work with. Oh no, not Herbold again.” He said that to my face. I laughed and said, “Yeah, I'm here again.” That was a funny reaction. But the fact is, yeah, we gave the advertising agencies a fit at times because they would love a piece of very creative advertising, and it would fail in terms of all of our measures. Sometimes they would say, “We have to go to the wall on this one.” We'd put it in a test market, and it wouldn't work.

That's what you have to do with an ad agency. The problem with many marketing organizations in many companies is they don't have the nerve or develop the expertise to say to an ad agency, “No, we don't like that stuff. Go make some more. Go generate another creative idea.” It can be a stressful process, but if you want to win in the marketplace, you've got to go through it.

Andrew Mitrak: I know we're jumping around here, but let's jump ahead back to Microsoft, now that we've heard some of those P&G battle scars. Marketing is among the portfolio of disciplines or functions of the company that you're overseeing, but I'm curious, were there any marketing principles you were able to bring from P&G into Microsoft? This discipline of brand management and this rigor in ad testing—were you able to bring any of that over to Microsoft?

Bob Herbold: Yes, to some extent. I was compelled not to divulge, for example, the persuasion work simply because that wouldn't be appropriate. That's Procter & Gamble's entity that is very valuable and very unique to them. But on the other hand, what Microsoft needed was basics. They had no basics in terms of marketing to speak of. They were just starting to put their toe in the water on advertising.

One of the first things we did when I got there was to measure, through market research, “name a software company.” In 1994-95, if you asked that question, the name that popped up was IBM, okay? Anything dealing with a computer, the name that popped up would be IBM. Microsoft awareness was very, very low, and what Microsoft does was even more mysterious.

Building the Microsoft Brand: A Lesson in Basics

Bob Herbold: So we put about a campaign of television advertising to try and get at the fact that Microsoft is a software company. Software helps you become creative and do things that are going to be valuable to you. In fact, I brought forward the old strategy statement from Procter & Gamble in terms of what's the benefit, is there a reason why, and what's the character statement. The benefit statement was, “Microsoft software leads the way in providing access to a new world of thinking and communicating.” That's an important statement. That's what we had the ad agencies write advertising for. “Microsoft software leads the way in providing access to a new world of thinking and communicating.” All of a sudden, it gets real simple as to what the advertising should communicate. The character statement was, “We're here to help. We're a friend that can assist you and make a whole bunch of tasks a whole lot easier,”—that kind of ilk.

We developed advertising along the lines of that strategy. Wieden+Kennedy was the advertising agency. We tested the advertising extensively, and after a couple of years of running it, when you go to consumers and say, “Okay, name a software company,” Microsoft was right at the top of the list by a big, big margin, and IBM had fallen way down, which is exactly what we wanted to have happen.

Behind the Scenes of the Windows 95 Launch

Andrew Mitrak: If you joined Microsoft in late '94, I imagine the Windows 95 launch, which I think happened around midway through '95, must have been one of the first... To me, it might be the most iconic Microsoft campaign that I can think of, even though I was very young when it happened. Was it one of your initiate? I'd also read that this cost like $300 million, which was a lot of money at the time. Driving efficiency and driving profitability was another mandate you had, so I imagine it didn't come easy to spend a lot of money on a big launch like that. I'm just curious, what was your approach to this Windows 95 launch? Do you have any stories from it?

Bob Herbold: Yes, it was very significant. Bill Gates led the charge and said, “Listen, we're betting the company in moving from a 16-bit word to a 32-bit operating system. This is a huge rewrite of the operating system. We're taking a big risk with the whole company, so every aspect of the company must do their very best work,” okay?

In regard to manufacturing, we had to have the product all ready to go globally on August 24, 1995. From an advertising standpoint, we had to have great advertising. We ended up spending a lot of money on The Rolling Stones, utilizing the Start button of Microsoft, running their famous song.

Andrew Mitrak: "Start Me Up."

