A History of Marketing / Episode 16

Tune into any major sporting event, and corporate sponsorship saturate the screen. Colossal logos sprawl across stadium rooftops. They adorn the smallest patch on a player's jersey. From pre-game shows to post-game analysis, from breakfast cereal to beer cans, from charitable causes to gambling apps, sponsorships are inseparable from sports.

Sports and sponsorship are so interwoven, it’s easy to think it was always this way. But it’s a relatively new phenomenon. It doesn’t happen naturally either. Behind the scenes marketers, brands, teams, and athletes navigate complex sponsorship-linked marketing arrangements that aim to benefit all parties involved.

My guest is T. Bettina Cornwell, a leading expert on sports and sponsorship. She is the Philip H. Knight Chair and Head of the Department of Marketing at the University of Oregon's Lundquist College of Business.

Listen to the podcast: Spotify / Apple Podcasts / YouTube Podcasts

Professor Cornwell literally wrote the book on the subject. It's called Sponsorship in Marketing and the 3rd edition of it comes out today. I read an earlier edition to prepare for our interview, and I really enjoyed it. So, if you like our conversation, I recommend checking it out.

Our discussion was an absolute blast. We cover some of the best-known successes and revealing failures in the world of sports and sponsorship.

Now, here it is – my conversation with Bettina Cornwell.

T. Bettina Cornwell: Researching Marketing Sponsorships

Andrew Mitrak: Bettina Cornwell, welcome to A History of Marketing.

Bettina Cornwell: Thank you. This is a great idea. I love it.

Andrew Mitrak: Thanks. I'm so excited to speak with you because you've spent a lot of your career researching sponsorship-linked marketing and marketing affiliated with sports. This is a topic I find fascinating, but we haven't covered it yet on this podcast. I'm really looking forward to digging into this with you. To start, what originally drew you to this area of marketing research?

Bettina Cornwell: Yes. So I like sports and I was attending a tennis match and I met the VP of North America for Volvo. At that time they were filling their cars out in front of the match with tennis balls and having people guess how many balls were in there and things like that. But that person said to me, hey, we'd like to have a more sophisticated measurement of our sponsorship value. Our CEO said demographics of tennis players and demographics of Volvo drivers match and so we're here, but we'd like to measure it. And I'm like, yeah, great idea, I love it. So that's how I got started.

Andrew Mitrak: That's great. So, starting from that initial question of how to measure the impact of sports marketing... how did you initially connect with the folks at Volvo?

Bettina Cornwell: Happened to be in the same section talking to people. You reflected on it, here's a major corporation that is super involved with this and really it's not on the academic radar at all. Looking around, once it became salient for you, you're like, “This is everywhere, this is happening. And nobody's really paying attention to it.”

The Historical Roots of Sponsorship

Andrew Mitrak: It is everywhere. It's something many of us take for granted – that sponsorships will be part of sports – without necessarily thinking about the impact. If we ground this in history, when did the relationship between sports, sponsorship, and marketing start to merge? What are some early examples?

Bettina Cornwell: Sure. You can go very far back historically if you want to.

Andrew Mitrak: Let's go all the way back. Yeah.

Bettina Cornwell: You know, gladiators being sponsored and folks putting their name on bridges and buildings. For a very long time there was a lot of philanthropy and just giving back to community but it also had a message on it as well. Then we came into what you would call modern sponsorship where companies wanted to have an image platform of doing good, doing good things.

Then programs in sport became, you know, one of the ways, national concepts of opportunities. So I want to typically parallel my sponsorship activities with my products distribution or coverage where I'm available.

So a national company would like national exposure, global company, global exposure, regional, regional. And so you try to imagine an activity where you would be recognized in some instances and then historically very much an image of philanthropy.

The IRS said, “Wait a minute, you're getting a lot of advantage from that, that should not be a tax write off. That's actually marketing activity.” And then things started to change. So it was philanthropy, it is now a marketing platform.

Andrew Mitrak: You mentioned the IRS determined this wasn't purely charitable but a marketing activity. Around what time did that shift happen, and how did it really change how we see sponsorship?