Bob Herbold: The budget on the whole thing was huge. On the other hand, this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But what's really interesting is toward May, June, July of 1995, there was a lot of pressure on the company and a lot of articles being written basically saying, “Microsoft missed the internet,” okay? You may not remember that, but it was brutal in terms of positioning us as completely flat-footed when it comes to these new tools that the internet can provide.

We constantly said to Bill, “What are we doing here in terms of, you know, what product group is aligned against this thing?” He said, “Listen, until the 24th of August, this company is totally focused on Windows 95. Once that occurs, we'll go from there.” People ignored the internet while we polished all the stuff related to the launch of Windows 95, which we pulled off successfully. It was televised throughout the world with a big event we had on campus with Jay Leno—a major kickoff.

Right after the kickoff, basically, Bill organized the troops and focused on the internet. Within a very short period of time, we had the initial versions of Internet Explorer out there, battling with Netscape. For the next year or two, it was all about Windows 95 penetration and getting Internet Explorer's market share up and putting it on the map. So Windows 95 was very, very important, but I really learned a major lesson on focus. Bill did the right thing by totally focusing the company on that very important project.

High-Interest vs. Low-Interest Categories: Tech vs. CPG

Andrew Mitrak: It just strikes me that the "Start Me Up" licensing from the Rolling Stones, the big splash with Jay Leno, who was just the new host of The Tonight Show—those types of things don't feel like Procter & Gamble. They don't seem like things that Procter & Gamble would do for marketing. What was your perspective as somebody who spent your whole career at Procter & Gamble and is now doing the types of marketing launches and tactics that you wouldn't have necessarily done at your prior company? What was that like for you? What was your assessment of it?

Bob Herbold: It wasn't as different from Procter & Gamble as you would think. For example, if you looked at what we did behind liquid Tide, the amount of money that was spent and the overall effort through our sales organization to get the retail trade excited about pushing this new product was huge. Now, one of the differences between the two, with the Tide experience versus the Windows 95 experience, is that detergents are a low-interest category, okay? Technology is a high-interest category.

What you're going to have is media getting all interested in technology because it's very G-Whiz, and it affects people very, very directly if it gets to the point where people think it will get. Detergents are a completely different issue, okay? You're going to affect people who shop for groceries, you're going to affect people who do the laundry, and so the target audience is much narrower, much quieter, and the whole thing is very different. But in terms of the importance that you treat the project and how it is executed, you wouldn't see as much difference as you think.

People often say to me, “Man, that was a massive change between Procter & Gamble and then going to Microsoft. What in the world?” I said it was very interesting because there are some aspects that didn't change at all. Both companies hire really, really good people, and they take the time to make sure that they're really smart and that they're really qualified to do the job. Consequently, with both companies, you're working with really good people. The second thing that was so similar is the focus is on the product. You really get that at Procter & Gamble, and I was so surprised to feel the same thing at Microsoft.

Then it changes dramatically. The speed of the industry—it took years of chemists and chemical engineers working on those liquids to figure out how in the world they were going to match the performance of the powder detergents where they can basically deliver the key ingredients to a garment in such an efficient manner. At Microsoft, or in the tech industry, things move so fast. The speed of the underlying industry is gigantic. I often tell people it takes much, much longer to develop a formula that will take a Merlot wine stain out of a white shirt compared to doubling the capacity of a microprocessor. The difference in industry was key, but you quickly learn the necessity of not being quite as careful as you would be at Procter & Gamble, but you've got to get on with things, and you do them as carefully as you can. But speed's important in that technology world.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, the world of atoms versus the world of bits.

House of Brands vs. Branded House: Comparing P&G and Microsoft

Andrew Mitrak: The first thing you mentioned when you were coming to Microsoft was unaided awareness of software companies and how people would come up with IBM, and Microsoft was pretty low ranking. But you had to market a lot of brands, right? You had to market Microsoft, but then Windows, and then Excel versus Lotus 1-2-3, and Word versus WordPerfect, and you mentioned Internet Explorer versus Netscape. So you're marketing a lot of stuff at Microsoft. How did you think about that? When it comes to, you mentioned the importance of focus and landing Windows 95, but within Windows 95, there are all these subcategories of brands that are also being marketed together. As the COO who was in charge of marketing among other things, how did you balance all of those brands?

Bob Herbold: Well, to be clear, each of the products—like Microsoft Exchange or Microsoft Office—have a very significant marketing group within them, okay? They're the ones that are actually responsible for developing the ad. On the other hand, the corporate advertising and things that are going to go broad, we had a hand in. So consequently, a piece of advertising like "Start Me Up," we provided a lot of the funds, they provided a lot of the people to do the selection of the approach and the like. We sat in on all those meetings and the like.

We had an oversight role and were very involved on those big projects, but on an ongoing basis, in terms of materials for sales and standard kinds of marketing things that are very important, the product groups handled a lot of that as well. So the relationship between marketing efforts centrally and in the divisions was very active and important so that they knew how to represent Microsoft with the same kind of face across all those divisions. That's another thing that's important when you have many products like that—and this is quite different than Procter & Gamble—is that you actually have one brand, and that's Microsoft, and then you have a lot of sub-brands, et cetera.

That's not the case at all at Procter & Gamble. At the time I was there, and until very recently, you never mentioned Procter & Gamble in a brand's advertising. So at Crest or Sure deodorant or some of the other products, you'd never hear the Procter & Gamble name. You would only hear Crest, or you would hear Tide or Sure or Cheer detergent, et cetera. So, a very different approach globally.

Andrew Mitrak: Is one approach better than the other, or is it just more like a cultural marketing thing?

Bob Herbold: I think in the technology industry, it's much more focused on big brands that basically can leverage the names. I mean, IBM had many, many different products, but basically, you were buying IBM. So, a similar analogy. Hewlett-Packard, the same case. The name Hewlett-Packard, be it a server or a PC or whatever, represents a quality level that you come to understand.