Bettina Cornwell: If I had say key moments, one would be the rise of sponsoring through the tobacco industry. Around 1970, the tobacco industry faced restrictions on traditional advertising, like television and print. Coincidentally, they began sponsoring tennis that same year. Barred from traditional channels, they asked, "How can we still communicate with our audiences?" While you don't want to give too much credit to the tobacco industry, they were super successful in using sponsorship, and other brands noticed how well it was working.

Many people also point to the 1996 Atlanta Olympics as a watershed event for sponsorship. Coca-Cola heavily promoted the Olympics at that point, being very keen to have them in Atlanta, their headquarters city. People see that as a watershed event as well, where things started to change in terms of the relationship of sponsors to sport in their role in various ways.

Defining "Sponsorship-Linked Marketing"

Andrew Mitrak: Let's jump ahead to "sponsorship-linked marketing." This is a term you introduced in 1995. Many listeners have likely heard of "sponsorship," but the word "linked" here is key. You use this term to distinguish it from the marketing of sports. Can you elaborate on that distinction and why you prefer "sponsorship-linked marketing"?

Bettina Cornwell: The marketing of sports is one activity – selling tickets, promoting leagues, etc. Marketing via sports is another – where I'm marketing my product, my brand, my vision through a relationship with a sport property.

I needed a term to describe this phenomenon, this orchestration of various marketing activities built around a sponsorship contract that might last three, five, ten years, or even decades. So, I coined the term "sponsorship-linked marketing."

There's some discussion about using the word "partnerships." I agree that sponsor relationships often become partnerships. However, referring to the whole field as "partnerships" wasn't specific enough in my view, because so many things are partnerships – co-branding, strategic alliances, etc.

Sponsorship is quite specific in that I'm writing a contract for a relationship into the future and it's different from being another company sort of on par in terms of the activities that you'll do. This is one group that's paying financial value to another for marketing association. So I needed a term and I came up with that one.

Andrew Mitrak: Under the umbrella of sponsorship-linked marketing, what are some examples of the activities and activations that fit into this category?

Bettina Cornwell: I tend to put it into two buckets, partly for business reasons – to understand which bucket is working. The big bucket I call "leveraging." This includes everything I spend beyond the basic contract rights. I have a contract with certain entitlements, but I might do other things or spend more money to amplify the association.

A subset of that larger bucket is what's called "activation." These are often the fun things you do where you're engaging people in a two-way relationship. So, my overall leveraging could include advertising that incorporates the Olympic Rings because I now have the rights to use them. An activation, within that leveraging plan, might involve having a kiosk or a brand experience at the Olympic Village, directly engaging attendees.

So, I group it into the big bucket of leveraging the contract, and within that, a smaller, highly interactive bucket of activation designed to bring the audience closer to the brand in the context.

Case Study: Nike's Evolving Strategy

Andrew Mitrak: To ground this in an example, I thought it might be fun to use Nike as a case study. You are the Philip H. Knight Chair at the University of Oregon, so you're close to Nike's headquarters. Plus, they're such a globally recognized brand known for their connection to sport. How would you describe the evolution of their use of sponsorship-linked marketing over the years?

Bettina Cornwell: Purely objective, I would have to say they're masterful in their use of sponsoring. They're clever in the way they imagine how to draw people in and introduce things you don't expect and you're like, oh.

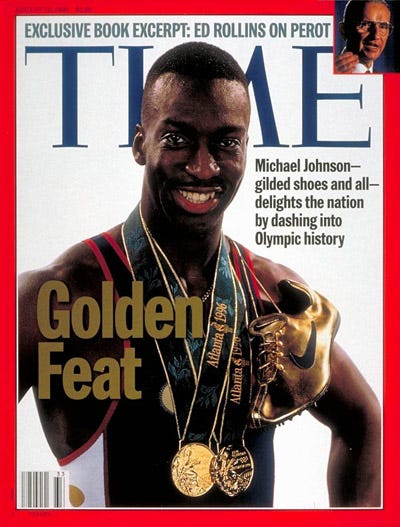

Back to that watershed Olympics in Atlanta, we had a Michael Johnson. Nike was very clever in ensuring that the photo of him that landed on Time magazine featured his gold shoes almost as prominently as his gold medal. These kinds of moments – imagining the future, anticipating what could happen, and being ready for it – are things they have consistently done well.