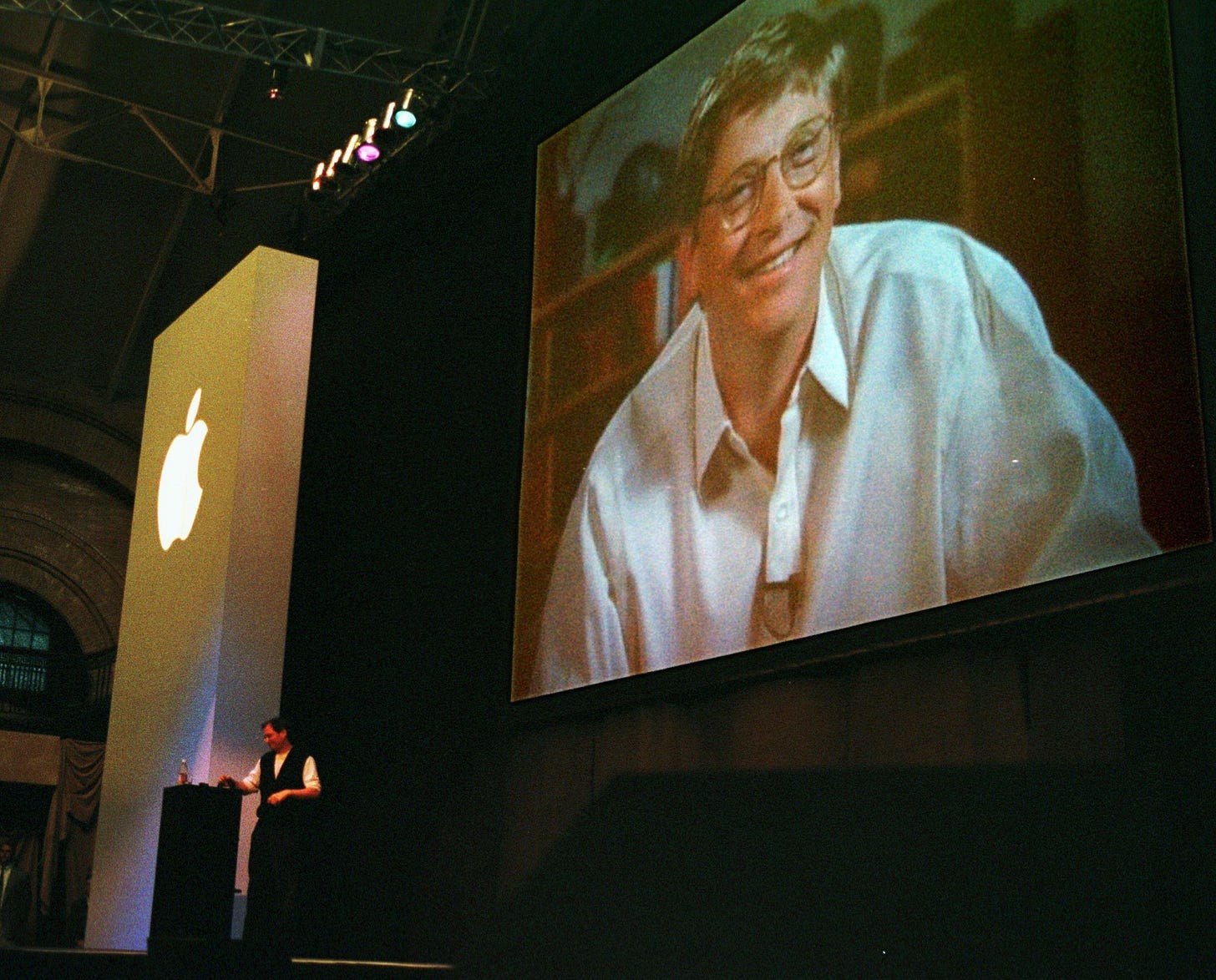

The Story Behind Microsoft's Investment in Apple

Andrew Mitrak: One moment that I wanted to ask about is that you were at Microsoft at the time that Microsoft invested $150 million in Apple, which was right on the verge of bankruptcy. There's also this very famous video of Bill Gates appearing on video at the Macworld conference, and Steve Jobs seems small—he's standing there physically behind a podium, and Bill Gates's giant face is behind him. It's just one of these—the perception is so funny because they're such two iconic individuals within tech and within marketing. I'm wondering if you remember this period and any stories you're able to share of this Microsoft investment in Apple.

Bob Herbold: There were some meetings between Bill and Steve Jobs where Jobs would get off target. Jobs was always hung up on the fact that he would complain to Gates that Bill should feel guilty selling Windows because it was an expletive deleted, okay? It was a piece of blank, big time. So consequently, him having to come to Microsoft while he served up Bill... Bill was a good friend of Steve, but on the other hand, they were fierce competitors. That was a humbling situation where he had to come. We wanted Apple to succeed because it's always good to have a competitor.

We ended up giving them the money, but subsequently, they asked him to appear in front of their analyst meeting a couple of days later, once we agreed. That led to the incident that you're talking about, where people remember the "1984" ad, or whatever it was, with the woman running down the aisle, swinging the hammer, and crushing the big dude that was on the screen. That guy represented the status quo and the bureaucracy, et cetera. So when Bill did appear, suddenly Steve knew the mistake he made. Right after that event, we understand—can't verify this, but we understand—that most of their PR department was fired simply because they put him in such a funny position. Because the audience was laughing because of what he had created, which was, you know, the bureaucracy won. The status quo is in charge, and there he is on the screen giving us money in order to survive. So it was hilarious.

Product vs. Sales: Assessing Gates and Ballmer as Marketers

Andrew Mitrak: So you came in, there was Bill Gates at the time, CEO, in charge of product, and there's Steve Ballmer, who's in charge of sales, and then you're in charge of everything else. And those wind up being the, you know, Bill Gates was CEO from Microsoft's founding through around 2000-2001, and then Ballmer was the CEO after for the next 10 years or so. I'm just wondering if you have an evaluation of the two of them as marketers.

Bob Herbold: Steve Ballmer was very involved with marketing and consequently worked very closely with the people in marketing because he cared a lot about it, and appropriately so. Bill was not as interested, okay? He's a product guy, primarily, extremely good at working with product development and the like. So, those two individuals were quite different.

When Steve took over, you wouldn't want to say he's not a product guy, but we got somewhat seduced into trying to put Windows everywhere as an operating system. When Steve tried to do that with a smartphone, it simply made a very clunky device, so it failed in the marketplace. But Bill was very good at marketing, but Steve was very good as well. Steve didn't have the product instincts that Bill did. I'm not saying that negatively. So there you have it.

How to Learn Marketing? By Doing It.

Andrew Mitrak: I want to also ask about education because you've spent a lot of your career focused on education. We talked about you earning a PhD, but you were on the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, and you were also focused on K-through-12 education. You've donated very charitably to education, to colleges, and endowed professors. And then you also mentioned, though, that the only way to learn marketing is to do it. So, do you have any thoughts on how we educate marketers or what people can do to become better marketers? A lot of academics listen to this podcast, marketing academics do, as well as practitioners. I'm just wondering if you have any thoughts on how to get a marketing education.

Bob Herbold: Actually, I think that the most important thing is the variety of experiences and capabilities that the individual has, not so much deep marketing skills. I remember one time, I was basically the head of marketing at Procter & Gamble, and we had a person that we really wanted to hire. They asked me to talk with him, and I did. I got the strangest question. He said, “You know, one thing I worry about, I went to such-and-such a highfalutin school here, and I only had three different marketing courses, and I think coming to Procter & Gamble, I'm going to get killed because I don't have the marketing depth.”

I said, “Well, take a guess at how many marketing courses I've ever had in my life.” He said, “Oh, probably very deep.” I said, “I've never had one.” I said marketing is all about human instincts and caring about the consumer and getting the product right and common sense as to what's going to persuade people to buy this product. I said, I don't want to pooh-pooh marketing, but it's far simpler than you think. A lot of times, marketing people get too involved in trying to apply this, that, or the other thing from a textbook.

What's going to make a product successful is it's meaningful to the consumer, you have the capability to explain why it's meaningful to the consumer, and thirdly, you get them to try it. That's a marketing task as well. There are ways to do each of those things, and it's not that hard. So I think the individual—and I often get asked that question, to tell you the truth—I think the more variety of experiences people have in life is probably a very important marketing lesson as well. So, a strange answer to your question.

Andrew Mitrak: No, I think that's right, to be honest. I've learned more just from doing it...

Bob Herbold: Absolutely.

Andrew Mitrak: ...than from reading books.

That said, when I read books, it is useful to take instincts and apply frameworks to them or to somehow articulate what you're feeling and thinking, so it seems intuitive to others.

But again, having a variety of experiences is so valuable. And actually, a lot of what you're saying are things that I've also heard from my managers who used to work at Microsoft, so I wonder how much of it came on through you somehow.

Bob Herbold: [Laughs]

Final Thoughts and Gutsy Decisions

Andrew Mitrak: If listeners want to learn more about your work, or if there are any... I know you've written some books, and I can publish the links to those in the show notes that accompany this. Are there any links you would point people to online or references you would choose to send people to?

Bob Herbold: The third book that I did, I think is probably a good summary of how to be successful in terms of launching a product and managing a product and marketing a product. The name of the book is What's Holding You Back?, and it's all about gutsy decisions where, in fact, you have to face reality. In some cases, you can't get all the data that you need to make the decision, but you've got to make the decision based on your gut. Gut decisions are usually based on the success of them, on the experiences that you've had in life. So I think that is an important summary of some very basic principles that people can use day in and day out. So I would point them to that book.

Andrew Mitrak: Bob Herbold, thanks so much. I really enjoyed the conversation.

Bob Herbold: Great. Thank you.