In terms of evolution, while they still execute those kinds of high-profile athlete moments, they've also expanded to connect more with the "athlete in everyone." Around 2012, their "Find Your Greatness" campaign encouraged everyday people to find their own greatness and connect with the brand. It was huge.

This approach democratized the relationship with sport and the brand. You still feature your well-known superstars, but you don't leave out the average person who might be buying your products.

Andrew Mitrak: Phil Knight's autobiography, Shoe Dog, is a fun read. Right from the start as Blue Ribbon Sports, he was slinging running sneakers to high school runners out of the back of his car. Then they sponsored athletes like Steve Prefontaine.

And the Michael Jordan partnership is one of the most iconic marketing sponsorships ever. The movie Air, while likely taking liberties, captured some of that story. One standout aspect of the Jordan deal was that it wasn't just a flat fee; it included incentives, royalties, and Nike stock. Is that structure common today – tying compensation to performance or product lines – or do companies like Nike typically stick to flat fees?

Bettina Cornwell: There are two questions and two branches to that. One, the performance or fee for performance, you do see that. You make it to the championship as a team sport and then you'll get additional money, so the performance part is there.

But the relationship that leads to new products and branded products by the athlete is another path of how an individual athlete or even a team can start to work with a sponsor.

Sure you see examples, some of them are not as successful. Kanye West, Yeezy and Adidas and what happened there, a lot of product involved, a lot of product on the shelves. It was the same kind of idea, but it didn't go well in the end.

Andrew Mitrak: Yeah, that went about as poorly as a sponsorship possibly could. I can see why brands might align with somewhat controversial figures – they get attention. But obviously, that can go way off the deep end, as it did with Kanye. What's the cautionary tale or lesson learned? How should brands evaluate the right level of risk tolerance when choosing who to associate their brand with?

Bettina Cornwell: That's a tough one. I think it's a worthy investigation and due diligence before you sign someone on and then make sure that their quirk aligns with your brand if they are someone who stands out and is different.

The more risk averse way to proceed is to sponsor a team or a group of people where no one individual is going to make your day.

Andrew Mitrak: Sticking with Nike for a moment, a fun, more recent example is their sponsorship of the fictional team AFC Richmond in the show Ted Lasso. It's team sponsorship, arguably less controversial – I can hardly think of a less controversial show! But it's fascinating because it's essentially television product placement masquerading as sponsorship-linked marketing, yet it looks exactly like real-world sponsorship-linked marketing. It feels meta.

Bettina Cornwell: I was about to say “It's meta!”

Andrew Mitrak: Do you have thoughts on this? Could this type of fictional sponsorship become a bigger trend?

Bettina Cornwell: People love creativity, they love things that are outside the box, but yet they still understand. And yes, I'm sure you'll see some kinds of things like that, but you can't get as much value out of exactly that if you do it the second time. It's clever, but we need a new variation, a new cleverness.

Fit, Congruence, and Authenticity

Andrew Mitrak: This relates to the idea of congruence and fit – the sense that the right brand and the right team or athlete just naturally go together. How do brands approach identifying this fit? Is it measurable, maybe using attribute checklists and matrices, or is it more intuitive, an "I know it when I see it" kind of thing?

Bettina Cornwell: Yeah, I think in a sense of back to the history, the early measurement of congruence or fit was really looking for the running shoe, running event kind of functional fit.

These days State Farm and other brands fit just fine because we're so accustomed to it. So there's been, if you will, over time, a wider acceptance of what is emic to sponsorship of sport, for example. Inside the game, inside the feeling. The same process happened with esports more recently. People said, well, you know, esports, they do these kinds of beverages, these kinds of, you know, player consoles, whatever, but they don't do anything else. Well, now they do, they have every brand you can imagine sponsoring esports.

So over time, what is congruent has really changed. And those measures are still there, there are many of them, but we've shifted over to a measure of authenticity as a good measure of how things go together. And that's that feeling you're having like this this works, this goes together. It seems authentic. And when you measure for authenticity, we have a scale. One of my previous PhD students, Aaron Charlton, and I put together the scale based on past studies of authenticity. And you can say, oh, yeah, we're authentic. We may not be running shoe running event, but this insurance company is very much related to football, right? For whatever reasons, it's it's connected.

Andrew Mitrak: That's funny. So it seems like I would have thought that the connection between insurance and sports is that a lot of people watch sports and almost everybody needs some form of insurance. If there's just enough repetition of it, you just get accustomed to it. Like, sure, State Farm is going to sponsor this or Geico is going to sponsor this because they advertise so much. But I wouldn't have expected that to be part of authenticity.

What is it that could help a brand become authentic? What are some of those specific measures that would be used to say yes, this is an authentic brand?

Bettina Cornwell: You're exactly right, repetition. If there's enough repetition and the brands are together long enough, one of the things that authenticity captures is history.

So when you get that feeling that they've been together, then the brands in their relationship become more authentic. What would have been probably in a measure of fit or congruence not very congruent, even a decade ago, is very congruent like for example for esports. Oh yeah, sure, financial services, they're there. Automobiles, they're there. Repetition.

Andrew Mitrak: So, congruence doesn't necessarily have to exist from day one. You can actually build it through sustained investment, consistency, and repetition.

Bettina Cornwell: Yes, yes, consistency and repetition. Yes.

Measuring Success: ROI, ROO, and ROP

Andrew Mitrak: This brings us back to where we started: measurement, like with Volvo. When you began looking into measuring sponsorship impact, what was the initial approach? How do you, and how does the industry, look at measuring success and ROI?

Bettina Cornwell: Well, there's how do I look at it… then how the industry looks at it.

So in the mid-80s a group called Joyce Julius began what they call advertising equivalency measurement. Advertising equivalency says essentially 30 second advertisement in this sport program is worth whatever. Then if you were to sponsor in this program and you had 30 seconds of coverage, let's say in an auto race and zoom, there goes the brand, zoom, there goes the brand. Count up those seconds.

Then the advertising equivalency for 30 seconds of exposure through sponsorship would be whatever it took to buy an ad.

Fast forward you have all kinds of new measures like that and a lot more technical sophistication. You can say, you know, it's clear and in focus, you can all kinds of companies now providing that kind of measurement. That is, however, an exposure measurement. While advertising equivalency is huge in the industry, it's a benchmark and a way of understanding return investment in the sense that you receive something that is supposedly as valuable as this ad. So I can then put it into my ROI calculation.

My problem is that we don't have more than exposure, like my purchase intention, my actual purchase and those sorts of things. And so some of the things that we've been doing for a long time are about measuring awareness or my ability to remember the sponsor if that's what they're after.

Measuring return on objectives that are important to a brand. And then, you know, brands can also do their own return on investment. And the brands that usually do a really good job at that are the brands that have receipts. The brands that know when you were there, you did this. Like financial services, if you have a credit card, you use it during the Olympics, then they know that there were people purchasing at that time, at that place.

They have a lot of information. And so some brands are really good at knowing when sponsorship is working and how it's working. Other brands have to work at it a bit more, actually sponsor primary research, have a survey, conduct research that brings together their information and sales with other information they collect from their target audience.

Andrew Mitrak: You used the word "receipts." If you're Coca-Cola or Red Bull activating at an event where people can buy the product right there, it's easier to measure that direct impact. But for longer-term purchases, like insurance or cars, where the decision isn't made right after the game, measuring ROI seems "squishier." You have to look at other indicators.

Bettina Cornwell: Yes and moreover, if you really want to know and you're one of those brands that can't find that connection, then you've got to do additional research. Unfortunately, a lot of brands don't do that in sponsoring. In fact, it's still amazing to me the number of brands that invest a very small amount of their sponsorship budget in measurement.

Andrew Mitrak: You mentioned "Return on Objective." Can you define what that means?

Bettina Cornwell: Sure. So I want to measure progress toward a goal, to measure my image. How was my image? How is my image after sponsoring? What is the awareness of my product due to the sponsorship? The potential is huge for what I would call intermediate variables, not your final goal, which may be sales.

But if you're a high-end automobile, your sale may not come for a month or 10 or 20. So knowing that you've got people interested in the product and they're investigating is sort of this interim step that you'd like to have and know that sponsorship is helping you develop that.

Andrew Mitrak: So, these objectives aren't purely financial; they can be tangential, like associating the brand with certain values. One increasingly important value is sustainability. I know you've done work on sustainability in sponsorship-linked marketing. How are those coming together? Are there examples?

Bettina Cornwell: Yes, some people are now referring to this area as "Return on Purpose" (ROP).

Andrew Mitrak: Okay.

Bettina Cornwell: They're trying to identify their corporate mission and purpose is in part maybe sustainable. And then how can they measure the movement toward that sustainable behavior? Well, with this activity and sponsorship, we also plant this number of trees or, you know, something like that. And but more fully to sort of communicate the idea that we're trying to be sustainable. We may not be there yet, but we want to do that.

An interesting example is the Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle.

The Climate Pledge Arena has now been awarded as the first net-zero carbon arena in the world. So that gives us a worldwide standard, which is amazing.

Then you understand that the the back story is then this is sponsored by Amazon and you don't know what is in Jeff Bezos' heart, if it's really about sustainability or if it's about image because some people have critiqued it as being greenwashing. But we don't know what he had in mind.

We know that he had a discussion that led him to doing this in the sense that employees actually wanted more sustainability.

But the fact is, it is an arena that the world can look at and say, wow, look what they have done. It sets a standard that other people can turn to. So sponsorship can be amazing in moving the needle in creative and different ways and I would put Climate Pledge Arena in that bucket.

Andrew Mitrak: As someone based in Seattle, I can say it's a beautiful arena. I've seen concerts and games there. It is amazing. And it's interesting – I don't think it would have the same positive reception if it were called the "Amazon Arena." Even with the same sustainable features, branding it directly as Amazon might have been polarizing. The city seems genuinely proud of the "Climate Pledge Arena" name.

Bettina Cornwell: I couldn't agree with you more and it's just an amazing example of what can be done. And I would also say that not only is the center well accepted, the arena well accepted because of its name, but it probably reflects more positively on the company because it is Climate Pledge Arena.

Debunking the "Stadium Curse"?

Andrew Mitrak: Speaking of arenas, I wanted to ask a fun question about the so-called "stadium curse." Enron Field famously existed just before Enron's collapse. FTX Arena was another recent example. There's a perception that companies naming stadiums after themselves might underperform, perhaps seen as desperate for attention or wasting money, or even destined for bankruptcy. Is there any merit to this idea? Or could the perception of a curse have a chilling effect on brands considering naming rights?

Bettina Cornwell: Nah.

But, having said that, it is the case that and we did some research on this sometime ago about the value of stadium sponsoring for brands that are not very tangible. So intangible brands, services, financial services, different kinds of things. They have a harder time seeming substantial and being known to people. So they actually get a benefit and a value for naming rights that your tangible brick-and-mortar brands don't quite get that advantage.

But then on the other hand, some of those companies can be more volatile than your than your brick-and-mortar long-standing companies. So there might be something in that, but I don't think anything's jinxed.

Andrew Mitrak: Nothing's jinxed. Okay! Well, Bettina, this has been such a fun and insightful interview. Thanks so much for your time. Where's the best place for listeners to find you online and learn more about your work?

Bettina Cornwell: Oh, that's a nice question. I have some things on YouTube. I had this moment where there were no materials to try and talk about sponsorship and so I did some videos. They're out there on my YouTube channel and they're learning glass videos. So they're curious and different. Many people have asked me about how I write backwards. I don't want to spoil it, but actually it's technologically flipped and so actually I don't write backwards.

Andrew Mitrak: For listeners, I'll definitely link to those in the blog post and show notes because they are very cool. Researching your work, I saw them and was struck by their distinctive, immersive style. You're lecturing on a transparent board, allowing us to see you explaining the concepts in a visually engaging way. It's a great way to digest the information. So, thanks for putting those out there.

Bettina Cornwell: Oh, I'm so glad you like them. Thank you. I'm also on LinkedIn, and I'm trying to build up my presence on BlueSky – I've recently moved over there. So, I'm around online.

Andrew Mitrak: Bettina, thanks so much again for joining me today. I've really enjoyed the conversation.

Bettina Cornwell: It has been my absolute genuine pleasure to talk with you and I think that you doing this is just great. It's amazing.